Arthur Hansen has spent the past 50 years researching and writing about the World War II Japanese American incarceration, one of the ugliest chapters in American history, in which 120,000 people of Japanese descent were summarily exiled to remote, desolate prison camps, their civil rights having gone up in smoke along with the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

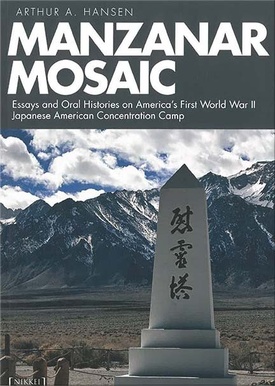

His latest book is Manzanar Mosaic: Essays and Oral Histories on America’s First World War II Japanese American Concentration Camp. Recently Discover Nikkei spoke to Hansen, an emeritus professor of history at California State University, Fullerton, and founding director of the Japanese American Project of the Oral History Program and the Center for Oral and Public History, about his latest work.

The first part of the book is made up of two scholarly essays that Hansen co-wrote, one with David Hacker on the Manzanar “riot” of December 6, 1942 (published in Amerasian Journal 2 in fall of 1974) and another, unpublished essay co-written in 1975 with Ronald C. Larsen about the history of the Los Angeles-based left-wing Doho newspaper.

The latter part of Manzanar Mosaic is made up of five oral histories that Hansen and others recorded between 1973 and 1976. We hear the voices of Sue Kunitomi Embrey, Togo W. Tanaka, Karl G. Yoneda, Elaine Black Yoneda, and Harry Y. Ueno. Hansen suggests that reading the oral histories first and then returning to the scholarly essays will make it easier to follow the various characters, political factions, and interpretive arguments contained in the essays.

Sue Kunitomi Embrey and the Oral Histories

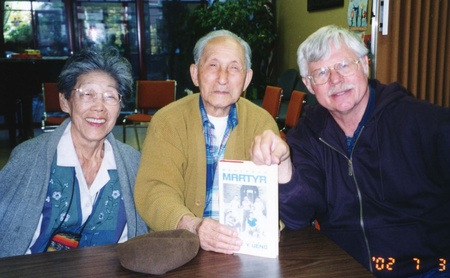

Hansen’s first interview, carried out with David Hacker in 1973, was with Sue Kunitomi Embrey, a Nisei activist from Los Angeles. Even though many had warned him that the Japanese Americans would not speak to him, the interview was a success, which gave him the confidence to do more. Hansen and Kunitomi Embrey became fast friends, too, and went on to conduct many oral history interviews together.

“I valued her knowledge, her friendship, and her forthrightness,” says Hansen. “She was a very skilled person, she was fun and gentle and she didn’t turn people off. She worked well with people across community and class lines. She was a rare person with rare talents.” Yet her biggest contribution, he believes, “was to get Manzanar recognized as a National Park site. I’m not sure that it would have happened without Sue.”

In her oral history Kunitomi Embrey remembers what it was like in Little Tokyo after the issuance of Executive Order 9066, and describes influential members of the pre-war Japanese community and within Manzanar. Many times they were the same people. Togo Tanaka, for example, a UCLA graduate and co-editor of the Little Tokyo-based Rafu Shimpo, was intensely pro-U.S. government despite being arrested among the first wave of suspected “enemy aliens.”

Another of Hansen’s interviewees, Tanaka went on to write a history of the Manzanar riot, in which he identified three different inmate factions: the Japanese American Citizenship League (JACL) group, which supported the American government’s war effort and later encouraged Nisei to enlist in the U.S. military; the anti-JACL group, largely Issei and Kibei (born in America but raised in Japan) inmates; and the anti-administration, anti-JACL group.

A fascinating oral history of Kibei Karl Yoneda illustrates how at times inmates could be members of two seemingly opposing groups. Yoneda was a passionately committed member of the Communist Party, a union activist, and in Manzanar, a staunch opponent of fascism. His unwavering support of America’s opposition to Nazi Germany put him in league with the pro-American JACL. “They were in opposition before the war, but it was a marriage of convenience during the war,” says Hansen.

