Appropriately, as the National Basketball Association (NBA) celebrates its 75th anniversary, it included Wat Misaka as an important figure in its history. This might seem remarkable since Wataru “Wat” Misaka’s playing career consisted of only three games with the New York Knickerbockers. But Misaka’s mere presence on a roster in 1947 made him the first person of color to play in the Basketball Association of America (BAA), the predecessor to NBA, in the same calendar year that Jackie Robinson integrated Major League Baseball.

Historically, because America’s long and continuing struggle with issues of race has been most often viewed in terms of black and white, Misaka’s brief career was not recognized at the time as groundbreaking nor would it until 2000. That was when the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) premiered its exhibition, More Than a Game: Sport in the Japanese American Community which featured short video documentaries by JANM’s Watase Media Arts Center. Misaka was the topic of one of the videos, which included footage of him playing in historic Madison Square Garden when his University of Utah team won the 1947 New York Invitational (NIT) basketball championship. That appearance impressed Knicks’ general manager Ned Irish, who drafted and signed Misaka.

I was working at JANM when the exhibition opened and I was gratified when the NBA chose to correct its own history to acknowledge Misaka in response to the video. Before JANM’s exhibit, the NBA placed its year of integration as 1950 when Chuck Cooper (first to be drafted), Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton (first to sign), and Earl Lloyd (first to enter a game) were the pioneering Black players. The NBA rightfully still honor Cooper, Clifton, and Lloyd, but it now lists Misaka as the first player to integrate the league.

With his newly acknowledged status, Misaka, in his late 70s into his 80s, found himself as the central figure of numerous stories by such esteemed media outlets like Sports Illustrated and the New York Times as well as Utah newspapers and Asian American vernaculars. In 2008, he was the subject of the documentary, Transcending: The Wat Misaka Story. The Knicks honored him at Madison Square Garden and he got a second burst of publicity when Jeremy Lin and “Linsanity” exploded in New York in 2012.

It must have been bewildering to Misaka that a part of his life that lasted only a few weeks would turn him into a media sensation in his senior years. To a large degree, this late recognition overshadowed Misaka’s proudest achievements as an amateur basketball player and his status as a Japanese American sports hero when the Nikkei community was enduring its worse period of overt racism and discrimination. I believe Misaka handled it as best as anyone could.

I was fortunate to meet Wat twice. I first spoke to him when he came to visit Little Tokyo with his daughter Nancy in connection with the Budokan. Then in 2019, when he was honored at the Japanese American Citizens League’s national convention in Salt Lake City, filmmaker Cory Shiozaki and I traveled there to do video interviews with Wat. We were working on a potential documentary about Japanese American basketball. Cory arranged interviews with Wat, who was 95, through former JACL President Floyd Mori, one of Wat’s long-time friends.

There were obviously many questions that I wanted to ask, but personally, I was looking for a way to assess Misaka’s basketball abilities and his relationship with his Nikkei community in Utah. Unfortunately, near the end of 2019, Misaka passed away, so it was impossible to do any direct follow up. But I gained access to an unexpected source of information recently when someone gifted me a Japanese book by sports journalist Mikio Gomi, Nikkei nisei no NBA (The first Nisei Player in the NBA), published in 2007 and translated into English by Ralph Shriock in 2018.

In our interviews, my sense of Misaka was that he would rather talk about his University of Utah Utes’ basketball teams, his teammates and their successes. And with good reason. Misaka played on two different Utes’ teams separated by his military service: the 1944 squad that won the NCAA basketball title and the 1947 NIT champions. In the entire history of the University of Utah, no other basketball team has won either of those titles. The university just retired Misaka’s jersey, No. 20, this basketball season.

Before Wat was honored by JACL, he met up with his Ute teammate Arnie Ferrin, who was named All American in 1945. At six feet, two inches, he towered over his five-foot, seven-inch friend, but he lit up upon seeing Misaka. While both men were well into their nineties, they reverted to their young adult college personas, smiling and poking fun at each other.

