By July of 1931 the melon season was winding down in Southern California’s Imperial Valley. With fewer runners from the local produce companies wiring eastern wholesale markets, the Western Union telegraph office in the farming town of Brawley would reduce its business hours as it did each year when the harvest came to an end. But in the middle of the month a flurry of incoming telegrams caused quite a stir. The wires came from unheard-of sources—astronomical observatories across the country and scientists around the world. Causing even more disbelief was to whom they were intended—a diminutive Issei1 farmer named Masani Nagata. The modest bachelor earned worldwide acclaim that summer by discovering a comet. On July 23, 1931, a headline on the front page of the Brawley News trumpeted:

AMATEUR ASTRONOMER OF BRAWLEY STARTLES WHOLE WORLD FINDING NEW COMET – GETS MANY WIRES

Nagata was born in 1886 in Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan, where his father was also a farmer and amateur astronomer. And it was his father whom he credited for nurturing his fascination with the stars, constellations, and planets from a young age.2

Masani (also known as Masaji)3 immigrated to the United States in 1907 at the age of twenty-one. In 1910 he settled in the Imperial Valley where he grew truck crops on a small scale in the areas around Brawley and Westmorland. At times he was employed as a ranch foreman by the Sears Bros. & Company, a Brawley-based grower-shipper, and later by the A. Arena & Company, Ltd. of Los Angeles. For both produce companies he oversaw the growing of vast acreages of lettuce and cantaloupes.

The state’s Alien Land Law of 1913 prohibited Japanese immigrants from owning farmland and limited leaseholds to three years, so Nagata constantly moved from field to field. The discriminatory law gave rise to a distinctive transient lifestyle in the Imperial Valley. Issei tenant farmers—bachelors and farm families alike—lived in small, rickety, wooden shacks. They were built to be lightweight because when the farmers moved to a new field, they took their houses with them. The moveable houses were not equipped with electricity or indoor plumbing. Russell W. Porter, an associate of optics and design at California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, visited Nagata and was taken aback when he found that “His thatched roof home was made of sticks and burlap bags.”4

While farming, Nagata continued his avocation and even encouraged several of his cronies to take an interest in astronomy. He convinced them that it was an ideal hobby because irrigation was a 24-hour task and they could gaze up at the stars while irrigating their crops at night. Astronomy was only a whimsical pastime for most of his friends, but Nagata studied the subject in earnest. What was described as his “library” consisted of a “rough table piled high with books and magazines, [containing] the works of both Japanese and American scientists.”5 One of those books was Hokkyokusei sonohoka [The North Star and other subjects] published in Tokyo in 1926. It may have given him the idea to build a miniature planetarium that he called, “A View from Your North Window.” He rigged the contraption with a light source that produced twinkling stars and it revolved to show the position of different constellations in relation to the North Star.

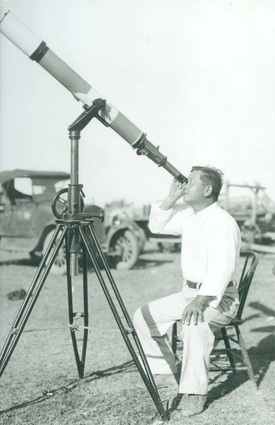

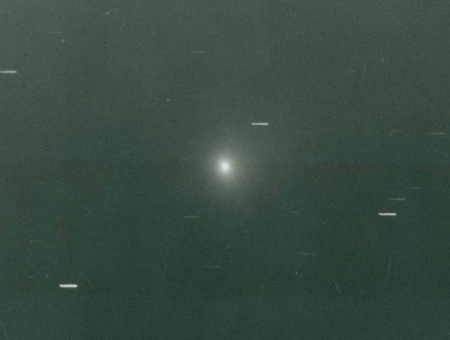

Just after dark on July 15, 1931, the Issei farmer was looking at the planet Neptune through his five-foot long refracting Zeiss telescope with a three-inch (80 mm) lens, mounted on a heavy, black tripod. At about 8:30 p.m. a nebulous star near the horizon caught his attention because he did not recognize it. Examining it again the next evening, he determined that it had moved approximately one degree to the northeast and suspected that it was a comet.6 Unable to identify it from his charts or astronomical journals, he telegraphed an apologetic inquiry to Mount Wilson Observatory in Pasadena professing his own oversight. It was no oversight. Dr. Seth B. Nicholson of the observatory confirmed that what Nagata found was a previously undetected comet. It was positioned in the constellation Leo, near the star Rho Lexis, about ten degrees to the right of Mars.7

