Brian Niiya delves into the hidden history of a group of Alaska Natives caught up in the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans in our first “Ask a Historian” entry of 2023 at Densho's Catalyst.

* * * * *

Janice Sadahiro writes, “I just saw your YouTube video ‘Befriending a Native Alaskan boy in camp.’ I’ve never heard that Alaskan Natives were also sent to camps. Why? What other information do you have about this?”

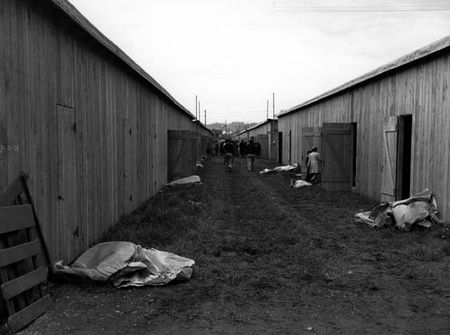

There were two different groups of Alaska Natives who were held in camps during World War II. The first was a group of about 900 from the Aleutian Islands. A chain of islands that stretches some 900 miles in southwestern Alaska, the Native population was evacuated after Japan bombed one island and invaded two others. Held in dilapidated camps with inadequate housing and medical care, some 10% of the evacuees died, and their villages were ransacked by American military personnel.

The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC)—the same body that studied the mass removal of Japanese Americans—concluded that while the removal of Aleutian Island Natives “was a reasonable precaution taken to ensure their safety,” there was “a large failure of administration and planning” in carrying it out. Based on recommendations by the CWRIC, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 approved $12,000 payments to each survivor and a $6.4 million trust fund that would help to rebuild churches and other structures destroyed by the US military and the clearing of wartime debris.1

This population had no interaction with incarcerated Japanese Americans, so the question refers to the other group, those Alaska Natives who were rounded up as part of the mass removal of Japanese Americans in Alaska. All Japanese Americans in Alaska—about 240 of them—were forcibly removed and incarcerated much as Japanese Americans on the West Coast were. An initial roundup of Issei men—and even a couple of women—took place after the attack on Pearl Harbor, followed by a mass removal in April 1942, ordered by Simon B. Buckner, Jr., the head of the Alaska Defense Command, under the authority of Executive Order 9066. As was true of Issei rounded up elsewhere, the Alaska Issei were transferred to mainland internment camps, with most seemingly ending up in the Lordsburg, New Mexico, army run camp.2

The mass roundup in April impacted two distinct populations. Those from southern Alaska included many small business owners and their families and were not dissimilar demographically from Japanese Americans from West Coast towns and cities. But the group from northern areas included the families of Issei men who had married Alaska Native women and had mixed-race children. Many lived in traditional Alaskan villages and had had little contact with other Japanese Americans. Their plight was further complicated by the fact that many of the Issei husbands and fathers had been separately arrested and interned.3

(The video mentioned in Ms. Sadahiro’s question refers to this latter population. The friend described in that oral history clip was Spiridon Hunter, who was of full Alaska Native ancestry. He came with his sister Mary Hiratsuka and her family; she was married to Mark Hiratsuka, a Nisei, and the couple had two young children. They had lived in Ekuk, Alaska.)4

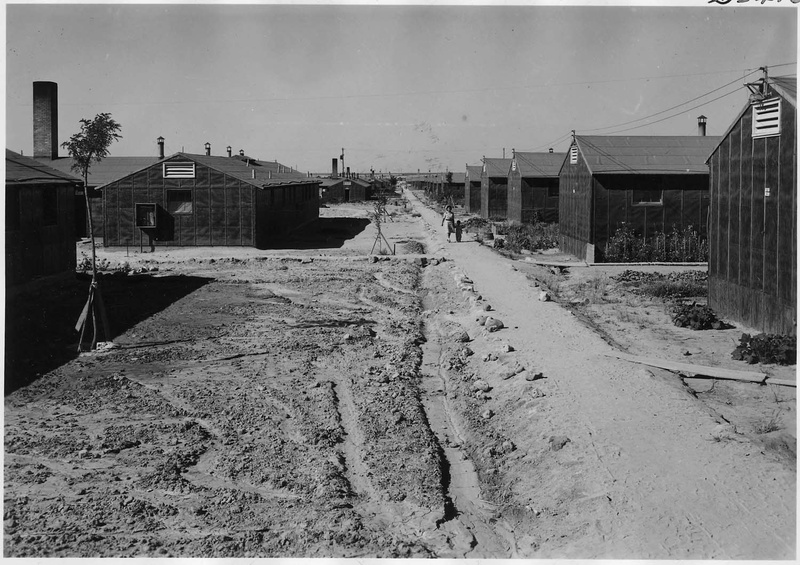

The remaining Japanese Alaskans were given little notice of their impending removal and were held first in local facilities including Fort Richardson, Fort Raymond, Ladd Field, Fort Ray, Juneau Air Field, and Annette Island Landing Field from April 20. From there, they were taken in two groups to the Puyallup Assembly Center, with 87 arriving there in the spring of 1942. They went with essentially the entire population of Puyallup to the Minidoka, Idaho, War Relocation Authority concentration camp in August and September of 1942. While most of the Alaska Issei seemingly remained in army or INS-run internment camps, some were later paroled to Puyallup or Minidoka where those with families could at least be reunited with them.5

