Hiro-chan, asagohan yo! – that’s how my mother would call me for breakfast, as I promptly got up with joy and an eagerness to savor a plate of rice alongside the nutritious misoshiru!

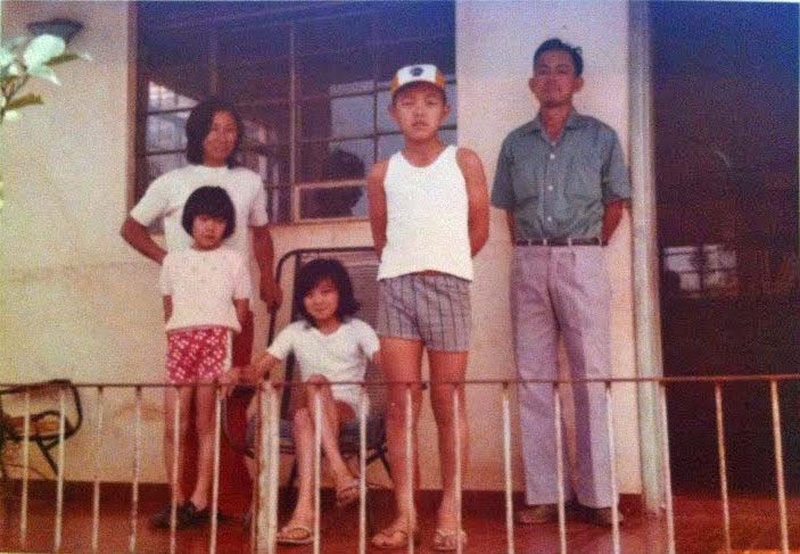

At that time (from the late 1960s to the late 1970s) we lived in the interior [of São Paulo state] – in the small town of Osvaldo Cruz, in the Alta Paulista region – so it wasn’t easy to get the necessary ingredients to prepare Japanese dishes. Immigrants and their descendants improvised with whatever was available in Brazil, and my mother was no exception: Dona Takeko, better known as Dona Carmen, fully aware that her youngest daughter loved sashimi, had to make do with sardines – and I savored them with delight! There was a hibiscus garden at home that allowed the making of ume preserves, which had a tart flavor similar to that of umeboshi, which are made with Japanese peaches.

Shiro gohan (unseasoned rice) was a must-have staple, whether it was made with Brazilian rice or mixed with mochigome (very sticky Japanese rice). Unmixed mochigome was a luxury item used only on special occasions. Shiro gohan was also used to make onigiri (rice dumplings). Which child wouldn’t have been delighted with something like that?

When it comes to stories about food, my father also has a strong presence in my recollections.

Hiro-chan, Tupã ni yoji ga arunode, issho ni ikoka? “I need to take care of something in [the municipality of] Tupã. Do you want to come along?” – that’s how my father would ask me to keep him company. We would travel to the neighboring town either in our little VW Beetle or in the VW Brasília.

I went along happily, knowing that I would get the chance to eat some nabeyaki at the bus station’s restaurant, which had a Nikkei owner. There weren't any fancy imported ingredients like those we have now, but the nabeyaki toppings were great – it even had kamaboko (fish cake)! And on top of it, there was a fried egg with a soft core that I found intriguing. It had a truly unique flavor; even after all these years, I haven't been able to find it anywhere else, nor have I been able to recreate the broth’s flavor at home.

My father didn’t even have to say, “Mottainai! Zembu tabenasai!” (“What a waste! Eat the whole thing!”), as the nabeyaki had already met its noble end!

Obento was a mandatory item whenever we went traveling. Onigiri went well with steak, omelet, ume, and even sausage, in what was a “multilingual” mix. We had to be careful not to include – the very smelly – tsukemono (pickles) whenever we traveled by bus. That was a spectacle in itself. Another culinary item, the mochi (dumpling made with pounded mochigome) wasn’t just for New Year’s; I wanted ozoni all the time. Hot mochi in shoyu broth is so delicious! Many things have a wonderful taste when they’re topped with chopped chives!

Food is what first comes to mind in our emotional memory, but my parents also greatly valued education, reading, and knowledge, so that our house, though small, had two bookshelves. That’s where you’d find my mother's women's magazines from Japan, my father's boy-oriented manga, along with the Barsa encyclopedia, and the great classics of Brazilian literature (Guimarães Rosa, Érico Veríssimo, etc.) that my mother used to read.