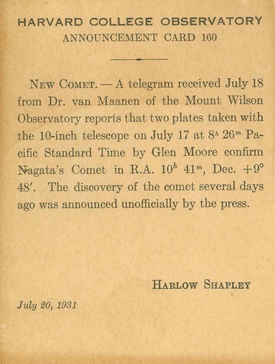

In the days that followed, requests for additional information and details about the comet were telegraphed to Nagata from the National Science Service, a scientific news agency in Washington, D.C. Harvard College Observatory officially announced the discovery of the new comet to the world. The name of the celestial object—Nagata’s Comet—was subsequently conferred by the International Astronomical Union. As was customary, it was named for its discoverer.

Nagata became an instant celebrity. He was hailed as a genius and he received letters and telegrams of congratulations from around the United States and Europe for being one of the first amateur astronomers to discover a comet. He was also inundated by local newspaper reporters and news correspondents from Los Angeles who wanted to learn more about the obscure Imperial Valley farmer who astonished the world by discovering, as the Brawley News reporter put it, “what astronomers with high powered appliances have missed for years.” When the same newsman asked Nagata to comment on the naming of the comet, he displayed his trademark modesty by replying that it should be named “for some worthier person.”8

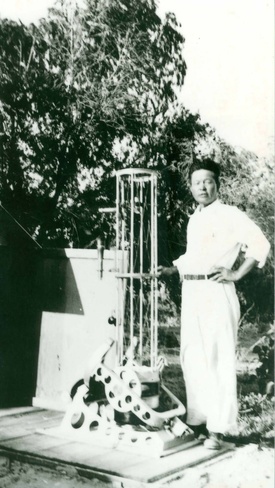

The unassuming Issei was bewildered by the “hullabaloo” made about him.9 Initially he even resisted posing for photographs but his polite protests did little to thwart his rise to prominence. An Associated Press photo of him sitting beside his Zeiss telescope and reports of his extraordinary achievement were picked up by big-city and small-town newspapers from coast to coast. On August 3, 1931, a camera crew from Fox Movietone News arrived in Brawley and filmed sound newsreel footage of the amateur astronomer. Being proficient in English, he made remarks in both English and Japanese for the talkie.10

In the wake of his discovery, a number of dignitaries from the scientific world, including the aforementioned Russell W. Porter, called on Nagata at his crude abode in the Imperial Valley desert, some six miles west of Brawley. Much to his consternation, a delegation representing the Astronomical Society of the Pacific showed up at his door on September 10, 1931. The delegation was led by Robert G. Aitken, the director of Lick Observatory near San Jose.11 Aitken bestowed upon Nagata the society’s Donohoe Comet Medal. Beginning in 1890, it was the 138th time that the prestigious bronze medallion was awarded to an individual for the discovery of an unexpected comet.12

Nagata joined the Citrus Belt Amateur Astronomers Club in Riverside, which was founded in 1933 by Dr. H. Page Bailey, a dentist and renowned amateur astronomer. Nagata was an active member and traveled to Riverside frequently to participate in the club’s functions.13

Nagata’s newfound fame made it possible for him to share his passion for astronomy with a wider audience. He arranged for Bailey to give lectures at the Brawley Junior College library. Such events were always free to the public. In 1936 the Issei farmer was invited by the Astronomical Society of Los Angeles to give a radio address, which he conducted in English and Japanese. In Brawley, he would set up his telescopes in the city’s parks so that local residents could gaze through them. On the night of August 7, 1937, he took several of his telescopes to Hawthorne Park and invited the public to view Fensler’s Comet. Earlier that evening the Brawley News announced that “residents of Brawley wishing to see the new Fensler Comet will have the opportunity tonight through the courtesy of Mr. Nagata, local astronomer.” The article continued, “The telescopes used by Mr. Nagata in his exploration of the stars are of his own construction.”