Ferrin played for three seasons for the Minneapolis Lakers and won two BAA championships. When I offered that he had played with the legendary center George Mikan on those championship Laker teams, Ferrin corrected me and said, “Mikan played with me!” and laughed. His respect for Misaka’s basketball ability is also clear. “He was good enough to play (professionally),” he offered. “He ended up on the wrong team. They (the Knicks) already had two guards.”

This is where Gomi’s book helps to fill in gaps for me. Gomi outlines in some detail how Misaka’s professional career was cut short because the Knick coach Joe Lapchick didn’t have any use for Wat. After taking a pre-season publicity photo with Lapchick and teammate Lee Knorek, Misaka told Gomi, “Before that photo, and immediately after it, I never exchanged even a single word with Lapchick.”

“I think I played a total of 10 minutes over three games,” Misaka explained to Gomi. “I would go into the game for maybe three minutes. I was equipped to play as a pro. I wasn’t that aggressive, but I think I could have contributed to the team on defense.”

Misaka’s defense is the one of the things that had distinguished him during the NIT finals when the Utes played Kentucky, coached by the legendary Adolph Rupp. Wat is credited with holding Kentucky star Ralph Beard to only one point as the Utes beat the Wildcats, 49 to 45. Gomi interviewed Tatsuo Sumida, Misaka’s friend from the Military Intelligence Service (MIS), who Wat invited to New York for the tournament. Sumida recalled, “Beard was a really fast player, but Wat, who defended him, was even quicker. He really used his head to read the defense. Clever, smart. . . what other words can I use to describe how good Wat’s play was that night?”

Despite his defensive skills, the Knicks cut Misaka and made his professional basketball experience one that he wanted to forget. Gomi writes that when he asked Misaka about his memories of playing with the Knicks, Wat’s recollections are foggy and without much detail. Gomi interviewed Wat’s wife Katie and she recalled that when Misaka returned from New York, he didn’t talk about his experiences at all.

Gomi, who spent a section of his book comparing Misaka to Jackie Robinson (which Gomi recognized was never a fair comparison), did elicit this quote from Misaka: “If I just had the chance back then, even if it meant I would go through a lot of bitter days,” he stated, “I still would have wanted to follow the same path as Robinson. I really wished I could have stayed on the basketball court longer, even for just one more day.”

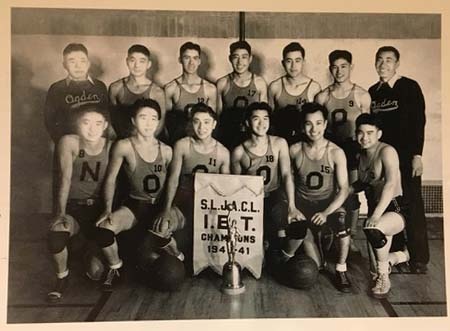

Misaka’s feeling of a missed opportunity likely stemmed from his almost unblemished record of his teams’ successes at all previous levels. He attended Ogden High School and his basketball team won the state championship in 1940 and a regional title in 1941. Wat then enrolled in Weber Junior College, where as a freshman he was named the Most Valuable Player as he led the Wildcats to the post-season championship. His next year, he led his team to the regular season title. Misaka was chosen the Weber Junior College athlete of the year since he also ran the 400 hurdles and finished third at the conference finals.

In the local Japanese American community basketball leagues, Misaka unsurprisingly made a big difference. The Salt Lake Nippons had won four straight championships when, in 1940, they took on the Ogden Nippons with Misaka and his good friend George Shimizu. Shimizu, the team’s star, was whistled for four fouls in the first half, but Misaka asserted himself with four field goals and three free throws and Ogden upset Salt Lake City, 30 to 23.

