And what we see is our life moving like that

along the dark edges of everything,

headlights sweeping the blackness,

believing in a thousand fragile and unprovable things.

Looking out for sorrow,

slowing down for happiness. . .—Mary Oliver, “Coming Home”

It was like coming home when 17 sisters, cousins, grandchildren, and spouses, some who had traveled from different parts of the globe, met on the day after a large family reunion—this time to honor living and dead family members by placing hanko stamps on the names of those reverenced in Ireichō. With an immediate family of nine siblings and dozens more children, grandchildren, and spouses, our group was heavily weighted with four (out of eight) sisters who are my immediate family’s living camp survivors: Mary Jane Yasuko (93), Betty Emiko (91), Evelyn Akiko (88), and Phyllis Keiko (79), along with Jo Anne, the wife of my deceased (and only) brother Victor Katsuji.

As the youngest sibling whose work has been dedicated to writing and making films about the incarceration for the past 25 years, I convened this meeting knowing I was about to embark on a whirlwind ride to a dark happy/unhappy time that this family—with its positive outlook intent on moving forward—had somehow chosen to forget or ignore. Common to many Japanese American families, ours had managed to avoid facing the dark subject of camp by never talking about it. As my sister Keiko, who was born in camp, explains, “I don’t recall our parents nor my older sisters ever giving any significance—good or bad—to it.”

It’s difficult to imagine my sister knowing very little about the incarceration until only a few years ago, but she insists she never had “reason nor opportunity” to think about the circumstances of her birthplace. Besides, since she was only a year old when leaving Poston, how could she possibly remember?

When my oldest sister Peggy was 81, I interviewed her for an oral history for Densho, which included asking her about some of her memories being a teenager in camp. She told me she refused to dwell on bad things (which included being denied service at a local coffee shop shortly after the war) and had never said one word about camp, even to her friends also held at the Poston camp. She would admit, however, she never felt “as good as Caucasians,” but she wouldn’t concede it had anything to do with her being confined behind barbed wire simply because of her race.

As the eldest, Peggy was perhaps the sister whose life was most traumatized by camp, and I regret that with her death in 2019, I did not have the chance to speak more privately to her about it.

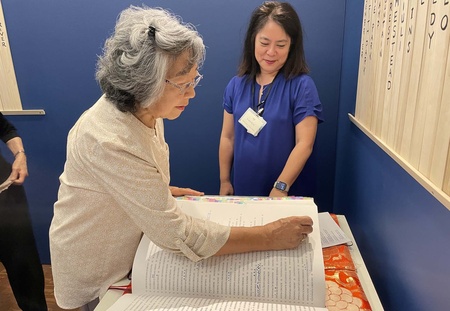

When we arrived to stamp Ireichō as we moved in and out of the museum’s air-conditioned rooms on a hot July day, I felt closer than ever to addressing this fragile subject with my other sisters as we finally came to mark the names of those once held in the stifling hot desert of the Poston concentration camp.

After being carefully instructed in the meaning behind Ireichō by expert facilitator Karen Kano, who talked about its Japanese Irei symbols, its complicated soil collection, and the solemn procession that brought it to the museum, I was grateful she could explain it to a family mostly uninformed as to its history.

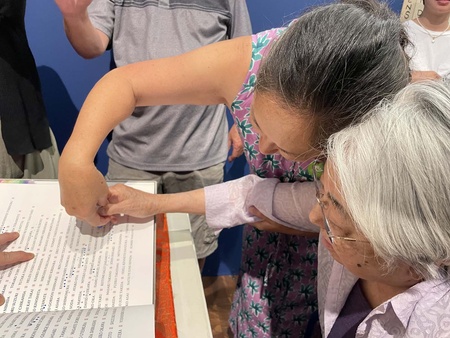

When my obachan’s name, Toyo Yamato, our oldest family member, was the first to be called, I jumped up to mark the name of the ancestor whose prayer beads I still have as a reminder of how lovingly she cared for us. I was followed by Keiko, who also didn’t hesitate to come forward to mark our beloved obachan’s name, even though she had hinted earlier to me she was reluctant to mark her own name, as if she somehow didn’t deserve it.

Others were slow to respond, seeming not to yet grasp the method behind Ireichō’s solemn purpose of reverently honoring our ancestors. However, as we all dutifully followed instructions on how to mark the book, I could feel the reluctance in the room soften and the weight of what we were doing become tangible. One of my sisters would later say, “I felt so important.”

Soon we were joking about the overflowing number of stamps each family name got by sheer number of all of us being there, laughing about the number of “likes” each ancestor received. Kano commented there was “palpable joy” in our family. As I saw it, we were always able to seamlessly use smiles and laughter to magically conceal sadness, sweeping the dark corners of the past under the soothing carpet of being together. As my eldest living sister Yasuko put it, “Being together with the Yamato sisters, I felt protected from the elements.”

Covering up our darker feelings may also have had some origin in my stern father’s insistence on not speaking out. Coming home from a long day at work to face at least five children at any given time, he demanded “no talking” at the dinner table. I knew him as capable of anger that could rock closed doors off their hinges, and we would do anything to keep the volcano from erupting. How much of his explosive anger was rooted in the dehumanizing camp experience will always be “unprovable,” but one can only imagine how many nisei men, stripped of their power, could survive unscathed.

Speaking out was replaced with two life-affirming substitutions: food and laughter. As one sister put it, “Even though we don't discuss subjects that are very deep, we enjoy the food, laughing, and eating Mom’s favorite chocolate peanut clusters.” It helps explain why the highlight of our family’s Ireichō experience at one point seemed to me to be less about honoring our past, but more about eating lunch together afterward at the nearby izakaya.

Despite the food and laughter, Ireichō stands out as a catalyst for families like ours to honor the past and move toward the future while not leaving behind things left unsaid. For the first time, I got to ask some family members about what they knew or remembered about camp, and as a result stepped inches closer to the truth that lay beneath the laughter. I also got to see and accept how others embrace the comfort and joy a large family offers.

I was also somewhat surprised by the response I received from a college-aged Gosei family member, Isabel Lee, when I asked her to write down how she felt about that day. In her quiet but studied way, she wrote, “Visiting this exhibit showed me the importance of not letting obstacles such as prejudice and segregation define your character and being strong enough to overcome whatever stands in your way.”

My sister Keiko, now learning more each day about camp, gathered her thoughts for me by carefully sounding out, “Gathering families to stamp Ireichō is acting on the understanding of a very ugly and suffering time in our history as Japanese Americans; and with each stamp honoring each name, each one, I feel that it changes the negative to a positive as this understanding will serve our children and the children of all Americans in the future.”

As for me, I suddenly felt myself turning to see the joy in the faces of family members who finally opened up to celebrate our own importance as bearers of our history. Out of the family darkness, I could feel our ancestors slowing down for happiness.

© 2023 Sharon Yamato