“50 Objects/50 Stories of the American Japanese Incarceration” is a project made up of 50 objects that each give a raw, true narrative of the exclusion and confinement of 120,000 American Japanese during World War II. Objects owned by families, museums, and educational institutions have been researched, reviewed, and compiled to create a well-rounded representation of individual experiences in the internment camps. Stories that have gone untold for years are now presented in various forms of media such as articles, videos, and audios.

I interviewed Nancy Ukai, the Lead Project Director, to learn about her creation and overall message of “50 Objects/50 Stories,” as well as her opinion on its imminent relevance to our society today. The project is sponsored by a grant from the Japanese American Confinement Sites program of the National Park Service.

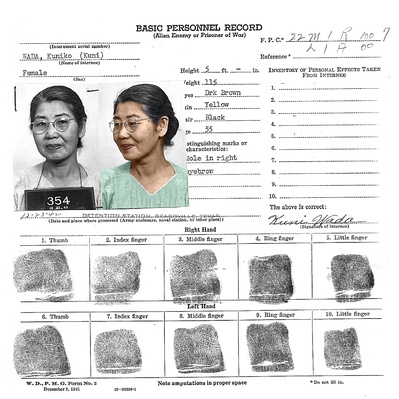

To give a bit of a background, the project defines “object” broadly and includes texts, photographs, 3-D artifacts, and landscapes. Even a collection of many items qualify because “things like people often come in groups due to the conditions under which they were made or preserved.” Their definition ensures that no story becomes lost or untold.

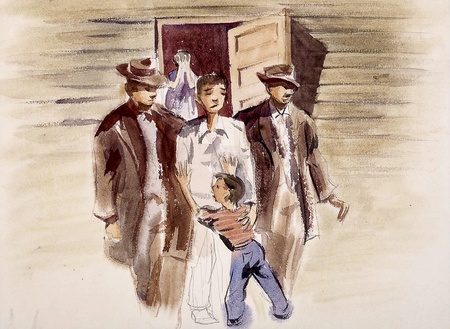

“50 Objects/50 Stories” aims to extract personal stories from objects to preserve its history in a unique light. Nancy Ukai explains that so much personal cultural property was lost during the war because things were sold, burned, discarded, stored, and stolen before internees were sent away. Once they were in the camps, objects were made out of necessity and simple things took on great value. She recalled reading about a wedding gift in one of the camps that consisted of used nails. She emphasized the fact that objects do not speak, so one must do their own research of the migration and personal association of objects.

Nancy Ukai’s inspiration for this project stemmed from a radio program on BBC titled, “A History of the World in 100 Objects,” which examined 100 artifacts from the British Museum collection to tell a two-million-year-old history of humanity. Drawing from this idea, Nancy Ukai wanted to collect tangible objects to explore and tell the story of American Japanese incarceration throughout the various camps. She believes that telling the story through the form of social media would be most effective due to its relevance to our present society. Other team members also effectively contribute to the storytelling. The art director, David Izu, creates his own language and style of visual storytelling using family photos, documents, and object images. The filmmaker, Emiko Omori and Kimiko Marr, have created short videos for some of the modules.

One must wonder how Nancy and her team were able to choose only 50 objects to tell a story that was so unique to thousands of people’s experiences. Nancy Ukai explains that their team of academic advisors gave feedback and recommendations on an early list of roughly 80 objects that they had previously compiled. These were found through intensive research, speaking to a vast majority of many people, and browsing through museum and family collections.

Her group’s goal was to have a range of items that were compelling as unique objects and carried intriguing stories. For example, two of the fifty objects avoided private auction by grassroots activism. These two objects were a barrack chair made at Heart Mountain and an extraordinary pair of Bibles, which were exquisitely illustrated and transcribed by an immigrant man while he was confined at Poston.

Another object, a pair of Japanese geta wooden sandals with painted Mickey Mouse figures, was painted by an immigrant father who was arrested for being involved with kendo fencing. He was separated from his family for two years and made the geta for his son, who was in a different concentration camp 600 miles away.

When asked which object stood out to her the most, Nancy found all of them intriguing, but felt a sense of wonder about a gold pocket watch that was given to an immigrant man by his white employer:

“The man, Wasuki Hirota, had worked for a citrus firm in Azusa, California, for 38 years and had married a U.S. citizen who had Native American and Mexican ancestry. They wed in Tijuana because interracial marriages were illegal in California. They had five children who were sent with him to Santa Anita because they were half Japanese, but the family was separated when the children and the mother were allowed to go home.” Great efforts were made to release Mr. Hirota but he passed away at Heart Mountain without seeing them again. The descendants still have the gold pocket watch which their ancestors had carried to three camps. It still runs.”

Through this project, Nancy hopes viewers will learn that objects are deeply engraved in each and every one of our family’s histories, and should therefore be treasured and preserved. She shares three pieces of advice to readers:

- Don’t throw away the objects, especially letters and documents, which are evidence for this period of history. If you find letters or other handwritten documents in Japanese and cannot read them, please help preserve them for the precious details they may provide about the lives of our Issei ancestors.

- If your family has living survivors from this period, take your phone and interview them. If they don’t want to talk, open up a photo album and ask them to start talking about the people on the pages. Write down the names, too.

- Although it is hard to face, we must not forget about the trauma and dislocation that our ancestors suffered. Please assemble their family histories before all the memories are gone. You can request your family member’s individual WRA case files from the National Archives. These may hold surprises. The incarceration left a legacy of shame, generational trauma, and division, but also of resistance, strength, and resilience. By learning about historical objects and understanding their contexts, some of the puzzle pieces of family and community history can be put together and provide some coherence.

Nancy Ukai shares that this project has opened her up to the complexity of American Japanese history and the depth of its history. Although she has dedicated much of her lifetime’s work to this area, she still learns something new everyday. By constantly educating oneself in the history of Japanese Americans, Nancy Ukai explains how “one gains a deeper understanding of our country’s history and how it has been a story of repeated detention, deportation, and family separation of a succession of peoples of color. Japanese Americans are only one group of many who have suffered, both as immigrants and as citizens, because of racism - the “defining factor” in U.S. history.

About Nancy Ukai

Nancy Ukai grew up in Berkeley during the 1960s and witnessed the beginnings of the Ethnic Studies Movement. Along with the movement and her mother’s incarceration experiences, Nancy grew a strong interest in the subject of Japanese Americans and expanded on her studies in college through Asian American studies. She became involved with the community at 15 years old providing relief services to activists in Alcatraz and continues to contribute through active engagement with the Rago auction in 2015 and the Topaz Museum.

* * * * *

To learn more about Nancy Ukai and the “50 Objects/50 Stories” project, please visit their website. If you would like to learn more about the history of American Japanese incarceration during WWII, feel free to take a look at Nancy Ukai’s other project, Tsuru for Solidarity.

© 2019 Kate Iio