Percussion is probably the oldest musical instrument in human civilization. In fact, it is older than written language. In Yoruba Land in Nigeria, for example, drums have been used as speech surrogate for thousands of years. Dundun, or talking drum, could be heard from as far as two miles away. With a relay system, the Yoruba people used talking drums as an important means of telecommunication long before the invention of modern technology.

Taiko, or “big drum” in Japanese, also has a long history. Along with other cultural artifacts, taiko most likely traveled from the Asian continent with the migration of people. Taiko can be found in archaeological sites from as early as the Joumon Period (10,000 B.C.E. – 300 B.C.E). Excavated earthenware drums and clay figures that depict drummers suggest that drums were used on ceremonial and religious occasions in ancient Japan. Taiko’s use as a spiritual instrument continued over time. Primarily a farming people, the Japanese have used taiko in festivals and rituals to pray, give thanks for good harvests, and keep away misfortunes. Obon, the Buddhist summer festival, was a particularly important occasion in which taiko was played. At the Obon dance, or Bon odori, people danced, circling around a yagura (wooden platform) where a singer, a drummer, and a fue (bamboo flute) player provided background music for dancers. Traditionally, only specially assigned people were allowed to play taiko on specific occasions, using specific patterns. Each village had its own rhythm patterns, which were carefully protected and passed on through generations. Many villages in Japan still preserve these patterns, although some patterns have transcended village boundaries and become nationally, or even internationally, well known. This, however, did not happen until after World War II, when taiko’s social function changed dramatically.

Despite its long history as an instrument, taiko as we know it is a post-World War II phenomenon. Taiko became performance music after Daihachi Oguchi, a jazz drummer from Nagano Prefecture, put multiple drums of different sizes side by side and played them together. Osuwa Taiko, Oguchi’s group, started performing in 1951. Several years later, Seido Kobayashi, the winner of the Tokyo Obon Taiko Contest, started O Edo Sukeroku Taiko. Osuwa Taiko and O Edo Sukeroku Taiko became professional performing groups, and were instrumental in developing taiko as popular performance music. This was the start of taiko’s presentation as performance in non-religious, non-ritualistic spaces, such as concert halls, community centers, department stores and beer gardens.

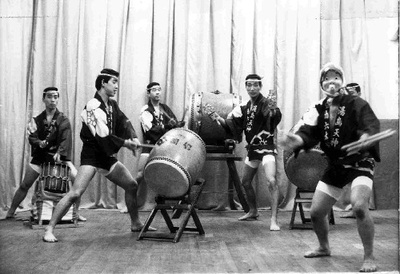

A Performance by O Edo Sukeroku Taiko at the early period (The early 1960s). Funabashi Health Center, Japan. Courtesy of O Edo Sukeroku Taiko

In North America, taiko existed as early as the turn of the 20th century within the Japanese immigrant community. In Hawai`i and on the West Coast, Issei (first generation) organized Bon odori. It was one of the forms of community entertainment that immigrants, who were mostly of working-class backgrounds, remembered from their home country. Obon and Oshogatsu (New Year’s festival) were the only two breaks that working-class people could enjoy back in Japan. Life was also difficult for working-class Issei in the United States. Bon odori provided Issei with not only entertainment but a chance to gather and reinforce their sense of belonging to an ethnic community. Documents, photographs, and even rare home movies provide evidence that Japanese Americans celebrated Obon—complete with taiko players, yagura, and dancers—during their World War II incarceration in America’s concentration camps.

© 2006 Masumi Izumi