Prominent among the few Issei to be accepted in mainstream American culture in the years before World War II was Ken Nakazawa. Nakazawa was a well-respected professor at University of Southern California—one of the first ethnic Japanese on the faculty of an important American university—as well as a lecturer, essayist, playwright and interpreter of Japanese culture. He also served as diplomat and community leader at the Japanese consulate in Los Angeles. However, Nakazawa's outspoken support of Japan’s invasions and occupation of China ultimately eclipsed his once-prodigious popularity.

He was born in Yanagawa City, Fukushima-ken, Japan. His birthdate was variously reported as December 18, 1885 (the date on his gravestone), December 17, 1884 (recorded in government documents), 1883, and 1886, His father was Akiyoshi Goto. At some point, Ken was adopted by the Nakazawa family in Japan.

According to government investigators, he sailed to America from Yokohama in 1906 on the steamship Doric, using a passport in the name of Goto. He later claimed that all his records, including his Japanese passport, were destroyed in a fire at the Hotel Esmond in Portland, Oregon, in July 1918.

According to later accounts, for which Nakazawa himself was presumably the source of information, he graduated Waseda University, then attended University of Oregon as an English major. He claimed to have taught at University of Oregon, Reed College, and University of Washington.

Conversely, one newspaper story published in the 1920s related that Nakazawa’s father sent him to America to work as a common laborer in order to put a brother through studies at the Tokyo Academy of Fine Arts. A surviving World War I draft card, issued in 1918, lists Nakazawa as living in Portland, Oregon and working as a janitor.

By July 1920, Nakazawa had enrolled in a speech class at University of Oregon’s Portland campus. In February 1921, he gave a humorous speech at a department dinner on “Scientific Tickling.” During this period, he seems to have written short stories and playlets. In summer 1921, he gained his first public notice when his one-act play, The Candyman of the Temple Gate, was presented by the Portland Drama League at an all-Japanese evening in cooperation with the local Japanese consulate. Nakazawa played the eponymous candyman, Mr. Iwano. After the performance, the Morning Oregonian declared, “The Candyman of the Temple Gate was written by Ken Nakazawa, a local Japanese who is a student with Mrs. Mabel Holmes in the Portland extension classes of the University of Oregon…His style is smooth and graceful, and his little play abounds with whimsical lines and interesting situations.”

Nakazawa followed with another short play, The Fallen Blossoms. According to one story, it was first produced following the great Tokyo earthquake of 1923 at a benefit performance by the Pasadena Community Players in California, held to raise funds to rebuild Japan’s Tsuda College, heavily damaged in the earthquake. The performance proved a phenomenal success and the play was then staged in Los Angeles by the MacDowell Club and the Ebell Club. In 1928, the Hollywood Community Players put on a longer version of the play, directed by Louise Avery Hastings, with a cast that starred the well-known actors Beatrice Prentice, William Raymond and Carlo Schipa. In 1926, the play was produced in Portland with accompanying score by composer John Anderson. The Persimmon Thief, a Japanese play adapted by Nakazawa, also received amateur performances.

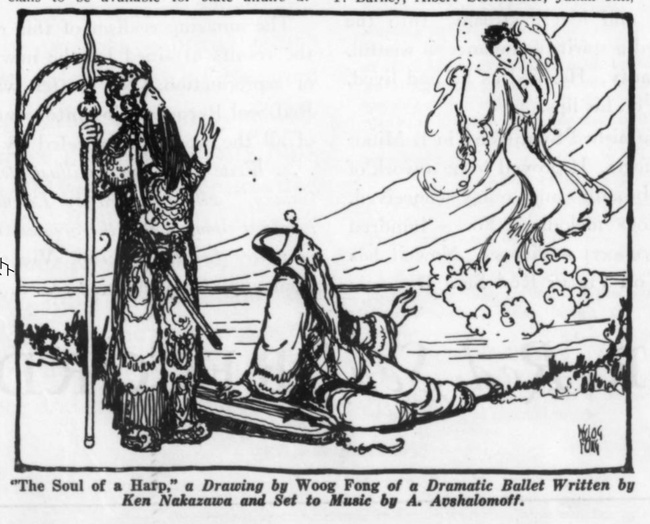

Meanwhile, Nakazawa provided the scenario for a ballet, The Soul of a Harp, featuring music by composer Aaron Avshalomoff. In 1927, the Portland Junior Symphony performed one scene, The Death of Kin-Sei. The following year, the San Francisco Symphony followed suit. The entire work was played in Tianjin, China in 1930.

