As part of my ongoing dissertation research on Congress and the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans, I have come across vignettes in several archives that illustrate the influential role played by members of Congress. While perhaps the most visible actions taken by Congress regarding Japanese Americans were holding public hearings (namely the Tolan, Dies, and Chandler Committees) and passing legislation (such as Public Law 503, the law that enforced Executive Order 9066), several individual members of Congress had a hand in the forced removal process.

Among the most fantastic cases of Congressional involvement (and duplicity) in the incarceration is the story of California Representative Alfred Elliott’s relationship with the Tulare Assembly Center. A representative from California’s Central Valley, Elliott ranked high among politicians who promoted the forced removal of Japanese Americans before February 19, 1942.

Following Roosevelt’s enactment of Executive Order 9066 and the Army’s decision to forcibly remove all Japanese Americans starting in March 1942, Representative Elliott agreed to lease his property at the Tulare Fairgrounds for the construction of one of the Army’s proposed assembly centers. In the months that followed, Representative Elliott turned the Army’s construction of the center into a political sideshow for his own personal benefit. He then played an instrumental role in forcing the Army to incarcerate all Japanese Americans living in the eastern sections of Kern and Tulare county - sites where thousands of Japanese Americans moved to in order to avoid incarceration in April 1942.

Born in Guinda, California on June 1, 1895, Alfred James Elliott grew up in Winters, California, before moving with his family to Tulare in 1910. In his younger years, Elliott worked as a farmer and livestock breeder. He eventually went into newspaper publishing, founding and editing the Tulare Daily News.

Even at a young age, Elliott showed an interest in politics. In 1918, Elliott joined the executive board of the Tulare Chamber of Commerce, where he remained a member for 19 years. He also became a director of the Tulare County Fair Association, a position which led him to locate his office within the Tulare Fairgrounds. He successfully ran for a seat on the Tulare County Board of Supervisors in 1933.

In March 1937, following the sudden death of Representative Henry E. Stubbs, Elliott announced his candidacy for California’s 10th Congressional District. Running as a Democrat on a platform supporting irrigation projects for Kern and Tulare Counties, Elliott received valuable endorsements from the papers of Tulare County (including his own), who dubbed him “the farmer’s friend.” He won the election by a landslide against Republican candidate Harry Hopkins (not the New Deal official Harry L. Hopkins).

Throughout his tenure as member of Congress, Elliott proposed legislation supporting irrigation for California’s Central Valley and resources for migrant farmworkers arriving in Kern and Tulare County. In particular, Elliott read a statement into the Congressional record in praise of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, whose portrait of the dismal conditions facing migrants in work camps had drawn outrage from conservatives. Elliott declared that the book accurately portrayed the subject.

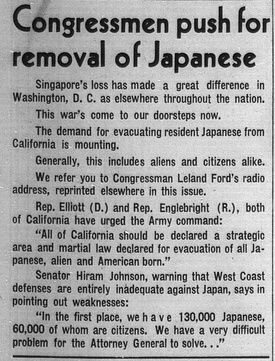

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Elliott joined the chorus of anti-Japanese sentiment among the West Coast Congressional Delegation. On February 18, 1942, the Rafu Shimpo ran a morose story headlined, “Congressmen Push for removal of Japanese.” The article cited statements made by Congressmen Leland Ford, Harry Englebright (House Minority Whip), and Elliott, who all insisted that “All of California should be declared a strategic area and martial law declared for evacuation of all Japanese, alien and American born.”

Elliott and the West Coast members of Congress got what they wished for; within weeks of February 19, 1942, the Army began initiating the removal of Japanese Americans from their districts.

The shelling of an oil derrick near Goleta, California by a Japanese submarine spurred Elliott to push the Army for swift action. On February 24, Elliott was greeted with applause before the House after shouting “we [should] start moving the Japanese in California into concentration camps and do it damn quick!” A few days later, Elliott wrote to General John Dewitt of the Western Defense Command urging him to remove all Japanese Americans from Tulare and Kern Counties. Elliott pointedly declared that several of his constituents, representing the American Legion, were demanding action as well.

To hold the Japanese Americans confined by official order, as the first stage in their forced removal, a new army agency, the Wartime Civil Control Administration was created. The WCCA undertook the creation of euphemistically titled “assembly centers,” and in March 1942, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began constructing barracks at several fairgrounds across the West Coast.

In cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco, the famous racetracks at Santa Anita and Tanforan were pressed into service. Elsewhere, fairgrounds in Pomona, Turlock, Fresno and other cities were taken over.

Among the sights selected for assembly centers was the Tulare County Fairgrounds. On March 26, 1942, the Army began construction on the site of the fairgrounds. Congressman Elliott, who managed and used the buildings as his local office, flew to Tulare two days later to confer with the Army.

Within weeks of the Army’s starting construction of the Assembly Center, several problems arose. On March 30, Colonel Karl Bendetsen, commanding officer of the WCCA, telephoned Congressman Elliott about the details involved in building the assembly center on the fairgrounds.

Elliott declared that he should get a thousand dollars for his crops destroyed by the Army for constructing facilities, and listed his concerns over putting the camp site near the business center of Tulare. He even went so far as proposing an additional fence surrounding the fairgrounds that would divide a portion of Highway 99 to separate a nearby hospital from the Assembly Center. After consulting with his staff the following day, Bendetsen agreed to put up the fence, recognizing it as a pure political gesture.

The Army had already begun to resent Elliott. In one dossier, an Army engineer described Elliott during their meeting on March 30 as “very assertive” and “anti-Army.” Some of this was attributed to the fact that his lip was swollen due to a bug bite, but the engineer also hinted to a slight sense of paranoia on the part of Elliott, who was obsessed with cutting wasteful spending with the project and expressed frustration over the fact that his fairgrounds were selected for the camp.

Elliott’s demands soon grew more numerous and outrageous. On April 3, Elliott telephoned Bendetsen urging him to immediately move out all 150 Japanese Americans from his district for fear that someone would dynamite the wells supporting the Tulare irrigation district. Bendetsen relayed his annoyance with Elliott to Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy, stating that Elliott never made a single constructive suggestion and simply stymied any progress on the assembly center.

At the same time, though, Elliott continued to push the Army to remove all Japanese Americans from California cities. On April 2, he made a press statement that “we cannot make good American citizens out of Japanese,” and that they should be put into camps for their own protection.

A few days later, on April 9, Bendetsen flew from Washington, D.C. to Tulare to meet with Elliott in person, and survey the areas surrounding the assembly center. On April 10, the military police captain in charge of Tulare assembly center took over the offices of the fairground building to set up his headquarters, not knowing it was Elliott’s personal office.

Outraged, Elliott demanded that the Army captain leave, and complained to Bendetsen, who phoned the Army Chief of Staff and General Dewitt. The Chief of Staff agreed to send Provost Marshall Allen Gullion to settle the matter.

Immediately after Bendetsen’s visit, Elliott sent a press release to the Associated Press criticizing Bendetsen’s handling of the Tulare Assembly Center. He accused the Army of wasting taxpayers’ dollars on the construction of the Assembly Center, arguing that the camp could have been constructed “from 45 to 65 percent less” and that construction damaged the fairgrounds for the upcoming fair (which had already been cancelled, along with other major gatherings that year). Elliott also accused one of the building contractors, R.H. Hougham of Hanford, profiteered off of the camp’s construction by taking in a ten percent profit – an accusation that Hougham vehemently denied.

The article enraged Bendetsen. In a call to John Abbott, a member of Congressman John Tolan’s staff who was involved in Tolan’s report on the forced removal of Japanese Americans, Bendetsen lamented that Elliott “is one of the people who screamed a lot about getting the Japanese under control.” Abbott responded that Elliott was “just probably one of the most unprincipled guys in the whole delegation,” described Elliott as a man “who’ll knife you anyway they can….”

The Army Corps of Engineers produced a rebuttal to Elliott’s outlandish claims. The report stated that the amount spent on building contractors was a mere fraction of what Elliott listed in his statement, and that the camp did not damage the fairgrounds. Unsatisfied, Elliott threatened the Army with a proposed investigation unless they moved the center to another location. The threats eventually blew over, and construction of the assembly center moved on.

A similar observation was made by political scientist Morton Grodzins during his interviews with members of the West Coast Congressional Delegation. In his field notes, Grodzins remarked that aside from pressing for money from the Army for his claims of damaged crops, Elliott used the Army and the “mishandling” of the Evacuation by Bendetsen as a means of boosting his image among voters. In a conversation between Congressman John Coffee and Morton Grodzins, Coffee stated that among the West Coast Congressional Delegation, Elliott ranked among the most racist of all.

© 2024 Jonathan van Harmelen