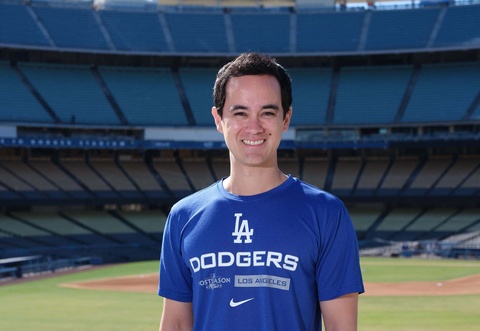

What becomes clear after meeting Will Ireton is that there is more to him than meets the eye. Much more.

In his eighth year as part of the Los Angeles Dodgers organization and in his second as the Performance Operations Manager, Will’s career path included playing minor league baseball for the Texas Rangers, helping to organize the Philippines’ national team for the World Baseball Classic (WBC) in 2015 and acting as the translator for one-time Dodger starting pitcher Kenta Maeda from 2016-2018. It was during that stint that Dodger President of Baseball Operations Andrew Friedman dubbed him, “Will the Thrill.” Other diverse bits of information include the fact Will grew up in Tokyo and that he once deadlifted over 400 pounds on a dare from a Dodger player.

First, most Dodger fans are probably wondering, “What does the baseball Performance Operations Manager do?” If you have never heard of this position with the Dodgers, it is because it never officially existed before Ireton transitioned into the job as Performance Operations Coordinator in 2020. To understand the focus of his work, Ireton points to the key word in his title: “I think when we say performance, that is the buzzword. What matters the most is the players performing on the field. Anything that touches their performance is what I do.”

Will then referenced Michael Lewis’ book, “Moneyball: The Art of Winning An Unfair Game” which was also made into a movie. In the book, Oakland Athletics’ general manager Billy Beane, who is cash-strapped, finds an advantage by tapping into game statistics that traditional baseball front offices used to ignore. The one-time novel approach, known as sabermetrics, emphasizes on-base and slugging percentages over traditional statistics such batting averages and runs batted in.

Ireton’s job is to help the players and coaches use the sabermetric data along with other newer technologies to enhance their performances on the field. “I’m on the ground with the players,” Will explained. “I don’t have a lot of peers working side by side. We use Trackman (a technology made famous by professional golfers) and motion capture technology before the game to aid the pitchers. We look at hitters’ mechanics by letting them see how their bodies move in relation to a pitch. It’s hands-on working with the players.”

One of the factors that helps Ireton in his job is that he once aspired to be a major league baseball player. He was born and raised in Tokyo, Japan, to a Nisei father (his father’s mother is Japanese from Nagoya and his paternal grandfather is Irish Catholic from New York). Will’s dad William met his mother Rosario Trinidad, who is Spanish-Filipina and Catholic, while visiting the Philippines. Will attended public schools growing up because his mother wanted him to learn the Japanese language.

Eventually, he enrolled in an international school and baseball was his obsession. At age 15, Ireton left Japan for Honolulu, Hawaii, with the objective of furthering his baseball career. But to be clear, Will was looking for balance in his life. “I had a choice of attending a local school (in Japan), but it would have been baseball dominant,” Ireton recalled. “I wasn’t comfortable with that.”

Instead, he enrolled in the Mid-Pacific Institute in Hawaii because “it balanced scholastics and sports. I home stayed at my family’s friend’s house. I was a home body by nature, but I didn’t know that until I moved. I wanted to pursue my goal (of playing baseball).”

Upon graduating from Mid-Pacific, Ireton moved to the mainland and attended both Occidental College and Menlo College. Because of his mother’s nationality, Will was eligible to join the Philippines’ national baseball team in 2012 and took part in the World Baseball Classic (WBC) qualifying tournament.

The team failed to qualify, but the experience got Ireton a tryout with the Texas Rangers and he played at the A level at second and third base.

It was at this point that the reality hit Will that he was not a major league player. “I had to be at my 100 percent best to compete (at the A level),” he explained. Given that, he needed to sort out his other options. “I didn’t consciously have a Plan B,” Ireton noted. “But I really loved baseball.”

With an adjusted career path, Will did internships with the Rangers and the New York Yankees where he learned more about how baseball organizations worked. He gained even more experience when in 2015, he served in a general manager capacity for the WBC Team Philippines.

Having played for the Philippines in 2012, he knew the job was challenging. The two biggest sports in his mother’s home country are basketball and soccer. Baseball is pretty far down the list.

“It was like being a general manager for a professional baseball team,” Will revealed. “We had an acting owner. I had to go scout players. I had to find coaches. I had to find practice fields and make travel arrangements.”

Essentially, Will had to find players like himself who were connected to the Philippines, but had played baseball at a professional level. “The most talented players were some who played in the Little League World Series (years ago),” Ireton said. “Most of them were in their 30s. Maybe one player was physically gifted. Most were Division II (collegiate) players.”

Team Philippines competed in the WBC qualifying tournament in Australia, but it did not advance. But the experience helped provide Ireton with a boost to his career goal of working for a Major League Baseball (MLB) team.