I found the magazines fascinating, what with their colors and variety of subjects. Also, the art of handicraft awakened something in me; so much so, that I still practice it today. My mother taught me crochet by reading visual guides.

I was a manga fanatic. My father used to read them to me, and these were great moments of companionship, as he spoke the lines and onomatopoeic words with feeling, making the stories even more fun. Manga made me want to become a graphic artist and helped me a lot in the learning of Japanese. I eagerly awaited each new issue to find out how the stories unfolded. These were children's books with very thick pages – the quality of their printing unavailable over here. They left me in awe.

The colors, the shapes, the delicacy, and the subtlety of Japanese artworks found a place in my heart and I have kept them there to this day.

Whenever my father traveled to São Paulo [the state capital], he would bring back with him gifts for his children. The crayon pencils in the little box was something magical! Tanoshimi!

It was my dream to attend nihon gakko (Japanese language school), as I wanted to decipher the many books that surrounded me, but that turned out to be impossible at the time. Even so, I was not denied access to book #1 in the series of books printed in Japan for Brazilian Nikkei readers. Nippongo no. 1 ... Sora aoi Sora... Everyone from that time surely recalls this series of textbooks.

The undokai (multi-sport event), which was held at the start of every New Year at the ADOC [Portuguese-language acronym for the Sports Association of Osvaldo Cruz], was unforgettable. Everyone in my family took part in it. I confess that I ran like a mad person on the rough terrain and oftentimes came in at least in third place, except when I was still too young and my little legs couldn't handle the effort. The prizes were a spiral notebook, notebook cover, pen, and pencil, as incentives to study. The children who were given the notebooks felt very proud... With her fast feet, my mother was unbeatable; dropping the baton in a relay race was unthinkable!

At that same ADOC, the baseball championship was a must. Nikkei families brought along obento and filled the stands. It was a good time for teenage girls to check out the young Nikkei heartthrobs. My hometown team went on to win several championships. That’s also where the Mardi Gras festivities were held, but my mother allowed us to go only to the daytime parties, which were quite discreet as Japanese cultural mores demanded.

Another New Year’s memory was the custom of kids going to the homes of Nikkei families to wish them a Happy New Year in the hope of earning a few bucks. It was a deeply rooted tradition. Tanoshimi was the word that best defined the children’s feelings on this occasion. Since we lived in a rural area, we used to go only to my aunt's house, which was very close to ours; even so, my sister and I, our hearts pounding with anticipation, would run out there after receiving my mother’s go-ahead. I can’t recall what I did with the coins I received; I remember only the joy of receiving them.

I can’t help but mention the event that did away with the monotony of the July school holidays: the Egg Festival in Bastos, “the egg capital” and the town with the highest concentration of Nikkei residents in the region. Egg farms require daily and intensive labor, and the Nikkei, who are used to that kind of work, fared well.

This event also helped me to become aware of our big world. I marveled at the colors and all the novelties. Such a diversity of Brazilian and imported products. Agricultural machinery, aviaries. Foodstuffs from Japan and other countries. That’s where I became acquainted with the delicious Milkis, a milky and sweet drink. There were stalls selling the ultra-Brazilian pastel, along with udon and ramen; there were regional associations performing the traditional odori (typical Japanese dance); and there was the perfection of the various crafts, especially the kimono-clad dolls.

At the Bon Odori Festival it was fun to get together with my cousins in front of the kaikan (the association’s headquarters) to watch the women dance in traditional costumes. We used to join at the end of the line as we tried to imitate their movements. My cousin, who was two years older than me, did a good job of replicating their body movements; I was the littlest one in the group, so I had to make a real effort.

The kaikan was a simple assembly hall, nearly attached to a Buddhist temple that held prayer services for the dead. Wedding parties, birthday parties, and other events were all held at the kaikan. The speeches were long and in Japanese, so the starving children were forced to endure that torture. At weddings, the Banzai (“Viva!”) cry was heard, mingled with Bibaaa! – with a Japanese accent.

An uncle of mine celebrated his 60th birthday there and even staged a play honoring the anniversary of immigration. He, who had arrived at age 16 in Brazil, recreated the role of a newly arrived immigrant and the difficulties of finding himself in a faraway land that was radically different from his native country.

