Traces of the war still remain

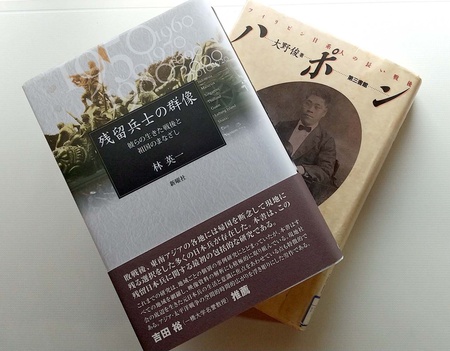

Last January, a book titled "Portraits of the Remaining Soldiers: Their Postwar Lives and the Gaze of Their Homeland" (by Eiichi Hayashi, Shinyosha) was published. Hayashi, whose previous works include "The Truth about the Remaining Japanese Soldiers" (Sakuhinsha), is a highly regarded scholar who has studied the social history of the remaining Japanese soldiers in Indonesia.

The term "remaining soldiers" refers to Japanese soldiers who, for one reason or another, did not return to Japan after the end of the Asia-Pacific War but instead remained temporarily or permanently in overseas battlefields. The author, who was born in 1984, mainly analyzes documentaries, films and other visual works that deal with remaining soldiers after the war, and analyzes how the former soldiers depicted in these works lived after the war, how Japanese and local society viewed them, and how they accepted the changes in their homeland.

When I think of remaining soldiers, I think of Shoichi Yokoi (1972), who was found hiding on Guam Island without knowing that the war had ended, and Hiroo Onoda (1974), who was found hiding on Lubang Island in the Philippines. However, through this book, I have only just learned, to my shame, that there were other soldiers who joined guerrilla movements after the war, escaped from internment camps, or stayed in the area for various reasons (or later returned to Japan). At the same time, I was made to think that Japanese people should know more about their compatriots who still bear the vestiges of the war.

Second generation Japanese left behind

In relation to this column, there is something to be thought about from the perspective of "Nikkei." This is because many of the remaining soldiers had children with local women. They are also second-generation Japanese, and they faced various problems such as social discrimination and identity.

For example, after the war ended, the soldiers returned to Japan, but their wives and children were left behind and had to survive the chaotic period after the war while bearing the negative aspects of being the second generation of war perpetrators. At the same time, they harbored feelings of longing for Japan, which was half their homeland, and for their fathers. There are many second generation Japanese, and even their descendants, who are suffering more than the Japanese soldiers who left.

This book introduces a number of video works that capture these Japanese people. One example is the Vietnamese in "To the Faraway Father's Country: The Journey of a Japanese Family Left Behind in Vietnam," which aired on NHK BS1 in April 2018. The book follows a Japanese-Vietnamese man who visited Japan in 2017 and visited the hometown of his father, a former Japanese soldier who had already passed away, and was given a watch that was a keepsake from his half-brother, and visited his father's grave.

Vietnam is one example, but the film introduces the real-life conditions of remaining soldiers in Asian countries and regions, including Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore, and encourages viewers to think about the postwar lives of Japanese families left behind.

Japanese in Asia

Generally speaking, when talking about "Japanese people" - people with some roots in Japan or the Japanese - people are referring to "Japanese Americans" or "Japanese Brazilians" whose descendants migrated to North and South America. However, the history of "Japanese people" in various parts of Asia, as well as in Vladivostok, Russia, which I introduced in a previous column, has rarely been covered in detail.

The reason for this is a fundamental lack of understanding of the modern history of Asian countries. In particular, the Asia-Pacific War has been interpreted from a Japanese perspective, with almost no understanding of the perspective of the Asian countries that were drawn into the war by Japan.

This is shown by the groundbreaking publication of "The Secret History of the Pacific War: Japan's War as Seen from the Perspective of Surrounding Countries and Colonies" (by Masahiro Yamazaki, Asahi Shinsho), published last year. This book examines the war that Japan started from the perspective of neighboring countries and regions, especially in Asia.

Davao's new Japanese town

In relation to the Asia-Pacific War, not only the families of soldiers who remained behind, but also many Japanese people who remained in the Philippines suffered hardships that are difficult to describe. I learned this from two books about Japanese people in the Philippines before and after the war: "Hapon: The Long Postwar Life of Philippine Nikkei" (by Ohno Shun, published by Daisan Shokan in 1991) and "Descendants of the Davao Country: Abandoned Philippine Nikkei" (by Amano Yoichi, published by Fumaisha in 1990).

Davao, the third largest city in the Philippines, located on the island of Mindanao in the southern Philippines, once had a maximum population of approximately 20,000 Japanese. According to "Happon," before the war, Filipinos called it "Davao Country."

Below, I will trace the relationship between Davao and the Japanese, mainly from Japón. In 1903 (Meiji 36), 23 migrant Japanese farmers began working in Asayama, and the following year, a mass migration of Japanese people began. Eventually, a Japanese community was formed, and the central figure was Ota Kyozaburo, known as the "father of Davao's development."

Ota ran a grocery store selling everyday items, and at the same time cultivated akaba, the raw material for Manila hemp, which he developed into a major industry. Japanese people settled in Davao to take care of the cultivation, and the city developed, with Japanese companies, a Japanese consulate, a hotel, a Japanese elementary school, a newspaper company, and more, creating a "Japanese town." Some of the Japanese who immigrated married local women and started families.

However, the situation changed dramatically with the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States. At the time, the Philippines was governed by a preparatory government for independence from the United States called the Commonwealth, but American and Filipino forces prepared for an invasion by the Japanese. In response, the Japanese army landed in the Philippines, initially overwhelmed the American and Filipino forces, occupied the Philippines, and began military rule.

Abandoned Children

The Philippines became a battlefield for the convenience of Japan and the United States, and its citizens were caught up in the conflict. Among these, Japanese people suffered hardships not only during the war but also after the war. Some second-generation Japanese were drafted as Japanese without a clear nationality. Some second-generation women married Filipinos, fearing retaliation from Filipinos because they were seen as Japanese. Some second-generation Japanese were killed by anti-Japanese guerrillas, and even after the war, some were executed by Filipinos as war criminals.

Many second-generation Japanese were left behind without knowing their identities because their Japanese fathers returned to Japan. There were also cases where they managed to find their fathers in Japan, only to be rejected. There were also Japanese-Americans who fought as Japanese, but were considered Filipinos because their family register was unclear, and they received no support from the Japanese government.

Many of the Japanese were fatherless and discriminated against for being of Japanese descent, and were economically poor. In many ways, the postwar period was tough for the Japanese in the Philippines who were involved in the war. Although private movements to support them were born, the Japanese government was slow to act, and it was not until 1988 that a survey team from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs began to investigate second-generation Japanese and Japanese nationals remaining in the Philippines.

And the problems facing second-generation Japanese continue to this day. "On December 20, 2022, a study session was held at the House of Representatives First Members' Building in Nagatacho, Tokyo, on the issue of stateless second-generation Japanese remaining in the Philippines," according to Kyodo News. Kyodo News reporter Takuro Iwahashi, who has followed the issue, introduces the voice of a person involved who appeals, "We were torn away from our families and were unable to obtain citizenship because Japan started the war. We hope the Japanese government will not abandon the second-generation Japanese who have survived in the Philippines."

© 2023 Ryusuke Kawai