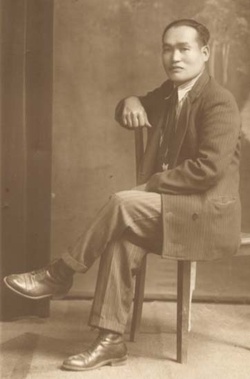

Every afternoon my father, Tatsuzo Tomihisa, sat on the sidewalk in the doorway of our house. He observed the street in silence, but the kids from the neighborhood came to see him right away, as if they’d been waiting for him. He greeted them with a smile, since he loved children and he patiently shared all his stories with us.

Because the land of his birth was so far away, we all wanted to know how he had crossed that enormous ocean. He generously shared the exciting anecdotes stored in his memory.

We listened quietly, waiting for his memories to flow, and then we’d laugh, feel sad, and even scared as he told us about his adventures. We were grateful to have a minor part in those stories; his narration was so vivid it shook our souls and we felt like we were part of that wonderful experience. Sometimes he became serious, and during those silences we sat by his side, holding our breaths and waiting for him to overcome that difficult circumstance and share his life stories with us once again. Wide-eyed and pulses racing, we anxiously awaited each story, knowing we’d travel through the universe and conquer the world.

I remember one story in particular. After a long journey, he had disembarked from a boat in Peru. Not knowing where to go, he began walking into a wild jungle filled with strange sounds and smells, and he sensed that animals were hiding in the thick vegetation. After a long trip, he was desperate to find a place to spend the night and he began walking faster, as dusk’s shadows hurried him along.

Just then he heard a strange shriek and turned around and saw an enormous wild boar coming towards him. Since he knew these animals were very aggressive, he sped up to put some distance between them, but the animal also began moving faster and he had to run as fast as he could. He decided to climb a tree and dropped the bag holding the few possessions he owned. He climbed up a leafy carob tree to reach safety on a forked branch, resting there while he listened to the agitated breathing of the beast, its shrieks continuing with every exhale. Impatient and aggressive, the boar bared its sharp fangs, and even stood up on two legs, smelling the trunk of the tree where my father was hiding. Many hours later, the exhausted animal lay down next to the tree while my father watched it, terrified and knowing it wouldn’t be easy to escape this stalker.

After dark, the boar fell asleep snorting and Father, who was also very tired because he’d been walking since morning, rested in the branches. When dawn pushed a faint ray of light through the vegetation, my father opened his eyes and saw the boar, unmoving and still in a deep sleep. Seeing that this was his only opportunity to get out alive, he very carefully climbed down the other side of the tree and as soon as he touched the ground, he took off running like never before. He ran away up a slope that abruptly ended at a beach, where he quickly jumped into the water. It didn’t look as if the animal was following him, but he didn’t stop and kept on swimming to the opposite shore. It was only then did he realize he’d forgotten his bag, with the only possessions he had. But he had no regrets; it was a small price to pay to save his life. He kept walking in search of a village, eating wild fruit and taking short rests, until he finally found some mud huts inhabited by brown-skinned people who spoke very softly. He had arrived in Bolivia, and was very close to his final destination: Argentina.

But my father was still a nostalgic immigrant who wanted only to put down roots and maintain his large family with his own earnings. Events occurring around the world created a very difficult situation for him here; he felt rejected by the society in which he had decided to build a life. In the 1950s, there was a strong pro-Yankee attitude in our country and he couldn’t find a job. He’d been trained to cut hair, but even though the only hair salon in our neighborhood was always full with customers, the owner refused to hire him.

Japan had lost a bloody war and Argentina joined in the American euphoria. Japanese immigrants were rejected as if they had also died in the ashes of destruction in the country of his birth.

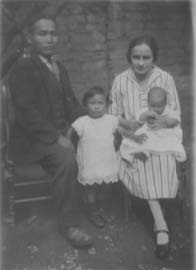

Father, with his infinite patience, accepted his marginalized status and took a job washing clothes in a relative’s laundry. Eager to earn more, he also made nets and weights for fishing that he then sold. He built a chicken coop filled with chickens, and we sold the eggs all over the neighborhood. But we had many needs and his income wasn’t enough, so when my sisters were teenagers they had to go to work. This deepened Father’s depression; his masculine pride was wounded.

From then on, he experienced an inevitable physical decline, and only told sad stories about people who’d lost their struggles, crushed by the obstacles they faced. There were no more courageous victors, or fabulous paradises discovered by noble people fighting for a dignified life… My father was defeated, without ever having picked up a weapon.

* * * * *

Our Editorial Committee selected this article as one of their favorite Nikkei Family stories.

A Comment from Enrique Higa:

While I was reading “Father’s Adventures,” I felt as if I were one of those neighborhood kids sitting and listening to him tell stories, fascinated by his tales of a life full of excitement. When Tatsuzo ran away from the boar, climbed a tree for safety, and later jumped into the water, I felt as though I were watching a movie, holding my breath and hoping the animal wouldn’t reach him. Even though life wasn’t easy for him after that, I’ll stay with the image of this daring immigrant who crossed the ocean, endured difficult conditions as he traveled through several countries, and survived the jungle, as only the brave can, to secure his future. A moving tribute to Father.

© 2015 Marta Marenco

Nima-kai Favorites

Each article submitted to this Nikkei Chronicles special series was eligible for selection as the community favorite. Thank you to everyone who voted!