Waimea Valley IV

We enter the valley silently, without shaking the branches.

We enter without startling. Alae ‘ula watches us

from the estuary remembering the pitch nights

when the fire lived only in her. We followed

the pig trails listening for the rustle grunt

of Kamapua‘a. In the quiet, our thoughts

are small gods. They fly above the earth.

—Poem from Laurel Nakanishi's collection Ashore

As I stay da outgoing Tony Quagliano poetry award champion, da Hawai‘i Council for the Humanities wen go ask me for judge da contest for crown da next winner. Dey gave me all da blind submissions wea I nevah know any of da names of da poets. Aftah I made my selection, it wuz revealed da winner I chose turned out for be Laurel Nakanishi, one 40-year young poet from Kapālama, Hawai‘i. Congra-choo-ma-lations to Laurel!

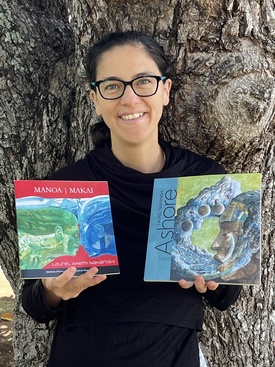

Besides being da reigning Tony Quagliano Poetry Award champion of da world, Laurel get even more poetry accolades, brah. In 2013, her poetry collection, Mānoa/Makai wuz Epiphany Edition's prize winning chapbook. An'den in 2018 her second book, Ashore won da Berkshire prize from Tupelo Press.

I only knew Laurel through reading her beautiful work so I thought for dis installment of my Much Mahalos series it might be kinda good fun if I got for talk story with her for learn more about da poet behind da poetry.

* * * * *

What school you went? What year you grad?

Growing up I did a tour of all the small private schools. So I went to Montessori Community School and then Assets and then Montessori again and then La Pietra and then I graduated from Mid-Pac [Mid-Pacific Institute] in 2002.

What area you grew up and what your fondest memories of that area?

I grew up in Kapālama, which is where I live now. Because I was living on the U.S. continent and Nicaragua and Japan and then I came back home again after plenty years of living in other places, I'm so grateful to get to know this place, Kapālama, again, as an adult.

I have so many memories of Kapālama as a child, like walking over to Kamehameha Shopping Center, or going to play in Kunawai Springs, which is actually in the Nuʻuanu ahupuaʻa [land division]. Now coming back as an adult, I'm trying to get to know more other levels of the story of this place. Like, how come the cemetery at the end of my street is named Puʻukamaliʻi? Where did it get that name? Who's buried there? Like those sorts of questions.

What your ethnic backgrounds?

My dad Blake Nakanishi, on his side, I'm fourth generation Japanese American. So yeah, Yonsei. And then my mom Jenny, on her side, her family's from Scotland, Sweden, Ireland, and England. But she and her family were from Montana on the U.S. continent.

You identify as Local? Local Japanese? Hapa? Japanese American? Nikkei? Any of these labels?

Yeah, any of those ones. Kind of depends on the social situation too, right? When I went to school on the U.S. continent, I would probably not say Nikkei or Hapa. I would probably just say white and Japanese American.

Who you most grateful to in supporting your journey in becoming one poet?

I know you had said you wanted me to limit it and not thank the whole world. So I just got two.

Two people is okay.

Well, two groups of people.

(Talking real fast before Lee can object) Okay, so I'm dyslexic. and I had a really hard time learning how to read and write. And so I was thinking back and I was like, well, it took my parents, to notice something was happening with me in school. It took my teachers to notice and care. It took our generational wealth and stability that my parents could afford to send me to a private school like Assets, which is where I learned how to read and write. So it took my grandparents, my great grandparents, you know, all of them working hard, to make it so that our family had a foundation where I was able to have that access.

And then, it took all of my teachers working really hard throughout the years. This is a lot of people I know, but they're all really important. It took all those people, all of those generations, just so that I can read and write. And that's the first step, right, if you want to be a poet. Okay, so that's ONE GROUP of people.

Wait. Family and teachers. Das two!

(Laughing) No, that's only ONE because in my mind they're part of my same educational community. And so the other group is actually a place.

I am grateful to Hawai‘i, O‘ahu, Kapālama, which is the place that has formed who I am as a person, right? So as a poet, you need to know language. You got to be able to read and write, but you also have to have something to write about and that comes from connection. It comes from curiosity of where I was born and raised and all of the layers of history that has gone into that place.

So when you wen decide that you wanted for pursue this poetry thing?