According to newspaper accounts, it was around 1923 when Nagata purchased his first telescope.14 Presumably, it was the Carl Zeiss refractor. Zeiss optical and scientific instruments were reputed to be among the best in the world, and he spared no expense despite his meager income. Commercial telescopes in general were typically too expensive for amateur astronomers, especially during the Depression years. Consequently, the making of telescopes was a widespread activity among amateur astronomy clubs. Nagata became skilled at grinding and polishing lenses and mirrors for his own telescopes. He learned much from Bailey and was grateful for his helpful suggestions and assistance.15 Nagata discovered that the Imperial Valley’s notorious summer heat had an adverse effect on the shaping of the mirrors, a problem he solved through trial and error.16 He reportedly built nine telescopes.17

As a result of the growing interest in astronomy, the Imperial Valley Astronomical Society was formed in March of 1938 with Nagata as one of its founding members. J. R. Hollingsworth was its first president. In recognition of his exemplary community service, Nagata was made an honorary member of the Brawley Rotary Club.

Nagata once quipped to his close friend and Ibaraki kinsman, Minekichi Kobayashi, of Westmorland, that he looked up at the stars because he suffered from headaches at night that prevented him from sleeping. When his headaches became unbearable late in the summer of 1938, he sought medical attention in Los Angeles. On September 8, 1938, he passed away at the Los Angeles County General Hospital after suffering what was likely a hemorrhagic stroke.

An urn bearing his ashes was returned to the Imperial Valley and a funeral service was held on the evening of September 15, 1938, at the Brawley Buddhist Church. The church hondo (main worship hall) was not large enough to accommodate the enormous crowd that gathered to pay its last respects. Many individuals were required to stand in the back of the hall and outside on the church’s veranda. Reverend Koyo Tamanaha officiated the service. Pallbearers were J. C. Archias, Yuzo Honda, Myron Howard, Minekichi Kobayashi, Ben Kodama, and Ralph Stilgenbaur. Brawley produce-shipper Tomosuke Uchizono delivered the eulogy. Remarks were also made by other community leaders in both English and Japanese. Those who spoke in Japanese included Reverend Susumu Kuwano of the Brawley Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church and officers of the Japanese Association of Imperial Valley. Among the English speakers were J. R. Hollingsworth of the astronomical society and G. K. Anderson representing the Rotary Club. In his tribute to Nagata, Anderson said:

Perhaps no other person in Imperial Valley has been so widely honored because of his way of life and his achievements in amateur astronomy. He placed service above self…The valley has lost a scholar and a gentleman.18

Epilogue

Nagata asked H. Page Bailey to build a telescope for him in 1932. The inventive designer and builder of telescopes did not disappoint his Issei friend. The telescope that he built was a truss-tube reflector supported by a novel equatorial split-ring horseshoe mount.19

To Bailey’s mind, Russell W. Porter and his supervisor John Anderson, of California Institute of Technology, had ulterior motives when they made the trek to the Imperial Valley between 1932 and 1933 to congratulate Nagata and extend an invitation to visit Caltech. At the time, Porter was designing the 200-inch Hale telescope, then the largest telescope in the world, for Palomar Observatory in San Diego County, and Anderson was the overall project manager. Bailey was convinced that they wanted to see the telescope that he had built for Nagata, or—more precisely—the telescope’s unique mounting.20 The concept was not entirely new, but Bailey became consumed with the idea that his design was appropriated by Porter for use in the Palomar project. When the Hale telescope was dedicated in 1949, it essentially resembled the one Bailey had built for Nagata but on a mammoth scale. Bailey never overcame his dejection after receiving no acknowledgment for contributing to the design of the Hale telescope.21

Nagata’s Comet was the first comet given a Japanese name.22 The Issei emigre did become known in Japan. A photograph of him with his Zeiss telescope appeared in the September 1931 issue of Tenkai [The heavens] published by the Oriental Astronomical Association.23 He also authored an article titled “Chikyū to suisei no shōtotsu” [Encounters between Earth and comets] published in the April 25, 1933, issue of the same journal.24 The Oriental Astronomical Association was founded in Kyoto, Japan, in 1920. In 1932 the association named Nagata as the representative of its North American branch.25

At the time of his death, Masani Nagata was in the process of constructing a large telescope to be mounted on the roof of the science building at Brawley Junior College. He was personally grinding the 12½-inch lens for the telescope.26 The project was never completed. The unfinished telescope sat neglected in the school’s storeroom for years until janitors eventually discarded it.

