The book Nikkei Legacy served as an important reminder to Canadians of the suffering that Japanese Canadians endured during the war.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the publication of Toyo Takata’s Nikkei Legacy, a book that put the history of Japanese Canadians into sharp focus.

For Japanese Canadians across Canada, Takata’s book captured the voice of the immigrant generation and served for decades as a “bible” of Japanese Canadian history, alongside Ken Adachi’s The Enemy that Never Was.

Nikkei Legacy served as an important reminder to Canadians of the suffering that Japanese Canadians endured during the war, and helped to lead the way to the federal government’s apology five years later.

Takata deserves special attention for his efforts to recover the lost history of Victoria’s Japanese Canadian community.

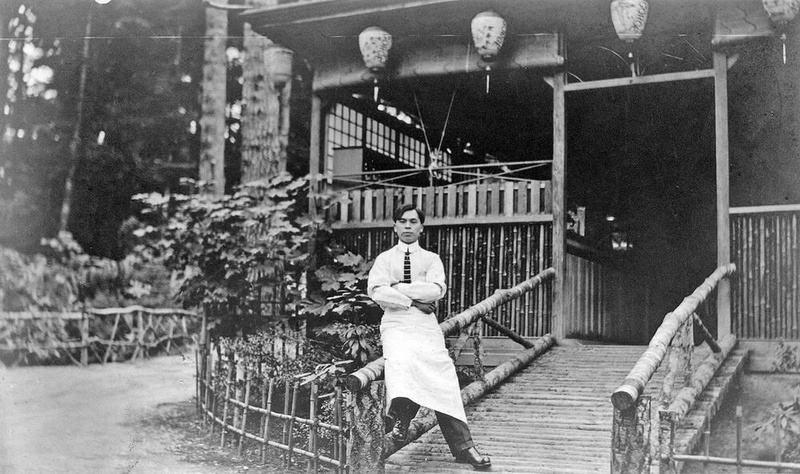

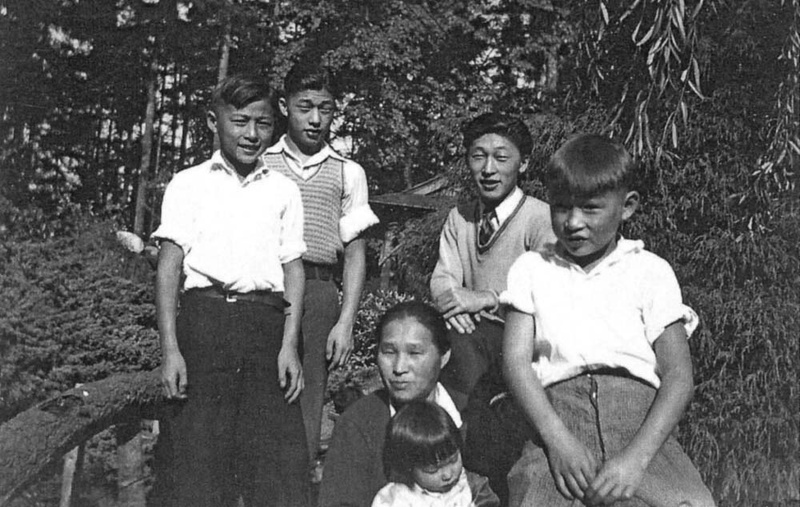

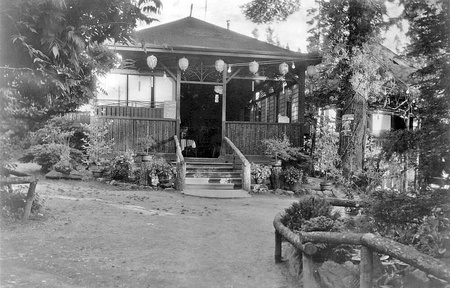

Victorians may recognize Takata’s name from his family’s Japanese gardens, which played a key role in growing the city’s popularity as a tourist destination and cultural hub for Vancouver Island during the early 1900s.

During the height of its success in the 1920s, the gardens entertained thousands of guests every year from around the world. The gardens were seized after the family was removed in 1942.

Following the publication of Nikkei Legacy and the apology, communities across Canada have begun to celebrate the history of the Japanese Canadians.