Today, after so many years have passed and as I currently live in the largest city in Latin America, the simple days of the past will never return. Yet three words from that time define my way of life: Tanoshimi, the joys of good expectations that bring to mind many dreams and possibilities; Mottainai, the avoidance of wastefulness, which taught me to live my life without ostentation, with discretion; and the word that my mother frequently used, Arigatai, gratitude, as she counseled us to be grateful for what we had, especially for our health.

I still have many dreams and, if in the past I wasn’t given many opportunities, today I can rely on the Internet. This tool has enabled me to make my dreams come true.

About 4 years ago I started watercolor painting; about 3 years ago I bought an online course to improve my Japanese; and I’m planning on following several manga drawing tutorials on YouTube.

I am very grateful to my parents for the childhood they provided me. They were simple, intelligent, and wise people who knew how to show their children the vastness of the world, while encouraging their gifts and talents, and nurturing their dreams.

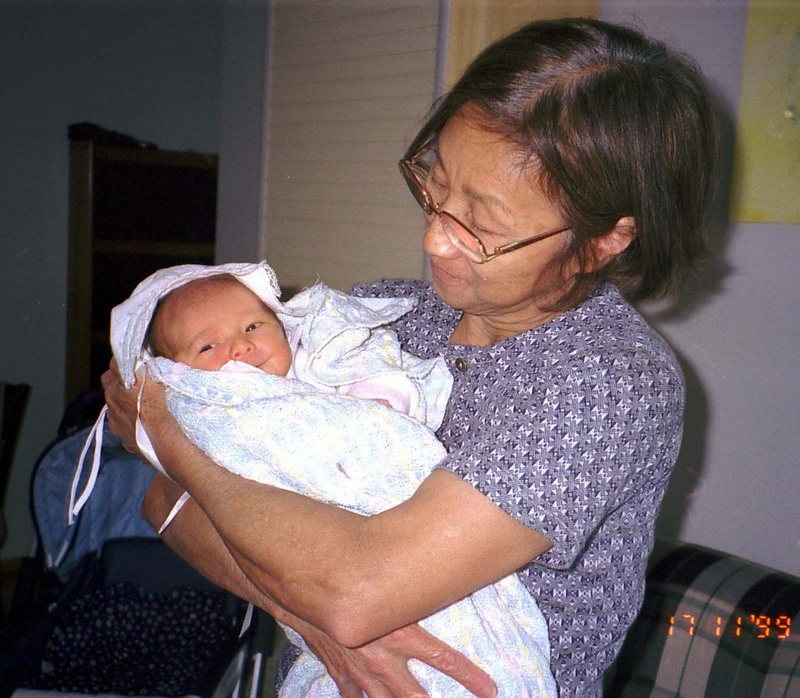

They are no longer with us, but I’m aware of their legacy when I see my daughter, now an adult, being an ethical person. (My non-Nikkei husband also deserves credit for that.)

I’m also aware of it when I see her fondness for manga and the illustrations she creates. When I see her handicraft skills while making costume jewelry with wires and stones, as well as her taste for Japanese cuisine. And I'm happy that she realizes that there are thousands of possibilities in this vast world of ours and understands the importance of believing in her own potential.

Arigatai! Arigatai!

* * * * *

Our Editorial Committee selected this article as one of his favorite Growing Up Nikkei stories in Portuguese. Here is his comment.

Comment from Laura Honda-Hasegawa

Growing Up Nikkei had the participation of five Brazilian Nikkei women who explained how Japanese culture influenced their lives, while also opening their hearts so as to lay bare their feelings, perceptions, and doubts about their Nikkei identity. Since we received several amazing stories, our attention was gripped by those filled with the most interesting situations, which in turn made our task of selecting just one incredibly difficult. Ultimately, we chose the story that fully addresses the proposed theme: “Arigatai!!!”

Its author, Edna Hiromi Ogihara Cardoso, duly shows how her life has been connected to Japan since childhood: the arts, cuisine, language, manga, imported magazines, Nikkei community events. Today, Edna shares with her young daughter the rich heritage that has been passed on to them and, along with their family, they all give thanks for everything! Arigatai!!!

© 2023