I was once so naive and ignorant about Japanese Canadian history. For many years, I neglected to dig deeper to learn about my personal family history as well as the larger injustices inflicted on Japanese Canadians.

I was born in 1945 in Midway, British Columbia, just 9 miles west of Greenwood. In 1946, my family moved back to Greenwood, and that’s where I grew up. It was there that I was detained in a theoretical Canadian “internment camp” for Japanese Canadians until April 1, 1949.

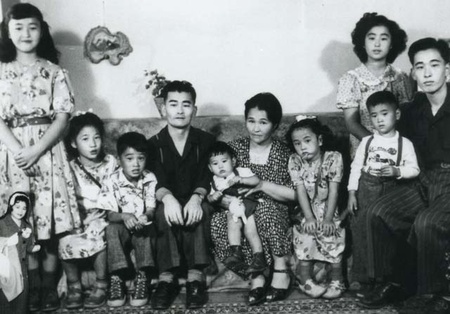

However, I didn’t even know that I was living in an internment camp, let alone that Greenwood was the first such camp in Canada.1 My parents never sat the children down to explain why they were sent to an internment camp. They were too busy raising their nine children, the two eldest—Kazuichi and Itsuko—of whom were stuck in Japan. They were not politically-minded. The local schools didn’t touch on the local history.

It’s only when I became an adult that I learned about my parents’ journey to the Greenwood internment camp.

Forced Relocation

My parents, Arizo and Hatsue (Maede) Tasaka, lived in Steveston before the war. Doomsday happened on December 7, 1941. The attack on Pearl Harbor and later the invasion of Hong Kong by the Japanese military turned the Japanese Canadians’ lives upside down. Canada declared war on Japan.

It was the perfect excuse for the British Columbia politicians to attempt ethnic cleansing of Canadians of Japanese ancestry. Under the War Measures Act, the Japanese nationals were declared “enemy aliens” to remove them “legally” first, but the government treated the Japanese Canadians as enemy aliens as well, so nearly everyone was to be forcibly relocated to parts unknown.

In March 1942, men 18–45 years of age were sent to the forced labour road camps around British Columbia, and to some extent to Ontario. However, some older bachelors decided to go to road camps since they would have a job and room and board. If they were sent to internment camps, the men felt they would sit idly by. Anyone who protested was sent to POW camps in Petawawa or Angler, Ontario.

In April, the forced relocation policy was set in motion. At this point, Greenwood Mayor W.E. McArthur, Sr. read in the newspaper that about 5,000 detainees were held up at Hastings Park with no takers. Most were from Vancouver Island, Fraser Valley, and up the northern coast. Mr. McArthur wanted to help with the war effort by accepting some of the Japanese Canadians.

That did not go well with the neighbouring communities. The mayor then asked the head of the B.C. Security Commission (BCSC) if he should erect barricades on the north and south sides of the highway, in case some may try to escape. The reply was, “No, don’t bother.”2

Journey to Greenwood

Father Benedict Quigley of the Franciscan Order read the want ad column by Mayor McArthur and quickly sprang into action. To cut to the chase, he and the mayor collaborated to bring mostly the Japanese Catholics from the Japanese Catholic Mission (JCM) in Steveston and from Vancouver near Powell Street’s Japantown.

Being Buddhists, my parents didn’t think they would be eligible to go to Greenwood. There were over 200 converts in Steveston. Fortunately, my mother’s cousin Buntaro Dominic Nakatsu was Catholic.

My mother asked Buntaro in her Steveston-Kishu dialect, “Sista ni nan-te (i)yutara en yo (What should I say to the Sister)?” Buntaro replied, “Ah, gi-mi chaunsu te (i)yutara eh yo (You should say, ‘give me a chance’).” Therefore, my mother went to see Sr. Eugenia of JCM and said, “Gi-mi chaunsu (Please give me a chance to go with the Catholics to Greenwood).”

With those words, my parents were sent to Greenwood!

Camp Arrival and Early Years

On April 26, 1942, the first set of Japanese Canadians arrived in Greenwood. Mayor McArthur had his welcoming committee and Sr. Jerome and Sr. Eugenia were at the train station to welcome their parishioners. Can you imagine that, a welcoming committee in 1942? Other communities, especially in the Okanagan, had “Keep Out” signs on the highway.

Mayor McArthur was expecting about 300 Japanese Canadians, but in total 1,200 were sent to Greenwood. As a result, housing at the camp was overcrowded.

My parents probably came on a later train. They were at first taken to the #1 Building or the old Pacific Hotel. There were 36 families, and more than 175 people filled the two floors of the hotel. There was one stove and one toilet per floor. The room was 10 ft. x 10 ft. to accommodate my mother and three young daughters. My father was sent to the road camp.