With encouragement from his English instructor, Ida V. Turney, Nakazawa published pieces of short fiction, as well. In February 1924, the national magazine McCall’s published Moonbird, a Japanese folk tale told from a little girl’s viewpoint (in order to pass as the narrator, the author published under the name “Miss Ken Nakazawa”). He also published a comic article, “Treatise on Scientific Tickling Dealing With Poultry Raising.” Nakazawa’s story “The Doll Flowers,” set in contemporary Japan, was included in the 1924 book Monogatari, editor Don Seitz’s anthology volume of Japanese stories. His short story “Sting Me!” appeared in 1927 in the popular children’s magazine St. Nicholas. Nakazawa reportedly put together a collection of stories, called alternately Moon Bird or The Purple Butterfly, which he claimed was accepted by Macmillan publishers, but which never saw print.

In 1927, the distinguished publisher Harper’s put out Nakazawa’s book The Weaver of the Frost, a collection of a dozen Japanese folk tales. The Los Angeles Times referred to the book as “Full of oriental fancy that gives a peculiar flavour to legend and fairy tale,” while The Cincinnati Post praised it as “told with an oriental charm.” Carey McWilliams termed the volume “a delightful collection of Japanese fairy stories.” Witter Bynner reviewed the book favourably in The Saturday Review, but mistakenly reported that author Nakagawa was just eight years old!

Nakazawa also turned his hand to freelance journalism. During summer 1926, he wrote a series of newspaper articles for the Portland News on the Federal court case of Tokokichi Ogura, who had filed suit for damages after he was chased by a racist mob from the town of Toledo, Oregon, the previous year.

Around the same time, Nakagawa published “Horse Bandits and Opium,” an article on opium trafficking in China, in the magazine Forum. Nakazawa proclaimed that the bulk of Chinese narcotics production and sales were actually carried out by “Ma Fei,” horse bandits based in Manchuria. It is unclear where he found his information on the subject, which may have been fabricated:

Modern Ma Fei appeared about 50 years ago. It includes men of all classes and conditions. There are common robbers as well as political exiles. There are soldiers out of pay and aspirants for governmental positions. Like other bandits, Ma Fei rob, kidnap, and blackmail. But in most cases they indulge in these pursuits in order to earn the cost of opium production. That is why they are comparatively inactive-that is, inactive as robbers—during the opium season between June and August.

The article was reprinted in Reader’s Digest, adding to its nationwide circulation.

Beyond his reception as a writer and journalist, Nakazawa achieved renown as a teacher and public lecturer on diverse topics revolving around Asian culture. In fall 1921 he spoke before the Portland Flute Club about the Japanese flute, with assistance from a pair of performers. In Spring 1922, he gave a talk at Reed College on US-Japan relations. Nakazawa asserted that much hostility between the two nations could be eliminated if they would study each other’s art and literature.

In February 1926, the Crescent, the newspaper of Pacific College (today’s George Fox University) reported that Ken Nakazawa, “Japanese poet of Portland,” had come to lecture on the history of Japanese poetry in the chapel hour, briefly explaining the difference between Tonka and the Hokku (Haiku).

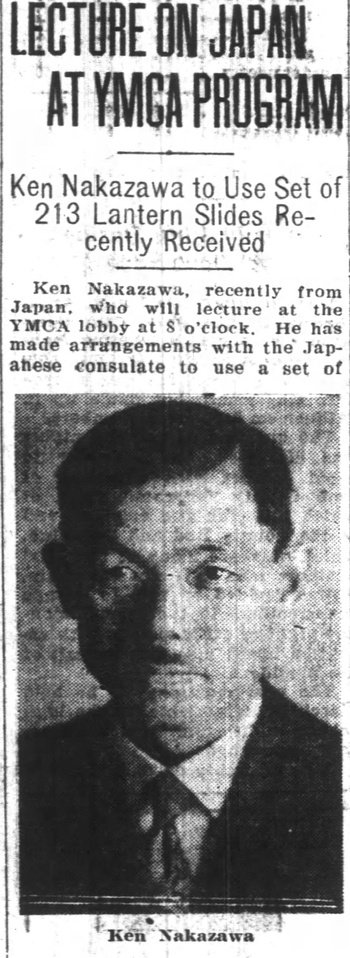

In early 1927 he spoke at the Portland YMCA, using 213 lantern slides imported from Japan. A newspaper reported that Nakazawa would give a general survey of Japanese history, art and literature, touching upon subjects such as color prints, flower art, the tea ceremony, school and home life of Japanese students, problems of modern Japanese society, poetry and drama.

