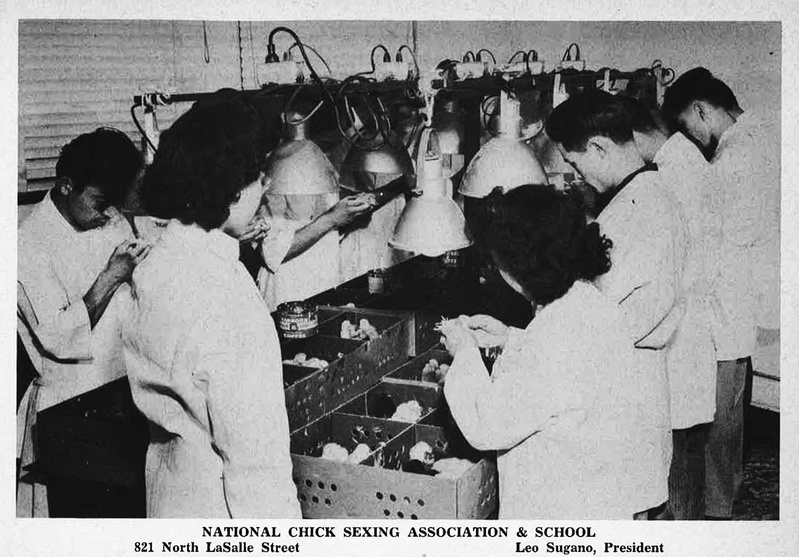

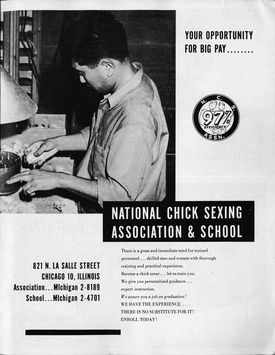

At modern-day 821 North La Salle Street, in the River North neighborhood of Chicago, few people today could possibly imagine that here at this site was one of the main Japanese American chick sexing schools outside of the west coast. Indeed, at the site of the upscale apartment building that now marks this space, one can find few traces of a business that used to permeate the very fabric of this neighborhood with the smell of burnt chicks.

“They disposed of the used chicks in an incinerator in the back of the building,” said Jimmy Doi, who in the early 1950s attended the National Chick Sexing Association School that used to occupy this space. “And on occasion, there were complaints of the odor from the neighbors.”

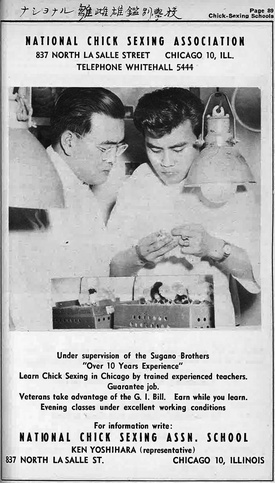

The National Chick Sexing Association and School was founded in the immediate postwar period by George and Ann Sugano, and was run with assistance from George’s brothers, Mark, Steve, Leo, Frank, and Tomio. Patti Sugano, daughter of George and Ann Sugano, remembers well that the smell of the school incinerators could often bring unwanted attention.

As Patti related, “I remember my mother telling me that somebody called the police, because they thought they were burning bodies in the building, because the way the chick sexing goes is that the females lay the eggs and are more valuable, so the young chicks that were males would just have to die and go in the furnace.”

A Japanese American Ethnic Enterprise

Chick sexing entails the differentiation of male versus female chicks in the immediate days after being hatched, in order to cull the male chicks and preserve the female chicks. Since female chicks were desired because they could lay eggs, chick sexing could help to guarantee for egg producers that their feed would only be used for egg-laying hens instead of being wasted on non-egg-producing cockerels.

Specific methods of chick sexing had been developed in Japan as a specialized skill, and were introduced to the U.S. through the work of Japan-trained chick sexers, who helped popularize the trade.

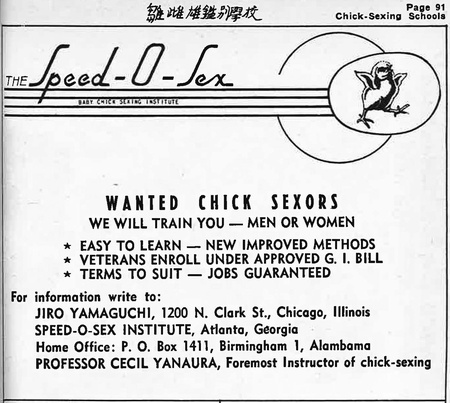

Aside from the National Chick Sexing Association and School, there was another short-lived Japanese American operated chick sexing school named Speed-o-Sex, which was based out of Atlanta, Georgia, and had a 1200 N. Clark Street office in Chicago managed by Jiro Yamaguchi. Existing records suggest that this branch office was short-lived, and most likely closed by 1948.

(Collection of the Japanese American Service Committee in Chicago)

Further south of Chicago, in central Illinois, Joseph Igarashi was the western branch manager of the American Chick Sexing Association (“Amchick”) in Nokomis, Illinois, which practiced a slightly different vent sexing method than the Chicago school. Pioneering chick sexer John Nitta had founded the organization in 1937 with its home offices in Lansdale, Pennsylvania.

Due to their homeland connections, Japanese Americans were able to enter into and gain a virtual monopoly in the U.S. chick sexing industry, accessing an occupation that provided much needed, lucrative seasonal employment opportunities despite job discrimination and glass ceilings at large.

“I think it was more of a Japanese profession because of the skill of it, and though it was more of a dirty job, they would teach Japanese nationals how to do the chick sexing,” noted Patti. “Most if not all of the work was done in rural areas, in places like Indiana, Nebraska, and Kansas. I remember my parents being gone for most of the week, because they would go to Indiana whenever the chicks would be hatched.”

Roy Akune, who had been trained at the school in Chicago, and who had worked over a decade as a chick sexer, explained the difficulties of this occupation.

“You had to work long hours, sometimes up to twenty-four hours without sleep, because you had to finish. You had a contract with a chicken hatchery, so you had to go around and after you finished at one place, you’d stop to rest and order a sandwich, and you’d be eating while you’re driving, and go to the next destination.”

Tight deadlines were integral to the work, in part because it became more difficult to assess a chick’s sex as they got older.

As Roy noted, “Once they get older, then it’s harder to determine their sex. You had to look at a chick within twelve hours and if you go over that, then it’s very hard, because the color would change and you’d make more mistakes.”

“The female organs were shinier, like how a moon shines. The male organs had a dull color. You had to learn that, so it would take a long time to be a professional chick sexer.”

© 2016 Ryan Masaaki Yokota