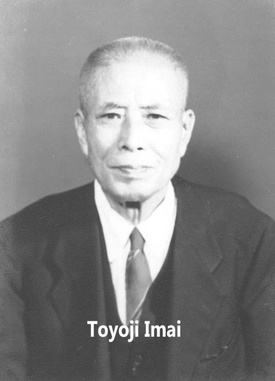

PartGrandpa Toyoji (1869-1953--from Niigata, Japan) was unquestionably a unique person, exercising complete freedom and free will. His mannerisms and actions that he displayed, his character that he portrayed, makes me think he was one that no one can ever duplicate. He would be so stern at times, and yet on the other hand he could be very compassionate and caring. Grandfather was never a physical person, in that he was never seen in the back yard garden, nor working with tools, nor involved in any food preparation – he was not a manually oriented individual.

He was indeed a scholar; he was often seen with a book in his hand (Dr. Masaharu Taniguchi’s Truth of Life books) or engrossed in writing in his waking hours. He maintained a library in his very private room that nobody could enter: it was completely off limits to everyone. He had his study desk in the very middle of the parlor with pens, a bottle of ink, pencils and sheets of writing paper, and an empty salmon can that he used for an ash tray. Grandpa was asthmatic and he suffered attacks, gasping for air. From time to time he resorted to a special “tobacco” for relief and comfort. (Uncle Richard thought that it might have been hemp or marijuana.) All was quiet whenever grandpa had one of his attacks.

Grandfather’s bedroom was also a place of privacy. Grandmother was the only person who was permitted in his bedroom, once in a while, to change his linen and to tidy the room. Mind you, this was by his invitation only. Whenever he took his daily naps, the other members of the family were not to disturb his sleep. There was to be no loud talking, nor banging of things. It was only after his awakening that the family could resume normal operations.

Everything that grandfather did was virtually a ritual and almost predictable. His going for a bath, for instance: he would emerge from his bedroom in loin cloth, like a sumo wrestler, wrapped around his waist. He would parade through the parlor, kitchen, a few steps down through the back entry, and then make his entrance into the combined laundry and – Japanese wooden bath tub - wearing his wooden clogs or geta, to immerse himself in the furo. By tradition, as head of the household, he was the first to use the furo.

Whenever he returned from funeral services or visits to the graveyard, he would not enter the home until he purified himself. He would call on grandmother to bring him a handful of salt which he would sprinkle all around the entry way before ever stepping into the home. When the whole family had to depart for any destination, he would be the last to leave the house. He would go through a ritual of repeated motions of opening and closing the door several times (perhaps five to ten times), and only then would he step out. Then Grandpa would check and recheck to see that the door was secured for certain. It was only then that he would join the rest of the family members waiting impatiently in the car. He always had a designated seat, the front rider’s seat in a Chevrolet of the 1930s.

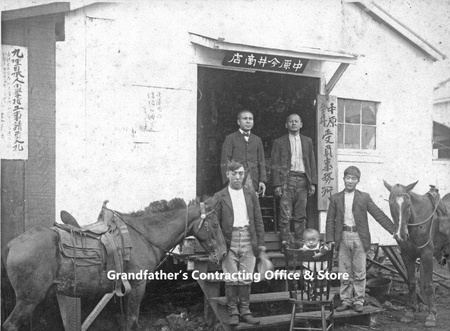

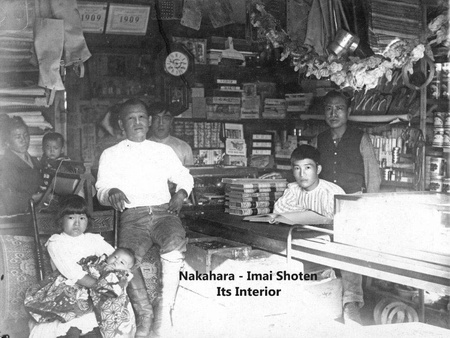

Grandfather engaged himself in a Japanese magazine distribution “business.” Perhaps this was a carry-over from his earlier enterprise as proprietor of Imai Shoten, his general merchandise store. On monthly basis, Mr. Oyama, who maintained a trucking service, made his delivery of a wooden container directly from Japan, roughly 24” x 36”X 30” in dimension, laden with magazines. As part of his service, Mr. Oyama often uncrated the box for grandfather. The shipment consisted of women’s magazine, magazines for youths, and one for the general readership. Once the container was uncrated, it was generally my chore to carry the magazines into the parlor and separate the shipment into groupings by similar titles.