Thanks in part to the work of scholars and community activists, notably those attached to the University of Victoria’s Landscapes of Injustice Initiative, Victorians have made significant efforts to commemorate the city’s historic Japanese Canadian community and its impact upon the development of Greater Victoria.

Takata played a significant role in restoring his family’s gardens. As editor of the Japanese Canadian newspaper The New Canadian and president of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, he played an instrumental role in preserving several of Victoria’s cultural landmarks through his writings and his lobbying to restore the gardens in the 1990s.

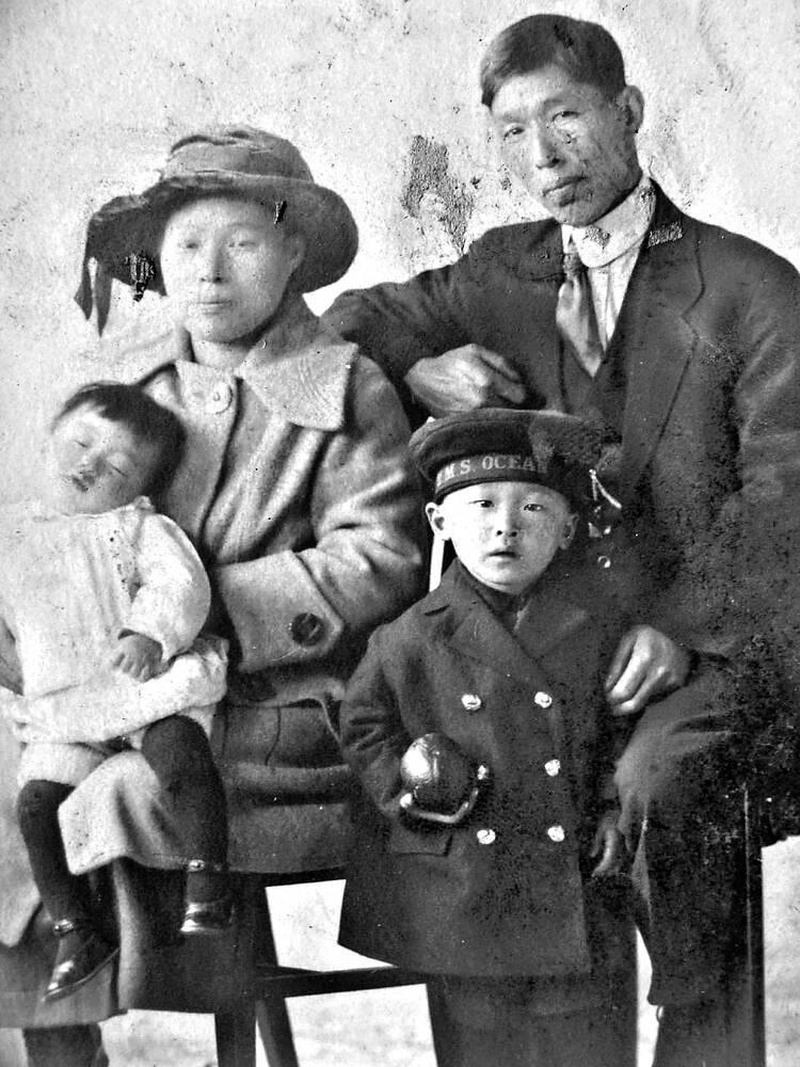

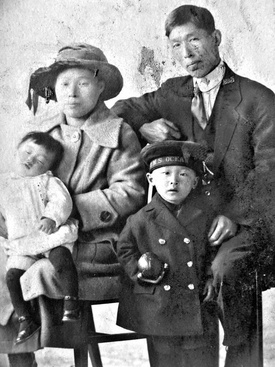

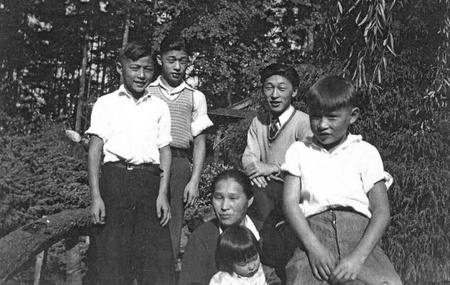

Born in Victoria in 1920, Toyoaki “Toyo” Takata was the oldest son of Kensuke and Misuyo Takata. As a young man, Toyo worked as a waiter and a clerk in the tearoom at his family’s gardens. He claimed throughout his life that they served better tea than The Empress hotel.

