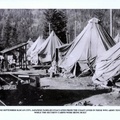

During the Second World War, George Doi and his parents and siblings were imprisoned in an internment camp at Bay Farm in Slocan. After they were released, Doi’s father started a logging business in the Slocan Valley. Later, he worked for many years in the B.C. Forest Service locally.

In the first three parts of this four-part series, Doi described his family’s uprooting from their Vancouver Island home, their temporary internment in Vancouver, their train ride to Slocan, and their life in the camp there. In this fourth and final installment he explains that the end of war did not mean the end of his family’s struggles.

* * * * *

With the end of war we should all have been excited that we could pack up and go home. Well, that is not what our government had planned for us. They gave us an ultimatum, to return to Japan (most of us had never been there) or go to Eastern Canada. That was in a remote part of our country, and many didn’t have a clue as to where it was in those days. So neither choice was an option.

So the past five years of agonizing wait to hear our fate had finally come — the order to get out and not return to the coast. It clearly showed the government’s insincerity right from the beginning and what they had planned to do with us, that they had no intention of letting us return. In good faith we had turned over our properties as ordered for safekeeping until our return but the Custodian of Enemy Properties sold everything so we would have less reason to return to the coast.

In the US, the incarcerated Japanese Americans got their freedom in 1945 – we got ours in 1949 — and in most cases their homes and businesses were not confiscated so they had something to go back to.

Racial intolerance was strong

Racial intolerance towards “the Orientals” was quite strong in those days, at times leading to protests and race riots. Some politicians, media, and influential people were inciting fears that their own jobs would be lost and the “Yellow Horde” would be taking over the country. The media stereotyped us as being sly and untrustworthy, and they hyped it up. There were a few politicians like Angus and Grace MacInnis who did speak up for us but most didn’t until much later.

I was still a young teenager but I do remember the whole camp seemed to be talking about having to move again and everybody was confused. Some said they had to go east and others said they had to go to Japan. Nobody knew and they were looking for answers, something in writing, but there were none. I think by this time the only authorized newspaper, New Canadian, which was published in Kaslo, had closed so there really weren’t any news sources that people could refer to.

Families were split up

In time the officials notified us that we had to move to eastern Canada, otherwise go to Japan. This government edict broke up many families, splitting children from parents who would never see each other again. There are many sad stories that need to be told and documented to do justice and to learn from it but many have passed now and gradually it will be buried history.

Government officials came to our house at least two times to tell us to move. The last time they came (as Mom told me years later) she met them at the door and when told we had to go, Mom was so infuriated that she told the officials in no uncertain terms (in Japanese and part English) that, “We are staying here! We don’t have any money and to go to Toronto would only mean to die there! We are going to stay and die here!”

I don’t know what went through the officials’ minds, but to be suddenly blasted by this small quiet-looking woman must have shocked them. They then told Mom that she would have to move out of the house because the camp would be closed by October (1946).

I noticed many families in Bay Farm had already moved. If memory serves me, I saw baggage piled in front of 3 or 4 houses on our street, waiting for a truck to haul them to the train station. Our immediate neighbours had all left; one forgot to close the door behind him. BCSC moved quickly and proceeded to sell the houses for I noticed one or two already towed away on our 1st Avenue. We were about the last one to get out that October.

Meanwhile there were similar commotions in other camps with people hurriedly packing to leave for the East or to Japan. I’m sure it was an emotional moment, as they parted with friends and families, forced again to move even further.

To a packed crowd in Slocan Buddhist Church in 1946, Nora Homma, a 15 year old, got up on the stage and sang the “Sayonara” song. Everyone was in tears including me and there was not a dry eye in sight.

Initially there were over 6,000 Japanese Canadians that signed up to be deported to Japan but when the order was later rescinded — after pressure from influential groups — many withdrew their names. About 4,000 had already left.

Expatriates were not welcome in Japan

From the stories I read of the expatriates, they weren’t welcomed in Japan. With the country devastated by nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki killing at the outset over 200,000 people and the carpet bombing earlier of Tokyo leveling half of the area and killing over 100,000 people (Kobe, Osaka, and other cities were also targeted), the country was in no position to accept an additional burden. People were starving.

