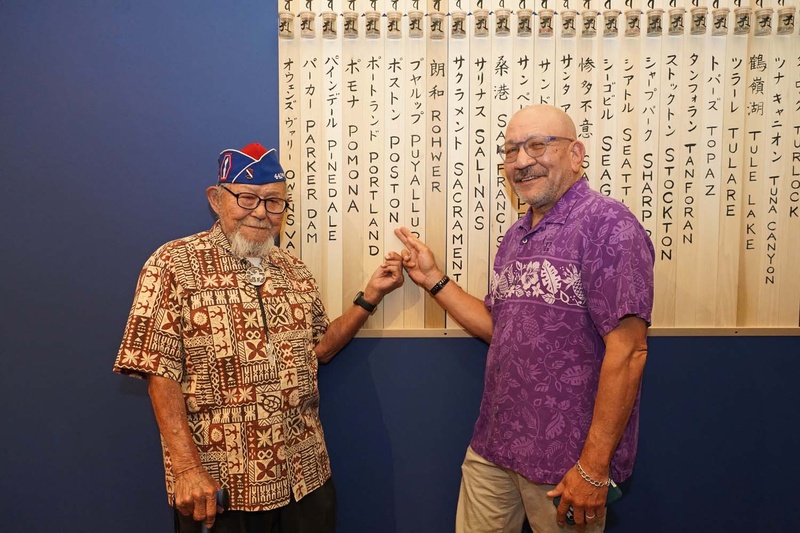

When Dennis Kunimura suggested to his father, 98-year-old former 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) artilleryman Hiroshi Kunimura, that they drive from their home in Ogden, Utah, to Los Angeles, to mark the names in Ireichō of family members held at both the Salinas Assembly Center and the Poston Concentration Camp, the elder Kunimura did not expect the overwhelming reception that awaited him.

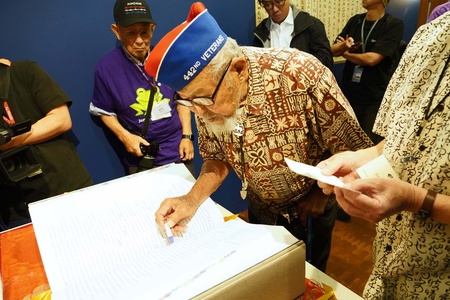

In fact, when the elderly soldier was welcomed by a three-man camera crew from Nippon TV, JANM executive director and CEO Ann Burroughs, Go for Broke president Mitch Maki, and a host of staff members, Kunimura scolded his son. “You didn’t tell me about this.”

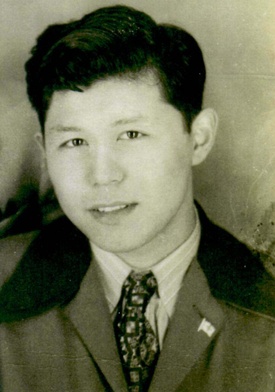

As one of only a few 442nd RCT veterans alive and active today, Kunimura insisted he didn’t deserve nor want any special attention. He was just another military man who served because he felt it was the least he could do for his country. It didn’t matter that he was risking his life for a government that held his family in concentration camps.

As he put it, “I’m an American and the enemy has attacked our country.” He even tried to enlist right after Pearl Harbor when he was only 16, but was turned down. When his draft status was changed a few years later after he left camp for a job in Chicago, he was a little annoyed and thought, “You guys didn’t want me then; why should I join now,” until he realized, “Hey, I’m still an American.”

He had no antagonism toward his country when he went overseas with the 442nd RCT in 1945 and was ordered late in the war to fight in some of its final battles in the treacherous Italian Apennines. Not as small of stature as most of his fellow Japanese American soldiers, Kunimura figured because of his size his superiors thought he could handle heavier loads. Subsequently, he got the grueling job of carrying loads of ammunition while climbing up and down steep mountain trails.

On one occasion under heavy fire, he recalls being ordered by his sergeant to climb 150 feet down the mountain to retrieve ammunition after their unit suddenly ran out. With German machine gunfire engulfing him, he thought to himself, “This is it for me.”

Never one to back down and always willing to “go for broke,” he recounted this death-defying experience with his usual good humor. “You wouldn't believe how fast I ran,” he laughed. Miraculously, he came back without a scratch.

Kunimura ended up living a full life with his wife of 70 years, Dorothy, who passed away only less than a year ago. Together, they had three children, Susan, Dennis, and Daniel. His wife and both sons also served in some capacity in the military.

It was Dennis and his wife Hollis, a 20-year veteran, who encouraged the family patriarch to join the more than 10,000 visitors who have thus far stamped Ireichō. They were joined by nephew Brian Ota, along with his wife Karen and their children, Eric and Elizabeth. Brian was the first person in the Kunimura family to mark Ireichō a few weeks earlier and who had also helped encourage his aging uncle to travel to Los Angeles.

Stamping Ireichō helped Kunimura to honor a family that had suffered much during the war years. Four of his sisters were stranded in Japan just before the war started, and only two of them were able to return to America directly after the war. Kunimura had to go to Japan following his release from the military for the sole purpose of helping rescue his two remaining sisters and bring them back to their hometown in Gilroy, CA. It took several years to finally bring them back to the US, and two of his four surviving sisters, Shigeko Nishiguchi (95) and Hiroko Kunimura (92) still live in Gilroy today.

Among those the elder veteran chose to honor with a hanko stamp were his mother Koiye Kunimura, his brother Masaru, his aunt Chise Tanaka, who died in camp, and his uncle Junichi Tanaka. When his own name was pointed out to him in the book of some 125,000 others who were imprisoned, he seemed modestly surprised and exclaimed, “That’s me.”

While driving from Ogden, Kunimura came up with yet another name he wanted to stamp. Kunimura told his son about a former Poston girlfriend, Sachiko Mary Ito, four years his senior, who held a special place in his heart.

While in camp, Mary’s mother would follow them around wherever they went. With nowhere to go for any privacy and with Mary’s mother lurking behind them, Kunimura never got very far with his older girlfriend. “Her mother never trusted me,” he recalls, adding with a smile, “She was right.” He never reconnected with Mary after he came back from the war, but he never forgot her.

Following his service in the famed 442nd, Kunimura became a lifelong military man. After WWII, he fought in the Korean War, and even went to Vietnam as a member of a logistical support team. He served as the Utah State Commander for the American Legion and has stayed actively involved in the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW).

Members of his immediate family who served in the military include wife Dorothy, who was in the Women’s Army Corp, son Dennis, who was in active service on ballistic missile submarines, and his youngest son, Daniel, who was in the Navy stationed in San Diego.

For the elder Kunimura, a life in service to one’s country came with a heavy emotional load. According to son Dennis, “I think my dad feels that in the back of his mind at any moment someone could come and knock on his door and take his civil rights away again.”

While at Ireichō, his father struggled to explain that fighting as part of the 442nd meant something far more important to their unit than to any other. He was there for a bigger purpose than fighting the enemy, but also to prove that Japanese Americans were fighting harder because they were doing it for their families still being held in camps.

These days, two years short of his 100th birthday, Kunimura stays active on his two-acre property in Ogden by fumigating his fruit trees, climbing atop his mobile lawn mower, and even making silver jewelry. At age 98, he can look back with pride at his life of service, but he doesn’t stop to think about it much nor want to talk about it. He seems happiest when not being the center of attention. However, it’s clear that he realizes that his American citizenship is precious and something he will never take for granted.

© 2023 Sharon Yamato