In assessing why Misaka proved to be such an outstanding basketball player, Shig Matsukawa, the administrator for the Utah Japanese American leagues, explained, “I think it was because he was such a smart basketball player. Certainly, he had speed, and as far as I know he was fastest of all the Nikkei Nisei (Gomi used this term instead of Japanese American) players in the country. But more than that, he was smart. And he was never a selfish player; he always knew how and where to move with the rest of the team. I’d say he was a lot like John Stockton of the Utah Jazz.”

When you follow a player’s career and his teams consistently win the title or contend, you don’t need to see his statistics to know he plays winning basketball. Intelligent players like Misaka instinctively know what their teams need to succeed and then have the ability to get their teams to execute the correct strategy.

In contrast, Misaka did not participate in the Japanese American leagues for the competition. “For me, it wasn’t all that important,” he told Gomi. “That (1940) was the only season I played Nikkei basketball and that was only during the tournament. I could play because it was held just after the school season had finished.”

What helped Wat to develop his sports skills was his friendship with George Shimizu, who was two years older. Like a big brother, Shimizu presented the biggest athletic challenge to Wat growing up. “He taught me a lot of sports, and I always played my best so I wouldn’t lose to him,” Misaka explained to Gomi. “But until I was 15, I could never beat him.”

Shimizu thought that Wat benefited from his mother Tatsuyo’s indulgence in that she allowed him to pursue school sports. According to Shimizu, most Japanese American families required their children to help with their family businesses and around the house after school. She made allowances for her oldest son and depended on her middle son Tatsumi to help at the barber shop in Ogden which she took over after her husband Fusaichi passed away when Wat was 15.

After returning from New York, Gomi reported, Misaka began coaching a Nikkei team called the Zephyrs in 1948. Even though the team won a title in 1950, Wat again downplayed its importance. “Yeah, sure, I was a coach for a while,” Misaka recalled. “But it wasn’t like we were regularly practicing much—maybe doing most of our practice just before the final tournament. And I don’t think I was that good of a coach. I was the type that liked to play more than I liked to teach. Around that time, I started getting more interested in things like bowling, golf or hunting.”

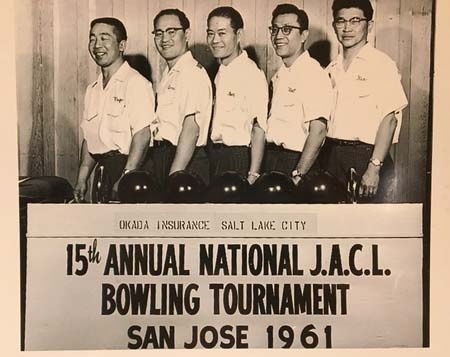

Indeed, Misaka became an avid bowler who served as the league director of the local Japanese American bowling league for almost 30 years. He annually participated in the Japanese American National Bowling Association’s tournament and it was clearly a way for Wat to connect with other Japanese Americans. Gomi, in trying to understand the function of Japanese American organized sports, observed: “Sports held among the Nikkei were less of a competition than a form of community interaction and friendship-building. That can be seen by looking at how the teams were formed, typically within the local community or sponsoring organization.”

Ultimately, Misaka felt his biggest individual accomplishments and his most valuable contribution to other Nikkei were the two University of Utah titles. “The most important thing for me was being the first Nikkei to win a championship in the National NCAA and NIT tournaments,” he explained to Gomi. “I was happiest to see that all of the Nikkei society was being recognized for what I did in a popular white sport like basketball.”

His family agreed. His mother’s cousin Kiyoko Hamada related, “I was so happy when I heard that Wat had won in New York. Even as a Japanese, he had done such an incredible thing in America. I think Wat was probably the most famous Nikkei Nisei in America at the time.” Wat’s brother Tatsumi added, “Wat was a hero to Nikkei all across the country. He was a source of pride for me as well.” Indeed, the local Japanese American community recognized Misaka in 1947 with their own award.

For me, that is quite an achievement and a reason to appreciate the true legacy of Wat Misaka.

© 2022 Chris Komai