A tragic episode in the transnational history of Nikkei in the Americas is that of the Japanese colonists who settled in the Dominican Republic in the 1950s and their return after 1961.1 The story of postwar Dominican colonization has been extensively recounted in different ways (and languages), by scholars such as Valentina Peguero, Toake Endoh, Alberto Despradel, and Chutaro Kobayashi, but it is useful to offer here some larger context, and then to speak of a rare positive aspect of these events: the mobilization by Japanese American communities to provide aid for the refugees.

The story starts with Rafael Trujillo, who came to power in Santo Domingo in 1930 and proceeded to establish a brutal dictatorship. From the beginning of his long tenure in power, Trujillo was interested in forging connections with Japan.

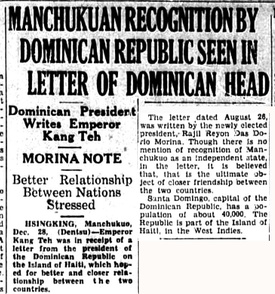

In the 1930s, after the Japanese invaded Manchuria and created the puppet state of Manchukuo, most of the Western powers refused to recognize the new status quo. The Dominican Republic was one of only a handful of nations to grant Manchukuo’s government de facto recognition.

It is not entirely clear why, but possible factors were admiration for the militaristic nature of Japan’s government; hope for greater trade with the Japanese, who bought Dominican sugar and cotton; or the presence of a common adversary in the form of the United States.

The closeness between Japan and the Dominican Republic went into eclipse during World War II. Trujillo declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, and trade between the two nations ceased. However, during the mid-1950s, in the aftermath of war and occupation, Japan once again sought foreign partners.

Since the 19th century the Japanese government, concerned by overcrowding in resources-poor Japan, had taken the lead in formulating policies to encourage resettlement of Japanese outside the home islands, whether by expansion or emigration. Now a new generation of Japanese politicians and Foreign Ministry officials sought once again to encourage overseas settlement. The citizens abroad would send home hard-currency remittances, while also growing the Little Japans around the world. Government officials were prepared to advance money to pay the passage of the emigrants, and opened training centers in Kobe and Yokohama to offer them instruction in foreign languages, culture, and farming techniques.

Government bureaucrats were ready to start small. According to Utah Nippo, in June 1956 Japan’s government announced its emigration goals for the 1956-57 fiscal year, with a target figure of 9,000 emigrants. They planned that half that number would go to Brazil (which had welcomed 7,717 migrants the previous year); 2000 to the newly-independent Southeast Asian nation of Cambodia; and the rest to the United States and Latin American countries. Six months later, Akira Yoshioka, head of the Emigration Bureau, announced that, for the fiscal year 1957-58, Japan hoped to use its aid to send about 14,180 of its citizens abroad, with an additional 30 percent emigrating on their own, without official assistance.

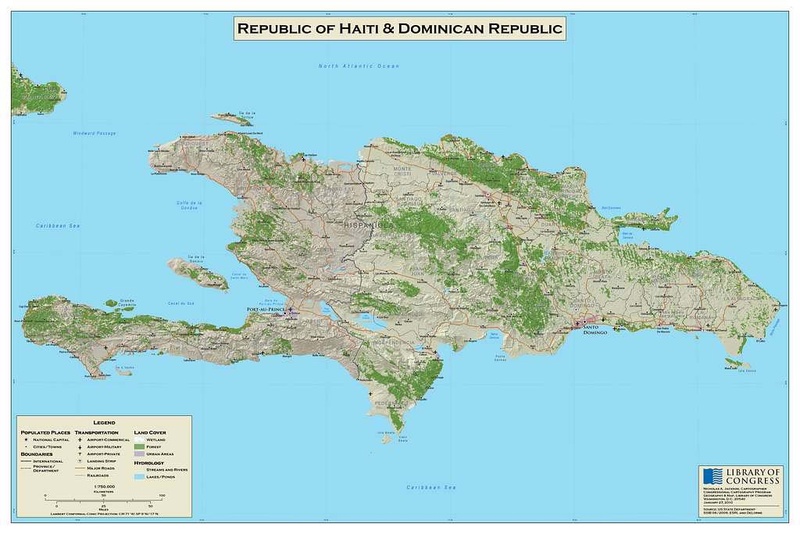

Still, if Brazil continued to be a favored destination for emigrants, independent and assisted, few other Latin American countries were interested in admitting new Japanese. Rafael Trujillo was willing to bring in small groups of Japanese farmers to the Dominican Republic, to develop its agriculture. Another incentive for him was the political situation in neighboring Haiti, where the status quo was overturned in 1957 by the coming to power of a populist demagogue, Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier, who promised reform but instituted a dictatorship. Trujillo seems to have been interested in installing a population near the border with Haiti as a bulwark in case of conflict.

In November 1954, Conservative Liberal Party legislator Tsukasa Kamitsuka, following a tour of Central and South America, told newsmen he had met with Trujillo, as a “semi-official' representative of Japan, and that Trujillo had expressed his readiness to accept up to 5,000 Japanese families as farmers in that nation. Soon after, the Japanese government made a preliminary agreement with Trujillo to organize emigration of Japanese farmers to the Dominican Republic. Tokyo would select the emigrants, provide them transport (for which the migrants would pay), and supervise the application of the program. The Dominicans would provide housing and land, plus a small wage.