After graduating from Esquimalt High School in 1938, Takata worked various jobs, including at a logging camp in Coombs. He found it difficult to find jobs in Victoria due to racial discrimination.

In a 1984 interview with journalist James Adams, the former columnist for the Globe and Mail, Takata said: “Before the [Second World] War, places like the Macdonald and the Empress in Victoria liked to have Japanese bellhops and doormen. But the Japanese population at large never patronized those places. You couldn’t even get a job in an ice-cream parlour then.”

Shortly before Canada’s entry into the war, Takata enrolled in the Sprott-Shaw School of Commerce to learn typing and clerical duties, citing his desire to avoid serving as a combat soldier and having to kill others.

His expression of pacifist principle was made academic when all Nisei — people born in Canada whose parents were immigrants from Japan — were excluded from conscription.

In April 1942, the Canadian government removed Japanese Canadian families from the coast and sent them to inland confinement sites.

The Takata family had just a week’s notice to abandon their gardens and family heirlooms. They were taken on the Princess Joan to Vancouver, where they were confined at Hastings Park.

“The most traumatic experience for this band of refugees occurred a week later,” Takata told the Esquimalt Star.

“Forty of them, all males from 18 to 60, some married with families, were ordered banished to remote road camps in Interior B.C. and northern Ontario, under RCMP escort.

“One group composed of enemy aliens were sent to work on what is now the Hope-Princeton Highway. A handful were exiled to the Revelstoke-Sicamous section.

“[The] largest body of former Victorians, numbering about 25 and all Canadian-born, joined up with a contingent headed for an isolated, unmarked point north of Lake Superior called White River, with the reputation of being the coldest spot in Ontario.”

The Takatas were sent to the B.C. Interior, first to Sandon and later New Denver. In 1944, the Canadian government auctioned off the family’s property at bargain prices, deducting the auctioneer’s fee from the proceeds of the forced sale.

After the war, the family moved to Toronto, due in part to British Columbia’s exclusion policy that lasted until 1949, although Toyo tried to visit Victoria every year.

In 1948, he worked as an editor for The New Canadian, the largest Japanese Canadian newspaper in Canada. His column, The Weekly Habit, highlighted stories about the community and their struggles to readjust to post-war life.

He continued to write the column after he stepped down as editor in 1952, using it to preserve the history of Victoria’s Japanese Canadian community and to lobby the federal government.

In 1975, he wrote about the Osawa Hotel at 820 Fisgard St. He described the hotel as not just a favourite community dining spot, but as the entry point to Victoria for Japanese immigrants. “For hundreds, it was their first night in their new world,” he said.

Takata campaigned to memorialize Manzo Nagano as Canada’s first Japanese immigrant, and in 1977, he helped to organize the Japanese Canadian centennial, celebrating Nagano’s 1877 arrival in Victoria and the birth of Canada’s Japanese Canadian community.

In 1980, Takata successfully lobbied the Canadian government to organize a joint ceremony with the Japanese Navy at Victoria to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Japanese navy’s first visit to Canada.