In March 1945, over 300 US B-29 Bombers dropped 6,800 500-pound incendiary bombs over Tokyo. These bombs were filled with napalm gas, a sticky gel that clings to objects spreading a wide range and igniting fire. People were fleeing with their clothes on fire, jumping off bridges and into rivers that were already packed with floating bodies and screaming victims (cited here from victim’s testimonies).

Nagasaki was known as Christian city. When the plutonium bomb was dropped, it also killed many Chinese, Koreans, prisoners-of-war, priests, and missionaries.

‘Human beings are human beings’

Food was long gone and everything that was produced by people went to feeding the military and the prisoners of war. Our cousin in Japan repeated to me many times how hungry they were and how they searched the mountains for food. (Reading stories by expatriates and local testimonies they, too, all stressed hunger and extreme food shortages.)

We were walking home when a jeep full of boisterous American soldiers came speeding down and on to a collapsed bridge, crashing into the river. Our cousin quickly ran home to tell her father. He gathered coils of rope and dashed out the door. She yelled to her father, “But they are American soldiers!”

Her father replied, “Ningen wa ningen!” (Human beings are human beings).

Her father was presented with a sack full of vegetables and a citation for saving the soldiers lives. They came every week with vegetables so they were never hungry from that day. (This story was told to me by my cousin, a teenager at the time it happened.)

Freedom and independence at last

As for us in Canada we found a temporary shelter beside a high riverbank near the railway tracks. It was a log cabin abandoned many years ago and the rot had eaten away the logs and half of the roof and the floor under it had caved in. Even the rodents were long gone, but a few did return a week or so later. Fortunately the cabin was sheltered under a canopy of trees so when winter came, we had some protection.

But we didn’t have to stay in the cabin too long before we found a two-storey rental house on the other side of the Slocan River. It was roomy and on an acre of land with a few very old fruit trees that had long stopped producing fruits, except the Italian plum tree.

We had privacy and the most important thing, freedom and independence. What a great feeling!

On March 31, 1949, the federal government lifted the restrictions imposed on us under the War Measures Act, and we were given full rights of citizenship and the freedom to move anywhere in Canada.

In 1950 the Enemy Alien order was revoked and eventually about one quarter of those deported to Japan returned to Canada.

A secret history

For many decades after the war, this part of our Canadian history was never told and kept a secret. The oppressors felt no guilt yet chose to be silent, and the oppressed, living a strong cultural upbringing of shikataganai (can’t be helped) and gaman (persevere), tolerated it and they too kept silent and did not tell anyone. Their children and grandchildren were not aware of what their elders had gone through until 30 or 40 years later, often after their parents and grandparents had passed.

After much pressure from the younger generation of Japanese Canadians and others, on September 1988 the federal government finally acknowledged that injustice was committed against Japanese-Canadians during World War II. Together with an official apology the government paid $21,000 to each person affected.

Life after the War Measures Act was lifted

Our life had changed completely. We were able to think about our future and pursue our dreams like everybody else and live a normal life again. We worked hard to catch up and make money to buy the essentials around the house. We had no time to play or entertain.

We lived in this two-story rental house for about 12 years then around 1959 we bought the Pink House (had pink asbestos siding) in Slocan City.

Gradually our family of 12 started to disperse.

Mae and Edna ran our Mae’s Snack Bar in Nelson.

Rosie, Aggie and Mari, after graduating from high school, left for Vancouver to take up secretarial courses, Stan went to Selkirk College and the youngest, Gary, headed for UBC. James, Larry and I were busy in forestry related work.

Today the Doi children (and their spouses) are all retired. In our lifetime we learned the value of honesty and hard work. We learned to be humble, caring, sensitive to others’ needs and to never give up hope for a better life. From early on we were taught and lived by our motto that “Society doesn’t owe us; we owe society.” It was easy for us to follow because we all loved work and didn’t have time to think of entitlements, assistance, or benefits.

Conclusion

This concludes my story. I tried to be as accurate as possible through the eyes of a child but memories do fade so I am open to correction. As you will note, I expressed my feelings and thoughts into the narrative so as to give you some perspective on the atmosphere and emotion existing at the time.

I carry no malice or bitterness as times were much different in those days. Also, I should mention that because we were incarcerated in close quarters, I was able to get a better overall view on situations around me and witness events that I would not have had if I lived under other circumstances.

*This article was originally published by the Nelson Star on June 4, 2017.

© 2017 George Doi