When I attended college at UC Riverside closing in on five decades ago, I took a sociology class on Japanese Americans and World War II. Like many Sansei, I knew very little about my family’s experiences during the war, but I was stunned at the enormity of the events that swept up our Japanese American community. After being rebuffed by my mother to share her memories of camp, I went to the college library and was dismayed to find how little scholarship existed on the forced removal and mass incarceration of 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry almost 30 years after the fact.

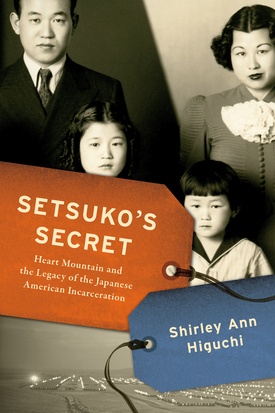

What my 20-year-old self could have used at that time is Shirley Ann Higuchi’s recently published book, Setsuko’s Secret: Heart Mountain and the Legacy of the Japanese American Incarceration. Exhaustively researched while remaining personal and frank, Setsuko’s Secret is both an informative summary of Japanese American history and an autobiography. One rough comparison is if you had merged Michi Nishiura Weglyn’s groundbreaking Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps with Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s landmark Farewell to Manzanar, two pillars of Japanese American history from the 1970s.

The book’s title is a reference to Higuchi’s mother Setsuko and how Shirley and her brothers were surprised when their dying mother indicated that she wanted any koden money received from her funeral donated to the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation (HMWF). Shirley had never heard of this organization and was shocked that Setsuko was a major donor to help build a museum at the site of the Heart Mountain concentration camp where her parents had met during World War II.

As with me, Shirley had once asked her mother about life in camp because of a college class when she was a student at the University of Michigan (where her father William was a professor of pharmaceutical sciences), only to get into an argument because Setsuko angrily insisted she was happy in camp. Growing up in Ann Arbor, Michigan, away from other Japanese American families, Shirley had never before questioned her parents’ unwillingness to share their experiences, happy and sad, about being imprisoned with their families during the war.

“Although my mother never talked about the negative experiences of incarceration, I instinctively knew that something bad had happened to my parents and grandparents,” Higuchi writes in her book. “Something about it seemed as if she were covering a deeper damage, but I couldn’t put my finger on it.”

After her mother passed from pancreatic cancer in 2005, Higuchi was invited to Heart Mountain for the dedication of a walking trail named for Setsuko. Accompanied by her son Bill, Shirley met a whole community of people dedicated to preserving a chapter of history that her parents had not shared with their children. Among them were then-Secretary of Transportation Norman Mineta and the individuals who ran the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation led by Doug Nelson and Pat Wolfe. Asked to complete her mother’s term on the HMWF Board, Shirley agreed and, as she wrote, doing so opened “the door to my history and to truly define who I was.”

Higuchi, who was working successfully as lawyer in the Washington, D.C. area, came to the realization that she needed to catch up with the rest of the board on the core history about the war and the Heart Mountain camp. But just as important, Shirley found her directness and cultural style differed greatly from the other Japanese Americans who grew up in larger Nikkei communities. Eventually nominated to become the board’s chair (which caused its own turmoil), Higuchi discovered that in order to fulfill her mother’s dream, “I became steeped in the complexity of a community that has been fractured and divided for almost eighty years.”

The result is a book in which the author seeks to better understand her parents and their experiences by taking a deep dive into Japanese American history, beginning with tracing several families back to Japan. Higuchi keeps her history from devolving into a lifeless trek by following the stories of her parents’ families along with concise interspersed summaries on the lives of the famous (U.S. Senator Daniel Inouye and Norman Mineta) and the less well-known (Clarence Matsumura, Takashi Hoshizaki, and Raymond Uno). It is notable that Higuchi includes not just a glossary of terms and 30 pages of end notes, but almost 10 pages of a list of “Cast of Characters.” While historic events are prominent, Setsuko’s Secret is a book about people.

Being a good lawyer, Higuchi is thorough about the presentation of her evidence, especially on historic events. She describes in detail the circumstances leading up to and just after the issuance of Executive Order 9066 that led to the authorization of the forced removal of all persons of Japanese ancestry. What is made clear in the book is that the government had ample indication at that time that Japanese Americans were not a threat to national security.

Higuchi points to Lt. Commander K.D. Ringle of the Office of Naval Intelligence, who was charged with assessing the situation. He wrote that the “entire ‘Japanese problem’ has been magnified out of its true proportions, largely because the physical characteristics of the people.” Ringle felt rounding up the entire population made no sense when things “should be handled on the basis of the individual, regardless of citizenship, and not a racial basis.” But government officials succumbed to hysteria and, as Higuchi explains, political expediency, resulting in thousands of innocent families’ removal from their homes.