Leftists like Yoneda not only wanted to fight Nazis, they also fervently wanted to see American open a second front to help out then-ally Russia. Yoneda, Hansen points out, did not just proselytize, he acted on his beliefs. From Manzanar, he volunteered to attend the Military Intelligence Service language school, then served in the Chinese-Burma-India theater in the Office of War Information.

Also included in the oral history section is an interview with Elaine Black Yoneda, Karl Yoneda’s Caucasian wife and mother of their son Tommy. The daughter of New York Russian Jewish parents, she and her future husband met in 1931 when, as an employee of the International Labor Defense organization, she bailed him out of jail after he had been beaten and arrested by the Los Angeles Police Department for participating in a labor demonstration.

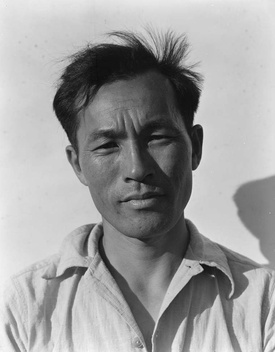

The final oral history interview is with Harry Ueno, the dissident cook at Manzanar whose arrest touched off the incendiary riot on December 6, 1942. The evening before, masked inmates assaulted Fred Tayama, a prominent Nisei business leader in Los Angeles before the war, but an unpopular figure due to his exploitative labor practices, his alleged role as a government informant, and his championing of accommodationist JACL policies. Ueno, as the leader of the 1,500-member, Kibei-dominated mess hall workers, was arrested for the crime, but many believed he was framed.

The Making of a WWII JA Incarceration Historian

Hansen’s own first encounter with Manzanar came in 1960 when he was a senior at U.C. Santa Barbara and wrote a term paper for a sociology class on what was then called “the Japanese American Evacuation,” a euphemistic label that reflects the still-unprocessed nature of the traumatic experience.

It had only been fifteen years since the closure of the concentration camps, and was a time when those who had been imprisoned were doing their best to move on. The topic interested Hansen because he had grown up with Japanese American friends in nearby Goleta before the war. While doing research for his paper, he interviewed the parents of his Sansei friend Norm Nakaji.

“I did a lousy job, explains Hansen, because I didn’t do primary research into the archives, and just relied on accounts in popular magazines like Time and Newsweek for information. They were caught up in the fable that the incarceration was good for Japanese Americans because it broke up their Japantowns, that it was a blessing in disguise.”

It wasn’t until 1972, when he switched his focus from Anglo-American intellectual history to the World War II Japanese American experience that he found his life’s calling. His best friend and history department colleague, Dr. Kinji Yada, had been an adolescent inmate at Manzanar. That same year, Hansen went on his first Manzanar Pilgrimage with Yada, launching a nearly yearly practice of taking students there. It was not just groups like the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee, or principled resisters like Gordon Hirabayashi and Fred Korematsu that captured his imagination.

In graduate school, he had been drawn to the topic of radical movements and their origin. In the Manzanar Riot, which grew out of the protests of a marginalized group within the prison camp, and the story of the communist newspaper Doho, he recognized the threads of alternative, dissident thought within the Japanese American community.

Most scholarship up until that time had focused on general studies of the incarceration, or the heroic actions of the 442nd Regiment, and less so on resistance. Hansen focused on the Japan-educated Kibei-Nisei prisoners, who were marginalized and scorned by Nisei raised solely in America; the small cadre of Communists in the Japanese community before World War II and in the concentration camps; and the labor unionists who agitated for better pay and treatment within camp and butted heads with more assimilationist groups like the JACL.

