It was early in the morning of March 11, 2011, and Midori Suzuki was having trouble sleeping. That same day, the Japanese Mexican Association was to inaugurate an art exhibit called Flor de Maguey that she had organized with some of her fellow painters. After Midori was finally able to fall asleep, a friend called to tell her there had been a massive earthquake in Japan. Still not totally awake, she answered quickly:

“Don’t worry! It’s probably just one of those earthquakes that always happen in Japan,” she said and hung up.

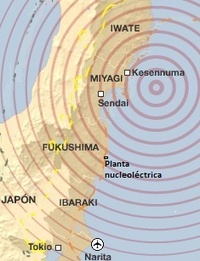

But her daughter woke Midori up early and showed her images on her laptop of the tsunami and the devastating 9.0 earthquake that had caused it on the coast of the Tohoku region in northern Japan, where Midori’s mother lived. The images said far more than words. Midori was in shock; she couldn’t believe her eyes, and for an instant she thought it was just a nightmare. She immediately grabbed the phone and called her mother, who lived in the small city of Kesennuma, in Miyagi Prefecture. No one answered the phone. Nor was she able to reach her sister who lived nearby her mother, and calls to several friends also went unanswered. Suzuki realized that she wouldn’t get any information that way.

News and images began flooding in from social media, and like a tsunami they took over the news programs on TV and radio. Midori was upset and terrified: Although her mother lived in one of the highest parts of the city, her sister’s apartment was close to the ocean.

Unable to eat breakfast, Suzuki went to the Association’s Cultural House to open the art exhibit she’d been preparing for months. The paintings were already mounted, ready to be admired by the public awaiting the show. But no one talked about the paintings; the only topic of conversation was the earthquake and tsunami. To the dismay of all present, news arrived about another disaster on top of the calamities caused by the earthquake and subsequent tsunami: an accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. One of the reactors had been severely damaged and the coolers of the other reactors failed, and as a result all of the inhabitants within 20 kilometers around the plant were evacuated to protect them from the risk of nuclear radiation.

When the exhibit opening was over, Midori’s students and others present gathered around her to provide words of encouragement and hope. Despite all her anxiety, the only thing that crossed her mind was how to help her compatriots. Midori and the other artists in the show took the empty box of cookies they had shared with their assistants and began asking everyone present for donations. Soon the box was too small to hold all of the bills and coins that were so generously donated. That must have been one of the first donations among the thousands sent from Mexico!

The following days were very difficult, since Midori still had no news about her mother. What little news that did arrive wasn’t very hopeful, since the damage caused by the earthquake and tsunami was enormous. The number of dead and disappeared was already in the thousands, but Suzuki never imagined, as we now know, that the Miyagi Prefecture was the hardest hit. In total, close to 20,000 people died and more than 400,000 buildings and homes were destroyed.

In the weeks after the earthquake, almost 4.5 million people remained without electricity and 1.5 million had no water supply, according to information from the Japanese authorities. The state channel NHK broadcast news day and night, and Suzuki watched it constantly. The painter found no consolation, however; the bad news kept coming, minute after minute. Because of the radiation leaks from the Fukushima nuclear plant, the water and food in that prefecture and adjacent prefectures could not be consumed.

Midori couldn’t picture the towns and cities destroyed as they had been along the coastline of the hardest hit prefectures of Tohoku (Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima). She also found it hard to believe that the ocean, which had provided such a beautiful backdrop to her childhood, was the source of the most terrible images of her beloved city of Kesennuma. She remembered that when her parents had returned from Manchuria at the end of the Pacific War, a time when the only abundant thing in Japan was hunger, that same ocean had provided them with sustenance and work. When Midori was a girl, the ocean was where they obtained the most delicious treats she’d ever tasted: katsuo fish (bonito) and sea urchin, as well as algae such as nori, konbu, hijiki, and wakame. That’s why she refused to believe that the ocean was now capable of devouring many of the region’s fishing villages.

Over the next two weeks, telephone service was still cut off and Midori was unable to reach her family. She spent her time watching the news and organizing events to support the victims in Japan, which included not only those battered by the telluric force of the earthquake and the 40-foot waves of the tsunami, but also the more than 45,000 displaced people living within 30 kilometers of the nuclear plant.

Despite suffering enormously as she watched all the pain and destruction on the news, Midori could not tear herself away, hoping to receive some information about her mother and siblings or at least to find out the condition of their neighborhood. In addition to the news, the TV stations broadcast a series of reports on the situation of those affected in Kesennuma. On one of those programs, the reporter asked permission to enter homes in order to interview survivors. Suzuki was greatly surprised to see her 85-year-old mother open the door to her house and invite the reporter in. She couldn’t believe what she was seeing and called to her daughter to confirm that the woman on TV was indeed her grandmother and that she was fine. During that TV program, Midori also found out that the family of her youngest sister Kazue was living with her mother because their home had been covered by water and mud.

Knowing that her family had survived gave Midori the strength to continue organizing and supporting those affected by the earthquake and tsunami. These activities involved not only the Nikkei community: The solidarity of the Mexican people was overwhelming. In particular, Midori was profoundly moved by the donations of young people in secondary schools who contributed what little they had to help her suffering compatriots. This gave her the motivation to continue painting.

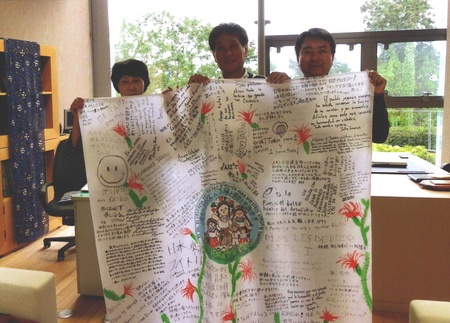

Midori wondered how she could bring all of that affection and support from Mexico to the victims; money wasn’t capable of sending that message. In May, two months after the earthquake, she traveled to Japan, taking with her 12 blankets she had painted with Mexican flowers and dolls. There were also messages in Spanish of affection and encouragement to the victims; these messages were translated into Japanese. Upon arriving in Kesennuma, she organized visits to several primary schools and local government offices, where the blankets with their messages of support from Mexicans to the students and citizens of Miyagi Prefecture were exhibited. One of the many encouraging phrases written on the blankets said: “We Mexicans are with you in the most difficult of times.”

In addition to the blankets, with the help of a Mexican Nikkei family who lived in Japan (the Takedas), Midori made Mexican piñatas that the children broke open at the schools. Her visit had two goals: first, to explain Mexican traditions and share stories of Japanese emigration to Mexico, and second, to allow the children to relax and enjoy a popular custom among Mexican children and provide them with small gifts. Midori took with her not only the funds donated by thousands of Mexicans—the money was given directly to the victims—but through her art she was able to transmit the solidarity and affection of Mexico’s people toward the Japanese, at a time when they needed it most.

© 2017 Sergio Hernández Galindo