This story began as one of a series of narratives, for my children, about my life in the prospecting business. I wrote the tale some years ago about our encounter, as young teenagers, with the residents of Crow Creek, but so many questions remained in my mind about the settlement that I eventually decided that we must find out more. The result is this essay, which could not have been written without the aid of Bill Nakashoji and his wife Doris, and many others in the Kapuskasing-Opasatica area.

There are, of course, many other experiences related to the settlement which ought to be recorded for the public to see, and I hope they are. Already, too few people, even in the area, are even aware that it – and the expulsions that lay behind it – ever existed.

I hope that I have done justice to the story, and that you enjoy it. The responsibility for any errors (and one or two typos!) is mine.

* * * * *

I had a good friend in Swastika, named John Merrell. He and I often went on bush trips with our respective dads, who had been partners in a prospecting company in the late 40’s and early 50’s. Later, however, Dad joined Freeport Sulphur Co. as their Canadian exploration rep, and Larry joined the Brewis and White organisation.

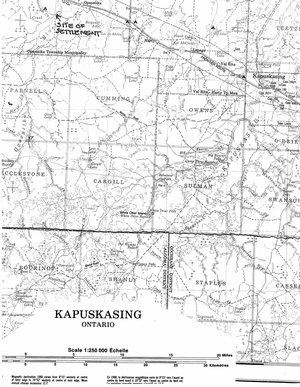

During a December (stretched) weekend in 1952, John and I got a chance to go with Dad, Jack Newman, and a crew of diamond drillers from Kirkland Lake to a property south of Opasatika, which is west of Kapuskasing, in northern Ontario, Canada. Dad and the drillers would be setting up the drill machine, while John and I were to do some chaining (measuring) of the picket lines on the grid surrounding the drill sites.

We drove to Opasatika from Swastika, and stayed overnight at the Opasatika Hotel, which was really a beer parlour with a few guest rooms. It had two-storey privy-style toilets, and I can still smell them.

An early breakfast, and we were off at first light to the Crow Creek property. It was very slow going – the road was rough, and there was quite a bit of fresh snow. The truck broke down several times, the worst of which was the result of a broken rear spring. John and I marveled at the ability of the drillers to make on-the-spot repairs, but still it was getting dark by the time we got to the camp. It’s a good thing we didn’t have to set up a tent ourselves.

Our quarters were satisfactory, and we had lots of good food – one advantage of winter work is that you don’t have to worry about fresh meat spoiling. And the job we had to do was not too taxing, even for us teenagers. So I think we were a bit disappointed to see the trip’s end approaching.

On the last day, John and I asked Dad if we could walk back to Opasatika, instead of waiting for a ride, which we already knew would be slow and rough. Dad had arranged for rooms at the hotel, and we would all meet up there. While the weather was cloudy, it wasn’t too cold, and we thought it would be a great adventure to undertake the trek.

Dad gave his permission, though he would probably have preferred that we wait and go out with him. He warned me that the weather could change at any time, and told us to stay on the road – no wandering around. After a late lunch, we packed up our gear for the truck to bring out, and started out the road. I seem to remember that we wore our snowshoes, since enough snow had fallen and blown onto the road that it was too hard to walk without them.

It was good going at first, and we made it more than halfway to the village in an hour and a half. Then it started to snow, gently at first, and then heavily, the snow in big wet flakes. The wind picked up till it seemed that the snow was coming almost horizontally at us, the way it appears when you’re driving a car in a storm. At times, we had to judge where the road was by feel as much as by sight. It gets dark early up there in December, and it was clear now that we were soon going to be walking in the dark, in the snowstorm.

We pressed on, pretty sure we were staying with the road, but nevertheless worried that we might stray from it, and mindful of the fact that going back to the camp was out of the question at that point.

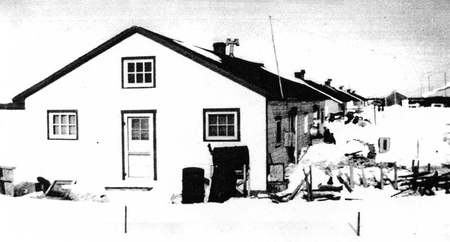

A while longer, and walking more slowly now, and totally covered with snow, we noticed off to our right, lights coming from the windows of a row of single-storey houses, banked with snow, just east of the road. They were quite unlike the big farmhouses that lay along the road south from the village.

We decided to drop in. Approaching them, we saw a small boy carrying a yoke with pails of water. We asked him where he lived, and he pointed to one of the buildings. We followed him to the door, and knocked.