In the first of two essays Hansen includes in Manzanar Mosaic, “Doho: The Japanese American ‘Communist,’ Press, 1937-42,” he and co-author Larson describe how the newspaper and its staff were “heirs to an impressive heritage of Japanese American socialists,” like the Christian leader Katayama Sen, explaining how the newspaper belonged to a long line of leftist Japanese publications. It was the voice for working class Japanese unions organized by gardeners, farmers, and other laborers. Yet at the same time Doho played an important role as a community newspaper, offering readers practical support and guidance in navigating life in America.

In the second, 1974 essay on the Manzanar uprising, Hansen and Hacker explain and refute the prevailing War Relocation Authority (WRA)-JACL framing of the event, which reduces it to a simple pro-American versus pro-Japanese dispute. They also disagree with its interpretation as either an “incident” or a “riot,” both of which, they say trivializes its cultural significance without examining the causes that led up to the event, or how it fit into a larger pattern of resistance throughout the camps.

Proposing what they call “an ethnic perspective” on the matter, they pointedly call the incident a “revolt” rather than a riot. Hansen explains how the idea evolved over the summer of 1973, when he and David Hacker were driving from Fullerton to the UCLA Japanese American Research Project archives three or four times a week, discussing the issues intensely and beginning to see patterns.

They realized that what happened on December 6, 1942 was not a spontaneous eruption of anger, but the breaking through of a growing discontent on the part of the mostly non-assimilationist Kibei that had been building for years before camp and continued inside the prison, where, he notes, “they had been demonized by camp leaders.” Many happened to be mess hall workers, and they coalesced under the leadership of Ueno. He became a rallying point around what they perceived as threats to their cultural heritage and identity, which was much more aligned, like the Issei generation, with Japan than with the U.S.

What is interesting to future scholars in these areas is Hansen’s acknowledgment of more recent analyses of the Manzanar riot, one re-casting it as a class conflict between educated, cosmopolitan Nisei and their rural, less educated counterparts. Another scholar criticized Hansen and Hacker for not considering the revolt’s wider, global context. In response to all of them, Hansen says, “people now have access to so many different data bases, new knowledge and new sources.”

When he co-wrote these essays and conducted the oral histories, he acknowledges, “there were still plenty of Issei alive, and the Nisei were still quite young.” As those generations passed, he wondered if interest in the history of the World War II incarceration would die out. But he notes that not only has interest persisted, but the Yonsei and Gosei generation “are starting to do some really good work.” He adds, “It’s nice to see this.”

Hansen has no doubt that history could repeat itself in this time of political polarization and vast income inequity. Just as they did during the fight for redress, he adds, “More Japanese Americans need to step away from safe harbors and take up positions they stood up for at the time of the redress movement.” He points to the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations, and how they have continued their work as Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress. “They’re still fighting for progressive causes for all people.”

Hansen himself has no plans to stop his life’s pursuit. He is currently working on three manuscripts that he hopes will become published books. One of them deals with the 1942 diary of a Manzanar camp administrator; a second examines the World War II incarceration experience of Japanese Americans in Arizona; and a third study spotlights iconic figures associated with the “social disaster” of Americans of Japanese ancestry during World War II.

“I feel fortunate, even honored,” he says, “to have had the chance over the past half-century to contribute, along with many other researchers, to the illumination of a previously neglected topic of the Japanese American Incarceration: how individuals and groups within the Nikkei community resisted their unjust oppression by the U.S. government as well as by the leadership of the Japanese American Citizens League.”

* * * * *

SPECIAL FREE EVENTS

The Enduring Power of Oral History: An Afternoon with Art Hansen & Friends

At Tateuchi Democracy Forum. Japanese American National Museum

Saturday, Nov 04, 2023 from 2:00 p.m. to 3:30 p.m. (PDT)

Noted Japanese American scholar and oral historian Arthur A. Hansen is guest of honor for an afternoon of reminiscences and oral histories from fellow scholars and friends. Bruce Embrey, executive director of the Manzanar Committee, will serve as moderator.

*Tickets to this program do not include admission to JANM. Admission to the museum may be purchased separately.

© 2023 Nancy Matsumoto