Nagata’s Comet has an elliptical orbit near 357 years.27 It will once again be visible from Earth about the year 2288.

Notes:

1. First generation immigrants from Japan.

2. Los Angeles Kashū Mainichi, “Nagata, Comet Discoverer, Prefers Lettuce to Fame,” June 26, 1932.

3. His personal name appeared as Masani on his passport but he preferred to spell it with a j, (Los Angeles Kashū Mainichi). In Japanese, with surname preceding given name, his name was written as 長田政二.

4. Berton Willard, Russell W. Porter (Freeport, Maine: The Bond Wheelwright Company Publishers, 1976), 237-238.

5. Lincoln Nebraska State Journal, “Japanese is Modest Over Finding Comet,” July 25, 1931.

6. H. M. Jeffers, “Nagata’s Comet,” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 43, no. 255 (October 1931): 356. The official date of the discovery of Nagata’s Comet is July 16, 1931.

7. Fitchburg (MA) Sentinel, “Lettuce Farmer Discovers the ‘Newest’ Comet,” August 18, 1931.

8. Brawley News, “Amateur Astronomer of Brawley Startles Whole World Finding New Comet – Gets Many Wires,” July 23, 1931.

9. Los Angeles Kashū Mainichi.

10. Brawley News, “Lick Observatory Honors Astronomer Here,” August 5, 1931.

11. Los Angeles Kashū Mainichi.

12. R. G. Aitken, “One Hundred and Thirty-eighth Award of the Donohoe Comet Medal,” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 43, no. 255 (October 1931): 349.

13. For activities in which Nagata participated, including photographs, see Bob Stephens, “History of the RAS: Part 1 – Roots . . . The Citrus Belt Astronomers,” Riverside Astronomical Society, www.rivastro.org/ras-history-roots.php.

14. Fitchburg (MA) Sentinel; and Harry Minami, “U.S. Japanese Wins Fame as Astronomer,” San Francisco Nichibei Shinbun, April 16, 1938.

15. Minami.

16. Willard, 237-238; and Anthony Cook, e-mail message to author, May 4, 2021.

17. Minami.

18. Brawley News, “Many Local Residents at Funeral for M. Nagata,” September 16, 1938.

19. For descriptions and photographs of the telescope and correspondence related to the Hale telescope issue, see Stephens.

20. Anthony Cook, e-mail message to author, April 12, 2021. Nagata’s telescope was one of three built by Bailey that Porter examined (Anthony Cook, e-mail message to author, July 2, 2021).

21. Anthony Cook, e-mail message to editor, Discover Nikkei, April 8, 2021.

22. Yamasaki Masamitsu, an astronomer in Japan, discovered a comet in 1928 but it was named Crommelin’s Comet.

23. Kyoto University Research Information Repository, “007_Related Academic Societies/The heavens/Vol. 11 Vo. 125,” Kyoto University.

24. Kyoto University Research Information Repository, “007_Related Academic Societies/The heavens/Vol. 13 Vo. 145,” Kyoto University.

25. Los Angeles Kashū Mainichi, “Astronomical Society of Japan Opens Branch,” June 4, 1932.

26. Minami.

27. Gary W. Kronk, Comets: A Descriptive Catalog (Hillside, New Jersey: Enslow Publishers, Inc., 1984), 125.

*I wish to thank Anthony Cook, former Astronomical Observer of Griffith Observatory, for informing me of the connection between Nagata and the Hale telescope, providing background information on H. Page Bailey and Russell W. Porter, sharing other material, and reviewing my draft with an astronomer’s eye.

**An earlier version of this article appeared in the Imperial Valley Pioneer (July 2001), the newsletter of the Imperial County Historical Society.

© 2021 Tim Asamen