Higuchi describes the most tumultuous community issues through her characters. The role of Mike Masaoka, executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), is laid out plainly as the source of long-standing ire from those imprisoned. “The (JACL’s) leadership believed it was inevitable that the government would force Japanese Americans to move, so resistance would be futile,” Higuchi explained. “(Masaoka) willingly traded away the rights of Japanese Americans in the name of shared sacrifice, which he, as a resident of Salt Lake City, Utah, did not have to make. He lived outside the exclusion zone.”

This created great anxiety for the Mineta family when Norm’s older sister Etsu married Masaoka in 1943. Inmates who blamed JACL for its role in the forced removal smashed the windows in the Mineta family’s barracks. “All the windows in our barracks building unit were broken out because people threw rocks at the window to tell us the message,” Norm recalled. His father Kunisaku was able to get a job in Chicago and soon left camp. In November of that year, Norm and his mother followed.

Higuchi provides an overview of another troubling issue through the story of a young Takashi Hoshizaki as someone caught in the controversy surrounding what became known as the loyalty questionnaire. “Although the military and the WRA (War Relocation Authority) intended the questionnaire to make it easier for incarcerees to join the Army or relocate to cities across the country,” Higuchi observed, “its overall effect was to heighten the tensions within the camps and to bring more unwanted scrutiny from politicians who had never considered the best interests of the Japanese Americans.”

Specifically, Questions 27 (which asked if individuals were willing to serve in the Army for combat duty) and 28 (which asked individuals to swear allegiance to the U.S. while forswearing allegiance to the Emperor) resulted in confusion over the poorly worded queries and led to a new description of a dissident: “No No Boy.” Teenage Takashi Hoshizaki gave a “qualified no” to Question 27, adding he would serve when his rights were restored, but answered “yes” to Question 28.

Hoshizaki then joined the Fair Play Committee, an organized resistance to the draft led by an older Nisei named Kiyoshi Okamoto and co-leaders such as Frank Emi. Emi stated that the participants “wanted to make sure no one mistook their opposition to the draft on constitutional grounds for allegiance to Japan.” Unfamiliar with this part of the camp story, Higuchi writes that in getting to know Hoshizaki, who serves on the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation Board, her respect for his “strength and moral character” as a resister solidified. Hoshizaki and members of the Fair Play Committee eventually went to prison for resisting the draft. Later, Takashi did join the Army and served in the Korean War and had a successful career as a botanist.

Asked in an interview about the roles of people like Mike Masaoka and Bill Hosokawa, the editor of the Sentinel, the Heart Mountain camp newspaper, which pushed military participation by the Nisei, Higuchi observed that “they were all victims” at that time. “You can’t pass judgment now.” In her book, Higuchi notes the role that Masaoka played in getting the redress legislation passed and how Hosokawa at age 84 grudgingly accepted that the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation should acknowledge the resisters.

Shirley remembered that she and Takashi Hoshizaki “butted heads” when she first joined the HMWF Board. In the beginning, she wasn’t sure why she agreed to take her mother’s place. But eventually, she acknowledged, “this became my dream.” In embracing the project and becoming Board Chair, she found that she won the respect of Hoshizaki, who said simply, “Shirley, you’re doing a great job.”

In trying to understand her mother’s mindset in raising her children, Higuchi looked at the psychological research done by people like Amy Iwasaki Mass, Satsuki Ina and Donna Nagata. According to Mass, “The insult, the pain, the trauma, and the stress of being imprisoned were so overwhelming, we used the psychological defense mechanism of repression, denial, and rationalization to keep from facing the truth.” Because most Nisei were unable to share their experiences with their children, it created what Higuchi termed the “Sansei effect, the condition in which my generation of Japanese Americans strives to achieve perfection while knowing it is not possible. We grew up with the expectation that we would remain quiet, humble, and presentable, but some of us crumbled under the pressure.”

In the interview, Shirley observed that there are “a lot of unresolved (psychological) illnesses. Our work has just begun. We need healing and a place to do it like with the pilgrimages. What I learned is if you’re healthy, you need to help others.”

Higuchi ends the book with a trip to Japan, where she meets her relatives and gains insight into her grandmother Chiye Higuchi. She is told that her grandmother’s niece Sumiko Aikawa had learned about the family’s hardships in America when Chiye had visited Japan. The emotional outpouring of her experience with Sumiko made Higuchi realize how much damage the war did to Japanese Americans.

“The Japanese American incarceration and the war itself had fractured our families and also our ability to connect with our heritage, which the Nisei, the quiet Americans, locked away with their memories of the incarceration,” Higuchi concluded. “While we strove to be the best Americans, we were taught to be ashamed of being Japanese, too. It has taken me a lifetime to realize that I am not alone; there are other Sansei daughters like me.”

The end result is that after all Shirley has gone through with the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation and uncovering her own history, she feels that “my mother is at peace now.” And as she writes in the book, “I am finally at home.”

* * * * *

Shirley Ann Higuchi will be joining actress Tamlyn Tomita in a Zoom conversation moderated by filmmaker and news anchor David Ono, hosted by the Japanese American National Museum on January 9, 2021 from 2:00pm to 3:30pm PST. Click here to learn more and to RSVP.

© 2020 Chris Komai