My brother Seiji was born on December 26, 1942. It was one of the coldest winters in that area, reaching -39 degrees F in February 1943. My mother told me that a kind gentleman friend scoured all over town to find scraps of coal and wood to keep the place warm so that a six-week-old baby would not freeze to death.

My father was released from the road camp since he was a barber, as it may have been considered essential service to cut hair for the Japanese Canadians in camp.

The #1 Building lacked privacy and was overcrowded. My father asked for a house. BCSC did give the family a two-storey house #141; however, they had to share with two other families that totaled 19 in all. Again, it lacked privacy.

After my sister Yayeko was born in March 1944, the Tasaka family found a place in Midway. Finally, in 1945, they had a house all to themselves. Unfortunately, my father had to take the bus or train to get to Greenwood to resume his barbering business.

This is where I was born in July 1945. Midway didn’t have a hospital, so a midwife delivered me. A year later, the family was back in Greenwood, so I had no recollection of Midway.

Growing Up in the Camp

In Greenwood, Sacred Heart School was established by the Franciscan Sisters of the Atonement in October 1942. Other camps weren’t as fortunate, as it took over nine months to set up the school infrastructure while the federal and provincial governments debated funding.

Attending Sacred Heart School, I looked like nearly all my classmates and spoke like them (pidgin English-Japanese). We would play day and night after school. Children didn’t even have a phone or a wristwatch, but “no mada,” they knew where everyone hung out, at the wood sheds behind the “apartments.”

Children played games according to the season. In the spring, it was marbles. The streets were not paved back then, so the damp, sandy ground made a perfect playing surface. Fishing along Boundary Creek was not only fun but provided food for the family.

Summer was building dams at the creek to raise the water level for swimming. Various games were played around the rows of wood sheds: Katana Kiri, Bang Bang, spitball fights, softball, Daily Shamble, and Peggi consumed the children’s lives to stay out of trouble. I once read in a book about Greenwood history that Greenwood had the lowest juvenile delinquency rates of all the internment camps.

Fall was mushroom picking, hunting, and Halloween. Winter was playing road hockey on packed snow by the post office, sleigh-riding down the mining roads, snowball fights, public skating, watching men’s hockey games, and participating in the ice carnival. Children looked forward to Christmas and New Year’s or Oshogatsu.

I had no reason to ask questions as to why I was living in Greenwood. What a great town, I thought. Thankfully, as I found out later, our kind Mayor McArthur was responsible for our well-being. Ensuring the well-being of Japanese Canadians was certainly not the intent of the federal government.

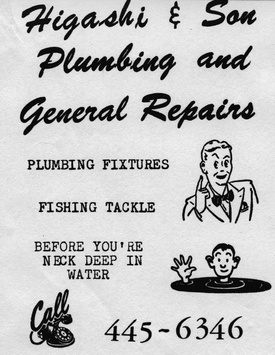

Greenwood “internment site” morphed into a community. Over 50% of the shops and businesses were owned or operated by Japanese Canadians even before 1949. As a result, Greenwood became an unofficial Japantown.

An “Empty Kettle”

I attended Sacred Heart School until it closed in 1954. Then, the students were transferred to Greenwood Elementary–High School. I struggled in school due to my difficulty with English comprehension. Nevertheless, I graduated in 1963.

All that time I was in Greenwood, I was only interested in sports, music, and dance. Japanese Canadian internment never really crossed my mind. I was like an “empty kettle” or, as the Japanese Hawaiian 100th/442nd RCT called the mainland Nisei, a “Katonk” or empty coconut.

During my career as a teacher and coach, I had very little time to put too much emphasis into studying our own Japanese Canadian history. It was always in the back of my mind, but no further.

However, one day my life changed, so to speak. There was a casual conversation and for some reason the internment camp topic came up. To say the least, the discussion got quite heated. Here I am, speechless because I had very little knowledge to participate in the debate. Some of my Caucasian friends spoke on my behalf. Being outnumbered, this older gentleman turned to me and quietly said, “Well, you guys started the war.”

That really bothered me! I knew one thing. Japanese Canadians didn’t start the war. I was so insecure at that point that I had no answer. I vowed to do more research and learn the reason why the internment happened.

To continue reading Chuck Tasaka’s journey, see “Part 2: Discovering Japanese Canadian History.”

Notes:

1. For additional details, see the article “Greenwood, B.C.: First Internment Center” on Discover Nikkei.

2. Watch “Explorations - Japanese Canadians” which includes Mayor W.E. McArthur, Sr. talking about his decision to accept Japanese Canadians to Greenwood.

© 2023 Chuck Tasaka