This past May my senior prom was held at the Santa Anita Park race track. I dressed up, took pictures with my friends and felt like royalty for a day. After prom, I found out that the Santa Anita race track used to be a Japanese/Japanese American internment camp that my family was in.

At first I didn’t take it very seriously. All I knew about the internment camps was what I learned from my history class: During World War II, Japanese Americans were sent to camps and lived there until the war ended.

I didn’t learn about the terrible conditions and demoralizing nature of the camps until a few days ago, when I sat down with my aunt and she told me about my family’s experience.

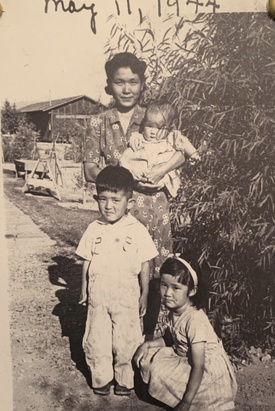

In 1942, both sides of my mom’s family were forced into internment camps under Executive Order 9066. My grandpa was only 5 years old.

His family owned a flower farm in Torrance, and they had lived comfortably. When the war started, they lost almost everything. They were taken to Santa Anita Assembly Center — the location of my future prom — and processed and stored like cattle until they got assigned to a permanent internment camp in Arkansas.

While they lived at Santa Anita, they and more than 18,000 other Japanese Americans were forced to sleep in horse stalls that had been lazily hosed down and still reeked of horse waste. The smell was so foul that barely anyone congregated inside, opting to gather in hot, cramped crowds outside while they watched the days pass by.

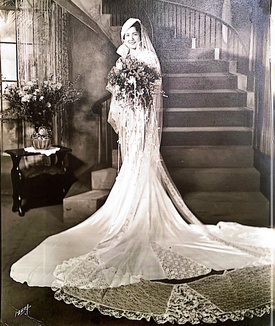

My grandma wasn’t even born yet. Her family had owned a profitable hotel in East LA, but after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, they were faced with indifference and discrimination from tenants.

Eventually, they were forced to sell the hotel for almost nothing. After Executive Order 9066, they were taken straight to Poston camp in Arizona, where my grandma would be born in 1943. When they had to pack up as much as they could carry and leave, my great grandmother had no idea what was going to happen to them. Although her space was limited, she made sure to pack encyclopedias with her clothes and essential belongings in case there was no school for her children.

After they were released, everything was different.

My grandpa’s name had been Koichi Nagami up until the war ended, but when he started school, his mother told him that his name was George, not Koichi. They no longer had a nice house on a farm they owned; instead, they lived in a barn that was constantly being eaten by termites.

My grandma’s family had a little more luck. A kind family had lived in their house while they were incarcerated and taken care of it, returning it to them as soon as they came back. Still, things weren’t perfect. My great aunt — who had been bilingual before the internment camps started — lost her Japanese by the time the war was over and could only speak English, meaning she could no longer communicate with her father in his fluent language.

It happened to my family. My grandparents weren’t born in Japan. They were born and raised in the United States, yet they were called traitors and forced to spend part of their childhoods in prison camps where they were treated like animals.

The experiences that my family faced aren’t unique. Across the nation, families shed their Japanese names and tongues. We were made to feel ashamed of who we are.

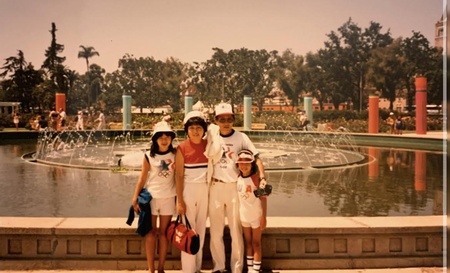

A part of me always wondered why my mom would take my brother and me to the nearest Japanese market at least once a month, even though it was half an hour away. Why even though she always talked about how she despised LA traffic, she would always arrange a day for us to go to Little Tokyo every summer. Why she was so excited when I told her I joined the Japanese culture club at my school, or made a friend who was Japanese.

Now, I realize why she made such a big effort to do all those little things. She was teaching me to love being Japanese — even after the whole nation had told our family to hate ourselves for it.

Generations later, we’re reclaiming our culture, one day at a time. We might not learn Japanese at home like we would prior to being incarcerated, but we do enroll in Japanese courses at our schools. We visit Japan and remind ourselves what we lost, but also what we have to regain.

As for me, a proud fifth-generation Japanese American, I’m making the effort to relearn who I am, so that I can keep loving what it means to be Japanese every single day.

*This article was originally published in The Daily Californian on November 6, 2023.

© 2023 Alicia Tsuyako Tan