When I was young I hated reading and writing. I didn't want anything to do with that. But that changed probably when I got to high school. I started to write poetry at Mid-Pac. My teachers Yukie Shiroma and John Wat, those two were my mentors there. Even though they weren't poets, they were professional artists. And it got me thinking, "Wow, these people are teaching in the day and they're doing these amazing projects at night or on the weekends" and I just wanted to be a part of that arts community and write. And that's when I really started to be excited about writing.

You wen get one grant from the Japan-US Friendship Commission / National Endowment for the Arts. What you did for that project?

So that's a project where I was doing research for a book of lyric essays I'm writing on the Shikoku Henro or the 88 Temple Pilgrimage. This is a pilgrimage that my Grandma, Yoshiko Nakanishi did three times when she was still alive.

I remember her going on these pilgrimages and I always asked her, "Grandma, can I go? Can I go?" But she'd say, "Oh, you're too little yet." But it was really important for her, this pilgrimage, especially as she was dealing with the death of my Grandpa.

And then when she passed away, I did the pilgrimage by bicycle in honor of her, which took about a month, because it's 750 miles. That's really far!

And so with the help of the Friendship Commission I was able to go back again later to research and interview folks from the pilgrimage community and get some more levels of depth about this Buddhist pilgrimage where people follow the footsteps of the monk scholar called Kōbō Daishi.

You get pieces in your books that reference Native Hawaiian history and mythology. You grew up hearing all these stories?

I did. I went to school at Mid-Pac in Mānoa where I heard a lot of the stories of Mānoa. So that's why even though I'm from Kapālama, I drew on that for the book. And when I was a little kid, I went to church school at St. Andrew's Cathedral, and a lot of the tutus [women elders] and aunties there would tell us stories about Hawai‘i, all the mo‘olelo [ancesteral stories] that they had grown up with. So, it was kind of part of my upbringing

Because you not Native Hawaiian, do you feel like it might be cultural appropriation if you wuz for incorporate one over abundance of Hawaiian elements into your poems?

Well, that's a really good question. That's something I struggle with a lot. So with the publication of both of the books, I thought, "Who am I to be writing these poems or sharing these mo‘olelo or referencing these elements of the ‘āina [land]?" And it's been difficult. I haven't come down to an answer. But I think in Ashore, I felt really strongly about having essays at the back of the book that accompany a lot of the poems to point to the ike Hawai‘i [Native Hawaiian knowledge] that I was inspired by and the people who held that knowledge. I want to honor that genealogy of knowledge so it's not just me appropriating, but more like I'm a product of these stories and here is more about where they came from and the people you can read if you want to know more about them.

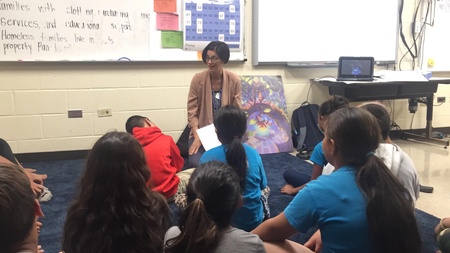

Seems like everyplace you lived you did lotta youth poetry workshops. Try talk about your work.

I started teaching poetry to kids when I was at grad school in Montana, so that's where I got some training. Then after that, when I was in Nicaragua, I helped to start a community arts organization that offered poetry, theater and visual art workshops to kids. When I went to Florida, I helped to start a writers in schools program offering poetry workshops and classes for children.

Back home in Hawai‘i, I've been teaching poetry in schools, through the Pacific Writers' Connection and then through the Artists in the Schools program with the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts.

What else you do besides poet-ing?

Now I do a lot of parenting. And I'm jumping into arts administration with my latest project.

I have been working on starting an ‘āina-based arts program called Hawai‘i Open Arts or HŌ‘Ā and we're just going to be launching our pilot this coming school year. In this program, elementary students work with a Teaching Artist and an Educator from a mālama ‘āina organization to learn about their home ahupua‘a and their place in it through outdoor, place-based art making and hands-on learning in the ‘āina.

You wen mention parenting. How has having keiki [a child] changed what you write?

Ever since my kid was born, I have been writing these things I've been calling sappy love poems to my baby. However the manuscript as of right now also has poems that are erasures of current events, especially erasures of news articles about climate change, disasters, floods, and fires. Writing these types of poems for this book has helped me kind of grapple with what it means to be a parent and see my child, my baby, who's now a toddler, come into this world that is so troubled.

With all da kine turmoil going on in da world, why does poetry matter?

You know, I sometimes wonder about that, too. I think that poetry is a way that I process the world and my place in it. I think about my grandparents' generation growing up in a depression and a war. And now we have the war in Gaza. We have the war in Ukraine. We have so many problems. And I think that poetry can help us touch into our humanity. Poetry can give us a space for reflection and inquiry that can help us become more whole humans.

© 2024 Lee A. Tonouchi