Defending Japan’s Position

Regarding his own position as a Japanese American, Tashiro explained, “As a Japanese American standing between two countries, I would like to promote friendship in and for both countries. Regarding the present Sino-Japan conflict, it is the duty of Nisei to explain the background and rationale for the conflict, in order to prove how right Japan is and to correct the misunderstandings of certain Americans. How can we convince others if we are irresolute ourselves? As Japanese Americans, the Nisei should be 100 percent behind Japan’s position.”1

The passionate way Tashiro defended Japan’s position in China in such talks was described by Takayuki Asano, his former teacher, who visited him in Chicago. He commented on Tashiro to a newspaper reporter as follows:

Isamu has worked very hard to introduce Japan to America and when he meets a person who criticizes Japan, he tries to argue with and persuade the person until the person is convinced. He is doing so much good for Japan. One day a white man visited him and blamed Japan for its policy for Korea. Isamu argued with him for more than an hour. You can see how enthusiastic he is to introduce Japan to America. To me his filial duty is amazing.2

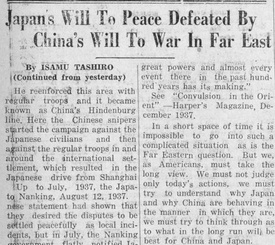

In his talks on political matters, Tashiro was confident enough to say that “[i]t was this will to war on the part of China which defeated Japan’s will to peace in the Far East.” He continued,

But we, as Americans, must take the long view. We must not judge only today’s actions. We must try to understand why Japan and why China are behaving in the manner in which they are, we must try to think through as to what in the long run will be the best for China and Japan. This whole problem needs the thought of the best minds. A solution will not come through condemnation nor quarantine. The facts are available; we must inform ourselves, and prepare ourselves to face them. As in our local community, we investigate scientifically the causes which underlie anti-social behavior, so must we learn to act in the world community if peace is to become a reality.3

However, most American audiences were bewildered by Tashiro’s forceful vocabulary, spoken in perfect English, especially when he insisted that Americans should stand up for justice and support Japan’s use of military force to discipline the Chinese military whenever they violated international ethics.4

Fighting Slander Against Japan

His vigorous activities in Japan and lecture series in the U.S. attracted attention from the Japanese media. According to an Osaka Mainichi article, Tashiro commented to a reporter that “he was Japanese, Japan’s suffering was his own suffering, and he wanted to do his bit for Japan.” According to the article, Tashiro was fighting fearlessly in the U.S. against unfair slander toward Japan.5

When the second Sino-Japanese War started with the Marco Polo Bridge incident in July 1937, Tashiro could not stay silent. He returned to Japan in August 1937 to collect verifiable information about Japan’s claims against China. He visited the army, the navy, the ministry of foreign affairs, and the ministry of national railways to hear their stories. He then hurried back to the U.S. in August to deliver lectures on what he learned, exposing the misery of the China situation to his American audience. With the completion of a new film, his schedule was filled for the next six months, until the following spring of 1938.6

Tashiro’s project was well-received by the Japanese government and its subsidiary agencies, the US–Japan Association, and big business entrepreneurs such as Takashi Masuda and Kokichi Mikimoto.7 The ministries of foreign affairs and national railways even offered to make him an ad-hoc employee. However, Tashiro declined the offer with the excuse that his activities were his hobbies, not his vocation.

Tashiro told a reporter humbly that he was not doing anything worthy of being reported in the press, but he wished that even just one person living overseas, like himself, could somehow help Japan.8 Tashiro’s humble attitude must have been one of the reasons that Tamotsu Murayama, a Nisei journalist, called him “the top Nisei Champion of Japan–US relations.”9

Working as an FBI Informant

Even while he was working so hard to promote Japan to Americans, around 1937, Tashiro started visiting the FBI office in Chicago. The trigger for these visits might have been when a group of African Americans from Detroit, who called themselves the Development of Our Own, came on a goodwill mission to the Japanese Consulate in Chicago on October 9, 1937. The visitors explained that they were impressed by Japan and interested in learning more about Japan from the Consulate.

As a result, the Japanese Consul sent Tashiro to Detroit to lecture on Japan and the Japan-China conflicts at the Development of Our Own’s October 17th10 meeting. This group was a radical anti-government organization established by Japanese national Naka Nakane, aka Satokata Takahashi.11

According to Tashiro’s report to the FBI, the “invitation (to the talk in Detroit) was extended by Mrs. Takahashi (a black woman) and the organization paid his transportation expenses to the meeting in Detroit and offered him an honorarium, which he declined.”12

Development of Our Own had been under the surveillance of the U.S. government for a long time. It may be that Tashiro, who previously knew nothing about the group, received an order from the FBI to watch the group and report on their activities. Tashiro reported on October 2, 1942 that “members of the Development of Our Own from Detroit, Michigan have visited the Japanese Consulate in Chicago, and have made … contributions to the Japanese Consulate.”13

Interestingly, the same FBI report recorded the following as well: “It should also be mentioned that Dr. Tashiro has been the subject of numerous complaints to this office questioning his loyalty to the United States. In further evaluating the information furnished to his office by Tashiro, it is well to note that on several occasions he has appeared in the Chicago office to furnish information on Japanese activities and in most instances his information has been found to be reliable.”14

We may never know what other kinds of activities within the Japanese community Tashiro reported, or what might have been his motive “to furnish information on Japanese activities” to the FBI.

Notes:

1. Kashu Mainichi, September 10, 1937.

2. Hawaii Hochi, July 22, 1930.

3. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, July 17, 1938.

4. Kashu Mainichi, September 10, 1937.

5. Hawaii Hochi, September 3, 1937.

6. Nippu Jiji, October 7, 1937.

7. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, October 14, 1936.

8. Hawaii Hochi, September 3, 1937.

9. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, February 21, 1935.

10. FBI Report 65-562-53X; Nichibei Jiho, October 16, 1937.

11. Takako Day, “Suspicious Points of Contact in Pre-War Chicago: The Japanese Consulate and Naka and Pearl Nakane,” Discover Nikkei

12. FBI Chicago Report dated April 11, 1944.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

© 2024 Takako Day