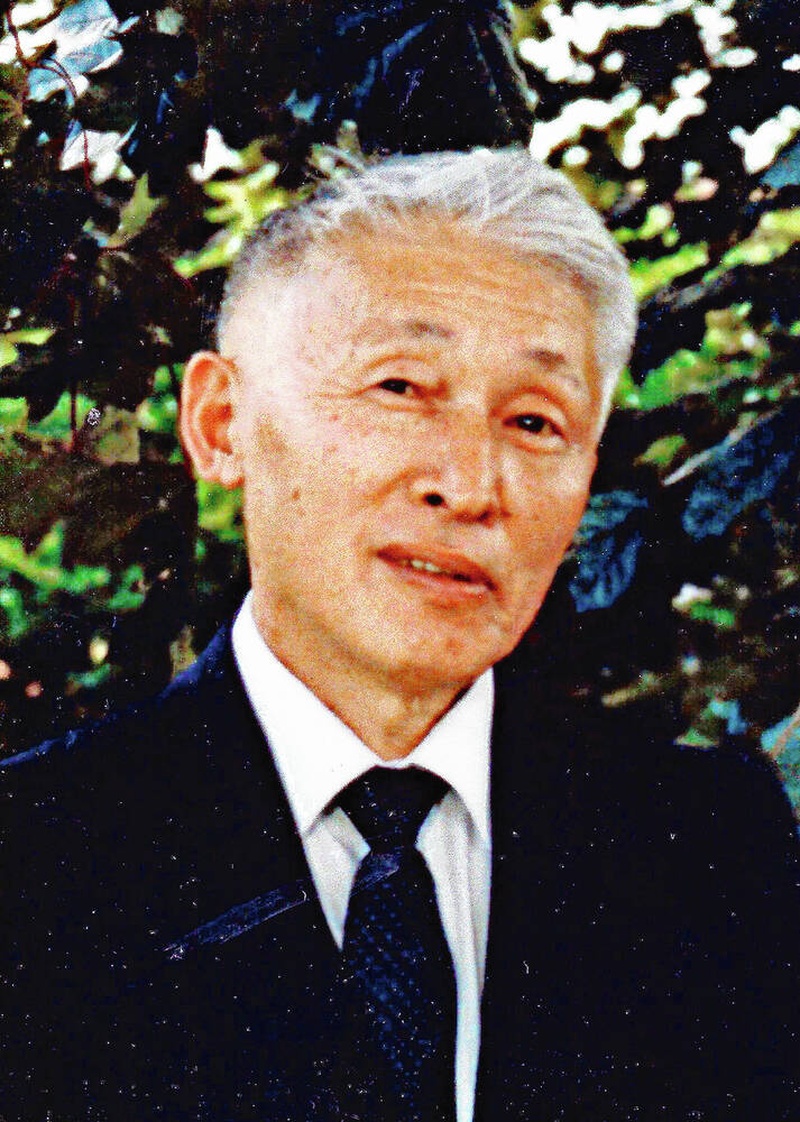

In 1983, after years of research and interviews, Takata published Nikkei Legacy, a highly readable history of the Japanese Canadian community from immigration through incarceration.

“It is almost like a Bible,” Frank Kamiya, of the Japanese-Canadian National Museum in Burnaby, said of Takata’s work.

Nikkei Legacy included several stories about the early history of Victoria’s Japanese Canadian community, including one about Sanjiro Nomura’s work as a lithographer for the Daily Colonist (a predecessor to the ;Times Colonist).

As awareness of Japanese Canadian history grew, some of the past wrongs were made right. In 1986, a silver tea set that had been taken from the family’s tearoom in the 1940s was returned to Takata.

In September 1988, then prime minister Brian Mulroney authorized a government apology and redress payments of $21,000 to each survivor of the forced removal and imprisonment of Japanese Canadians.

While Takata welcomed the apology, he said no amount of money “will ever compensate for what happened to us.”

In an interview with the Times Colonist, Takata expressed his bitterness over the experience: “It should never have happened.”

During the last years of his life, Takata devoted himself to the reconstruction of his family’s historic gardens at Kinsmen Gorge Park. He worked with local residents to restore the gardens to their former state.

In September 1995, Takata unveiled a Japanese bridge and granite marker at the Horticulture Centre of the Pacific in Saanich, which honoured his family’s contribution to Greater Victoria.

Takata died in Toronto on March 12, 2002, but his legacy lives on.

Two of the Japanese maple trees from the Takata gardens in Esquimalt were transplanted to the horticulture centre in 2008, becoming part of the Takata Japanese and Zen Garden.

Esquimalt unveiled a new Japanese tea garden in honour of the Takata family in 2009 and, in 2022, Esquimalt opened a cultural pavilion that recognized the contributions of the family.

Takata deserves recognition as one of Victoria’s important historical figures.

Whenever Victoria commemorates the contributions of Japanese Canadians, we carry on the legacy of Toyo Takata.

*This article was originally published in the Times Colonist on April 3, 2023.

© 2023 Jonathan van Harmelen