In tribute to Trujillo’s great contribution to amicable relations with Japan, in March 1957 Emperor Hirohito presented the Dominican Generalissimo with the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum.

In March 1956, the Foreign Office reported that 35-45 Japanese farming families would be leaving that year as part of a pilot program. The initial target was 800 emigrants per year, but the program did not even achieve that modest goal: only about 1500 Japanese agreed to move between 1956 and 1959. This number was so tiny, compared to the thousands of emigrants leaving annually for Brazil during this period, that government officials may have concluded the results were not worth the resources they put into it.

More broadly, the idea of a global Japanese emigration program may have seemed too reminiscent of prewar Japanese imperialism. In the end, the Japanese government terminated the program in 1959.

The Japanese who did agree to migrate were resettled in eight colonies, six of them near the Haitian border, and two within the Cordillera Central. Apart from one group of fishermen, they were intended as agricultural colonists. The migrants were assigned to grow peanuts and rice, and later expanded to vegetable, coffee, and other crops.

There were problems from the start. The plots of land the migrants actually received were far smaller than what they had been promised, lacked water resources, and were plagued by poor roads and other transportation difficulties. The fishermen faced their own substantial difficulties. Hardly any of the immigrants spoke Spanish. They experienced culture shock in their new home, and were limited in their ability to interact with the surrounding population. Worst of all for the immigrants, their chief patron Trujillo was increasingly distracted and decrepit, as he faced international criticism and sanctions.

By the middle of 1961, many of the migrants to the Dominican Republic, dissatisfied by their conditions, had had enough. In May, the Japanese Foreign Office agreed to repatriate three fishing families who had settled there in 1956. In addition, 22 farmers and their families asked to be brought back from the area near the Haitian border where they settled, stating that the land they had been assigned was too poor for farming, and returned to Japan.

In September 1961, the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper reported that it had received letters from 19 families settled in the village of Neiba und neighboring areas, and that some 38 families, totaling 193 persons, were returning to Japan.The letter writers to the paper all complained that the land provided by the Dominican government was unfit for farming, and that they were barely surviving on small supplies of milk from the government. The newspaper article asserted, “Reports from the settlement also revealed that some of the housewives were engaged in prostitution in order to subsist.”

The movement became a flood after Trujillo’s assassination on May 30, 1961. As his tottering regime collapsed, Japanese colonists found themselves all but defenseless amid the chaos. Locals with resentments against the newcomers engaged in multiple forms of harassment. Such racial and political persecution, as well as poverty, motivated the Japanese to seek refuge in their home country.

By October 1961, the Japanese American press, following interviews with refugees, reported that of the 1490 Japanese who had gone to the Dominican Republic, almost half of them were thinking of returning home, unable to make ends meet because of the poor farming and fishing situation. “It takes money, at least about $100 to make preparations to return home, the refugees said. For the moment, there are about 190 now awaiting ships to return home.” The Japanese embassy announced that it would care for the refugees until they could sail, by offering $50 per month to each family.

Japanese officials initially reacted to the demands for repatriation by asking the government of Brazil to take the refugees, but when they received no response, the government agreed to undertake repatriation. In October 1961, the OSK cargoliner Argentine Maru took on 34 migrants from the Dominican Republic, who had been left destitute, plus another six from other countries. A further total of approximately 190 refugees returned to Japan on the SS Santos Maru in November 1961 and on the SS Africa Maru in January 1962, and 220 more followed on the America Maru in March 1962.

By May 1962, according to Oscar H. Horst and Katsuhiro Asagiri in The Odyssey of Japanese Colonists in the Dominican Republic, 672 of the Japanese who had moved to the Dominican Republic had been repatriated to Japan, and 377 relocated in South America (primarily Brazil, which finally agreed to take in a share of colonists). Only 276 remained in the Dominican Republic.

The fiasco of Dominican emigration gave rise to longlasting resentments. Recent books such as Toshihiko Kono and Yukiharu Takahashi’s Dominika imin wa kimindatta: Sengo nikkei imin no kiseki [The Dominican Immigrants were Abandoned: The trajectory of postwar Nikkei immigration] have presented the case that the Japanese government recklessly insisted on sending people to the most unfit corner of the Caribbean, for reasons that remain unclear, and that unscrupulous Japanese bureaucrats deceived poor farmers into emigrating with promises they did not keep.

Whatever the case, the migrants and their families engaged in an extended struggle for reparations. When the Africa Maru landed at Yokohama in January 1962, carrying 139 refugees, the 29 heads of the families insisted on remaining aboard ship until they could reach an accord with Foreign Ministry representatives. Their demands included payment of compensation for losses incurred from emigration to the Dominican Republic, and provision for homes and jobs in Japan. While they were ultimately persuaded to disembark, they demanded to stay together at the quarters of the Yokohama Immigration Station to conduct further negotiations with the Foreign Ministry.

These negotiations seem not to have led to a lasting accord. Rather, as Valentina Peguero reports, after filing a series of claims over the years, the refugee families ultimately brought a class-action suit in 1985 for compensation and pensions. In 2006, after futher interminable litigation, the Japanese Court of Justice issued a ruling. While the court acknowledged the government’s responsibility for the plight of the migrant families, it asserted that they had filed their case too late to be eligible to receive compensation.

Notes

1. Seth Jacobowitz assisted me with research for this article.

© 2023 Greg Robinson