The door opened, and what a sight greeted those outside and within! We saw a smallish room, lit by Coleman lamps, with hanging blankets apparently separating that room from others. And the place seemed to be full of Oriental people – men, women, children, more than we had ever seen in our whole lives. What they saw was less exotic but still a source of surprise: two strange, tall Caucasian teenagers covered – head to toe, the works – with wet snow, emerging from the middle of nowhere.

One man came forward, and welcomed us in English, and asked where we were headed on such a night. We told him where we had come from, and where we were going. When he reported this to those assembled, there was a lot of oohing and aahing. He told us we were quite close to Opasatika now, but that we could, if we wished, use their telephone to call a cab, to take us to the hotel. This sounded like a good idea. He offered us tea, but as I recall we declined, being a bit intimidated by the unusual scene we had stumbled into.

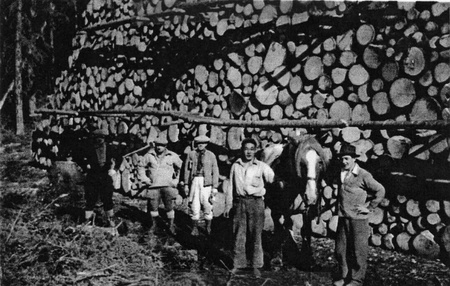

But our curiosity drove us to ask who they were and what they were doing there. The man told us that they were Japanese-Canadian families who had been moved away from the West Coast, after the outbreak of World War Two, and that the men were working in the forestry operations in the area.

We left shortly thereafter by taxi, and soon welcomed a bit of a bath and a warm bed at the hotel. We have talked many times since our meeting in 1952, about why those families were still there, in such an isolated spot, seven years after the end of the War. We learned, of course, that their British Columbia businesses and properties had been confiscated, and that they were prohibited for years from returning, but it was still a mystery – maybe, we thought, they were saving their earnings from the pulp camps to go back eventually to B.C. and make a fresh start.

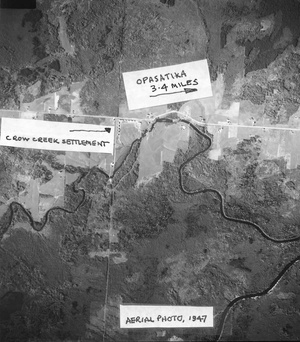

A year or so ago, John and I decided to try and get some answers to the questions that have been in our minds for some time, despite the passage of more than a half-century since our meeting at the camp, which we know now as “The Crow Creek Settlement”.

There is much material in books (both fictional and non-fiction) and the Internet about the expulsion of Japanese-Canadians from the west Coast in the early 1940’s. However, it deals primarily with either the big picture or the people in the western part of the compulsory movement. There is brief mention of the relocation centres (and the internment facility at Angler), in Ontario; and brief reference to the thousands ultimately moving on to employment and business opportunities in Ontario, but no specific references to the Crow Creek settlement.

The only hard piece of information we located in this initial phase was from a set of aerial photographs, which confirmed that the buildings were there in 1947, and gone by 1960. This was welcome confirmation that, at least, we weren’t making it all up!

We were also able, through friends, to speak to Japanese-Canadians who had been in one or more of the camps following evacuation, but no one was aware of Crow Creek. Nor did we receive anything specific from the National Association of Japanese-Canadians, in spite of getting in touch with them.

It was becoming clear that, if we were to have any chance of learning about Crow Creek, we needed to find the right people, Japanese-Canadian or not, still living in the area. And, sure enough, this led to our big breakthroughs. First, we were able to get from Ms. Julie Latimer at the Ron Morel Museum in Kapuskasing a copy of a letter that a Michi Ide had written to a student seeking information about the Crow Creek Settlement. Ms. Ide had been a teacher at the settlement, and her letter answered many of the questions we had, and raised other interesting questions requiring research. Unfortunately, Ms. Ide has passed away.

It seemed plausible from her letter that there might be other Japanese-Canadians still in the area, who had lived in the settlement. This prompted a search by John of the telephone directory for the northeast Ontario region, involving some 36,000 names. This yielded only two Japanese-seeming names – both Nakashoji. But, as it turned out, this was enough to produce our second, and biggest, breakthrough. It has allowed us to piece together, in microcosm, the story from beginning to end, and beyond, of the Crow Creek settlement.

And for this we are deeply indebted to Bill Nakashoji, for the information he (along with his wife Doris) was willing and able to provide, and the valuable local contacts he arranged – contacts like Alain Guindon, whose interest in local history and generosity in sharing it gave us valuable information and insights into the camp in its broader setting. And Bill and Alain led us to other sources, such as the 75th Anniversary book published by the Municipality of Opasatika – a magnificent tribute to the originating families of the area, and “recent arrivals” such as the Japanese-Canadians at Crow Creek.

© 2016 George Tough