His other advantage was growing up in Japan and learning to speak fluent Japanese. Since Hideo Nomo left Japan to play with the Dodgers in 1995, some of the best Japanese players began coming to America. In 2016, the Dodgers signed Kenta Maeda as a starting pitcher and Maeda needed a translator to help work with the coaches and the media.

Opportunity, meet Will Ireton.

Because of Will’s baseball background and his Japanese language fluency, he was hired to work with Maeda. Ireton found the Dodger work culture much to his liking. “It’s collaborative,” Will explained. “The players, coaches and the front office all value a hard work ethic. That part hit home with me. I was familiar with baseball culture. As a first-year employee, I wanted to do anything to help. Picking up baseballs or helping out in the weight room. Once everyone saw that, they were welcoming.”

Ireton participated in all of Maeda’s meetings with then pitching coach Rick Honeycutt and with the Dodger catchers. He helped with the details including counting the number of pitches Maeda would throw in the bullpen and letting Kenta know when to expect the National Anthem to be sung at games he was starting.

Asked if he could see the similarities between the Dodger work culture and Japan’s work culture, Ireton said, “I do. It helps that the old school values—working hard, humility, blue collar—fit in with the Dodgers. I played on local baseball teams in Japan. It built my work ethic. My tolerance to work hard was built in Japan. The values translated from Japan to here.”

It was also during this stint with the Dodgers that Friedman dubbed Ireton “Will the Thrill.”

During batting practices, Will would help to shag balls in the outfield. But he impressed the Dodger president and the team by going all out to catch fly balls, diving and straining as hard as he could. In a story on SportsNet L.A., former Dodger Justin Turner observed of Will, “Everything he does is to the max. He’s out there power shagging (baseballs), trying to make diving plays and sliding catches. It’s been fun to have him on the team.” To make his nickname official, the team gave Ireton a uniform with the name “Will the Thrill” on the back and the number 1.8 (Maeda’s number was 18).

It was also in this period that Ireton amazed the entire team when he agreed to dead lift 405 pounds. “I am definitely not a weightlifter,” Will said. “I was challenged to lift 405 pounds by a player and I ended up having to lift it in front of the entire team in Spring Training. I am 5-10, 160 pounds. I did train with a Dodgers' strength coach.”

After the 2018 season, Ireton became a development coach for the Dodgers’ AAA affiliate in Oklahoma City. It was here that he learned how to apply technology and data to the day-to-day operations and also got some experience coaching first base.

“I scouted all the opponents and wrote scouting reports based on the data,” Will summarized. “It was so the pitchers and the hitters had generic plans to attack their opponents. I did a lot of game planning. Also, when the pitching coach would request technical help with the motion capture and ball tracking technology to look at a player’s different pitches, I was there to assist.”

In 2020, Ireton was promoted to the newly created position of Performance Operations Coordinator, working in a similar fashion as he had in Oklahoma City. Will explained that in doing his work that it was important to recognize that each player is an individual and support must be tailored to suit them.

Asked if all the players were open to getting the extensive data now available, Ireton noted, “We respect the individual players and their comfort level. When players are playing well, it’s no problem. But when a player is slumping, we let them know resources are available. The most important voices are the coaches and the players. The coaches are driving the process.”

As a Nikkei, it is not lost on Ireton that he belongs to a growing group of Dodger players and front office employees who are of Japanese and Asian ancestry. As mentioned above, Nomo opened the doors for other Japanese players to come to America and the Dodgers recruited pitchers Takashi Saito, Kazuhisa Ishii, Hiroki Kuroda and Maeda from Japan. But the team also signed other players from Asia, including Chan Ho Park, Hyun-Jin Ryu and Hee-seop Choi (South Korea) and Hong Chih-Kuo (Taiwan).

People of Japanese ancestry have been working for the Dodgers almost since their arrival in Los Angeles back in 1958, including clubhouse manager Nobe Kawano and front office workers Irene Tanji and Ike Ikuhara. Recently, in a public program organized by the Japanese American National Museum and the Dodgers entitled, “Beyond the Dugout: A Discussion with the Japanese American Staff at the Los Angeles Dodgers,” Ireton was part of a panel that included Dodger manager Dave Roberts, Senior Director of Team Travel Scott Akasaki (who was key to the creation of the program), Stephen Nelson, in his first year as a Dodger broadcaster, and Emilie Fragapane, an analytics and biomechanics specialist.

At the panel, it was revealed that Ireton maintains a regular ritual with Roberts before each game. According to Nelson, 30 minutes before the game is scheduled to start, Will delivers a cup of green tea for the Dodger manager. There’s something extremely appropriate about this custom between two individuals, one whose mother and the other whose grandmother were born and raised in Japan.

The Dodgers since the days of Jackie Robinson have been a leader in inclusion for its staff and players and Ireton recognized that it was a privilege to work for such a team. “It’s an extreme honor to be part of an organization that’s known for forward-thinking, accepting diversity and just being part of the community,” Will stated. “That’s the brand that the Dodgers are known for, and now that I’m working here, I do believe that we follow the philosophy from the inside out.”

Of his current situation, Will said, “The best part in general is that I really like baseball and to be part of a major league organization at a major league level is an honor. I am very excited that I am here.”

One would expect no less from someone dubbed “Will the Thrill.”

© 2023 Chris Komai