Grandfather painstakingly prepared invoices for each magazine customer prior to making his delivery. Generally it took either my dad or Uncle Richard and Grandpa two to three days to complete the distribution. Grandpa had two routes – one covering Ola’a proper, Kurtistown, Mt. View, and Glenwood; the other included Pahoa and Kapoho. Being grandfather’s favorite, I went along on most of the distribution journeys sitting on his lap in the front rider’s seat. We’d leave Grandfather’s home at about four in the afternoon and didn’t get back until well into the night - eleven or twelve midnight. For grandfather these deliveries were not just business calls but were social calls on his friends as well.

Greeting New Year’s Day was so very special for all of the grandchildren. Our pockets were never ever lined with money, not at all, but this was one day that we received monetary gifts from grandpa. He would get all the grandchildren to form a line from the eldest to the very youngest and made his distribution on a descending scale. The older you were your pocket was lined with more money. He would call us by name and we presented ourselves one at a time, and received our monetary gift. Being the eldest among the grandchildren I always received the greatest amount. Even a dollar in those days was a huge amount. (One could get 20 bars of candy for a dollar.)

Grandfather, among many other things, had a favorite snack food, pan-fried sweet potatoes. He gave me instructions on the preparation of this snack and I was often asked to prepare some for him. It was rather a simple preparation: 1) wash the sweet potato, 2) Remove skin using a paring knife, 3) Slice potato into quarter inch- pieces, 4) Salt to season, 5) Heat frying pan with cooking oil, 6) Fry sliced potato until crisp.

Because of grandfather’s educational background, he was requested by community members to assist them with Japanese consulate matters. Many parents back in the ‘30s and ‘40s, for instance registered their children with the Japanese as well as the U.S. government for dual citizenship. Grandfather assisted the members of the Japanese community with some of the other consulate- related matters on voluntary bases without any compensation. On Sunday, December 7, 1941, when war was declared between Japan and the United States, grandfather Toyoji was arrested and was interned during the entire period of the war for his ties with the Japanese Consulate.

On the first night of the war, Grandpa Toyoji, Grandma, Aunty Masayo and I were at grandfather’s home in complete darkness. At about midnight, there was a loud pounding at the front door. Nobody dared to move but there was a persistent knocking at the door. Finally grandma and my aunt proceeded cautiously to the door to find a police officer and a FBI agent. I heard one of them in a sternly voice, “Is this where Toyoji Imai is living?” I heard my aunt replying in a very weak voice, “Yes.” My aunt was ordered to bring Grandpa to the door. Aunty Masayo approached Grandfather’s room and called out, “Oto-san, Oto-san”. When grandfather came to the front door, he was told by the officers to go along with them without any further word of explanation, just as he was dressed – in his kimono and slippers. It was only a day or two that we learned from Uncle Richard that grandfather was taken to Kilauea Military Camp on the night of his arrest. Uncle Richard was the sole person who was permitted to visit grandpa and also to deliver his personal belongings.

We learned later that Grandfather was initially taken to KMC in Volcano, later to Sand Island on Oahu for a brief duration,(then to Camp Livingston, Louisiana) and on to (the Justice Department detention) camp &mash; in Santa Fe, New Mexico for the duration of the war. As with the other internees, Grandfather returned home to Hawaii at the termination of the war. I was so impressed with his expression of love and humbleness for his adopted country because even after his four long years of internment and separation from his family, he showed no form of remorsefulness, animosity, or resentfulness toward the United States Government or the system.

*This article is an excerpt from Our Nostalgic Heritage: Growing up in a Place Once Called Ola'a (2014) from pages 33 - 36.

© 2014 Akinori Imai