In April 1927, Nakazawa travelled to the University of Oregon’s campus in Eugene, to deliver a set of illustrated lectures. A student correspondent, “L.D.,” referred to the guest as “Informally dignified, likeable and modest, with an attractive personality.”

The newspaper The Emerald noted that theme of the lectures was the history of Japanese culture and the tug-of-war between tradition and modernity in Japan. ”Mr. Nakazawa touched on the architecture of the old and the new Japan and brought out the fact that American architects have been employed in the building of the modern, earthquake-proof structures in the large cities. Japanese import a large amount of ‘American Powder’ which, reasonably enough, is not face powder, but wheat flour, he pointed out.” He concluded that the chief novelty of modern Japan was the development of a free press—there are at least 47 newspapers in Tokyo alone—in contrast to the censorship of a bygone era.

In 1926 the University of Southern California recruited Ken Nakazawa to teach Oriental art, literature and languages. He simultaneously took a salaried position in the Los Angeles Japanese consulate. He started his USC duties sometime in 1927, and in 1929 was appointed instructor of Oriental Art and Philosophy. In fall 1930, he undertook a full-year course in Japanese and Chinese literature at USC, plus a single-term course on Oriental History. It is not clear whether he ever became a regular faculty member. The 1930 census, which identified him as a lodger in a YMCA hotel on South Hope street, listed his occupation as Japanese language teacher. While he identified himself as Dr. Ken Nakazawa, and claimed a PhD from University of Oregon, it does not appear that he ever earned any degree there.

Nakazawa spent the bulk of his time preparing and delivering lectures on diverse topics. He addressed the MacDowell Club of Allied Arts on “The Background and Technique of Chinese and Japanese Drama”, spoke on Oriental art at USC School of Architecture, and in November 1927, addressed Pasadena’s 100 Percent Club on Japan’s social problems. He stated that the solution to Japan’s chief problem, overpopulation, lay not in emigration but in reorganization of Japan’s industrial system to favour production of high-quality goods. In fall 1927 he delivered a series of lectures on “The Art of the Far East” at UCLA and then at the Southwest Museum. One of these lectures, on the miniature medicine chests of Japan, was subsequently published in the Southwest Museum’s journal Masterkey: Anthropology of the Americas.

In spring 1928, Nakazawa presented at an “April in Japan” event in San Francisco; spoke on “Japanese prints” before the Los Angeles Three Arts Club; delivered a lecture on art and architecture in China and Japan, complete with lantern slides, before the Southern California Chapter of the American Institute of Architects; and lectured on Noh Drama at the Friday Morning Club.

In August 1928, in his capacity as employee of the Los Angeles Japanese Consulate, Nakazawa delivered a brief speech on Japanese art at a mammoth Japan Day celebration at the Pacific Southwest Exhibition grounds, before a crowd of 25,000 Japanese—declared to be the largest gathering of “orientals” to be assembled at one time in Southern California. Two months later, he spoke to a group of consular employees at Bridge Hall at USC, giving comments on Japanese art and literature at the end of Tokugawa period.

In November 1928, he delivered a lecture at the City Club in Los Angeles. The Los Angeles Times wryly praised the talk as an examination of Japan’s soul: “Our reverence for ancestors is based on love, not fear, and it has given Japan a sense of unity and of purity which probably no other religion or system of ethics could have inspired. Socially, Japan is much like America, only we are more clannish, our full development of the social consciousness having been delayed by the actions and ideas of the feudal war lords. Governmentally, we approach the democracy of America in reality, in spite of the fact that we are still a constitutional monarchy. Industrially, we are following in the footsteps of America. Machinery is fast taking the place of men, although, with our tremendous man-power. I could wish that my people would make a greater specialty of handwork, in which they are proficient.”

In 1933 Ken Nakazawa married Tomiko Nakazawa (née Tsukada), an educated Issei woman, and became stepfather to her three children: Karl, Albert, and Warren.

To be continued ... >>

© 2024 Greg Robinson