A series of reports from Minidoka’s Reports Office paints a picture of the Alaska population. An undated report—but likely from the end of 1942 or early 1943—cites 135 from Alaska, of whom about forty-five were of mixed-race ancestry. Most of the latter were those with Issei fathers and Alaska Native mothers, though some also had Russian ancestry as well. There were also family members who had no Japanese ancestry. Given that many had no prior contact with Japanese Americans, “they form[ed] an isolated group in the center.”

A later report notes a number of individual cases: a nine-year-old boy of Japanese, Alaska Native, and Russian ancestry whose mother had died and whose father was at Lordsburg and who was being cared for by another Alaska family; two mixed race teenagers aged seventeen and fifteen who were there alone, their father at Lordsburg, and their mother still in Alaska; a mixed race 18 year old who had left his pregnant 17 year old Alaska Native wife back home, but had been trying to get his wife to join him after the death of their baby; a twenty-three year old mixed race woman with four children, whose husband was at Lordsburg; and other similarly heartbreaking cases.6

Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study researcher Charles Kikuchi interviewed a 28-year-old Alaskan of full Tlingit ancestry who somehow ended up at Puyallup because he had a Japanese surname due to his mother having remarried an Issei man. But because he lacked a birth certificate, he was rounded up and sent to Puyallup with his Aluet wife. He recalled that at Puyallup, “all the Japanese people gawked at us,” and that he hated the food, which was completely different from what they were used to. Though he managed to get out after just a few days by joining a sugar beet crew in Montana, he and his wife ended up in Chicago with a baby and another on the way, unable to return to Alaska.7

I’m not sure what becomes of the Alaska Native population in Minidoka. While later reports detail the difficulties Alaska business and property owners faced due to their sudden removal and the hostility of Alaska government officials, there is little on the fate of the Alaska Native group. The Minidoka Irrigator reported that Frank Yasuda was the first to return to Alaska, leaving in April 1945. A May 1945 report states that most of the Alaska inmates had already left the camp—aside from Yasuda and perhaps one other, to destinations other than Alaska—”and so do not constitute a big problem here.” Even after exclusion was lifted, those wishing to return to Alaska had to secure clearances from the commanding general in Alaska and the provost marshal general in Washington, DC until the fall of 1945. Those wishing to return also faced limited transportation options through 1945. The official WRA statistical volume reports that only 49 left for Alaska from Minidoka, a fraction of the number who had come from there.8

It is hard to imagine the unique hardships the Alaska Native group faced, not only being held in concentration camps thousands of miles from home, but being imprisoned with an entirely unfamiliar population, separated from family members, and with little clarity on their future. They represent another tragic story, collateral damage of the ill-conceived and racist mass removal and incarceration policy.

References

1. Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1982), 317–19; Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied Part 2: Recommendations (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, June 1983), 10–12; Native Voices Timeline, National Library of Medicine, accessed on Dec. 13, 2022.

2. Morgan R. Blanchard, “Level II Cultural Resources Survey of the Fort Richardson Internment Camp (FRIC), Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER), Alaska (Redacted),” (Anchorage, Alaska: Northern Land Use Research Alaska, LLC, 2016), 20–21, accessed on Dec. 13, 2022; Claus M. Naske, “The Relocation of Alaska’s Japanese Residents,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly 74.3 (1983), 127, 130.

3. Minidoka Information Division Press Release, Sept. 28, 1942, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records (JAERR), Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder P2.16; “Minidoka Reports No. 2: Alaskan Evacuees,” JAERR, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder P3.95:1.

4. Carl V. Sandoz to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, n.d., JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder P3.95:2; Minidoka Final Accountability Roster, Densho Digital Repository.

5. Louis Fiset, Camp Harmony: Seattle’s Japanese Americans and the Puyallup Assembly Center (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 85–87; “Minidoka Reports No. 2: Alaskan Evacuees.”

6. “Minidoka Reports No. 2: Alaskan Evacuees”; [Carl V. Sandoz], Minidoka Report No. 31, Jan. 25, 1943, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder P3.95:2; Carl V. Sandoz to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, n.d., JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder P3.95:2.

7. Paul Ozawa interview by Charles Kikuchi Apr. 10, 1944, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.967.

8. Frank S. Barrett, Report of the Legal Division [Minidoka], Nov. 1, 1945, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c; Minidoka Irrigator, Apr. 14, 1945, 1; Minutes of Staff Meeting [Minidoka], May 22, 1945, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder P1.15; Naske, “The Relocation of Alaska’s Japanese Residents,” 131–32; The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description (Washington, DC: United States Department of the Interior, 1946), 45.

*This article was originally published in the Densho's Catalyst on January 31, 2023.

©2023 Brian Niiya / Densho