Ucluelet occupies a special place in Japanese Canadian history. Beginning in 1916-20, as Japanese Canadian fishermen were pushed out of the Fraser River salmon gillnet fishery, a large number came to the West Coast of Vancouver Island to look for new salmon trolling opportunities. The fishery was less competitive and racially charged compared to the Fraser River on the mainland. Trolling was first employed by the Nuu-chah-nulth people, using hooks and lines made of bone, yew, animal sinew, and kelp.

The Japanese and others, over time, innovated with stainless steel, aluminum rigging, hydraulic pullers, and artificial lures. Compared to the urban style of crowded gillnet fishery on the Fraser River, ocean trolling provided freedom to roam and pursue.

Ucluelet became the salmon trolling capital of the B.C. coast, rivalling Vancouver, Steveston, Campbell River, and Prince Rupert in the late 1960s for the chinook and coho salmon landed in a commercial fishing season.

Ucluelet, Tofino, and Bamfield are situated close to the fishing grounds, the shoals, and the banks of the continental shelf, with ideal harbours for everyday fishing in a season that stretched from April to October in the 1920s to 1960s. The main Japanese Canadian fleet travelled annually between Steveston and Ucluelet to catch seasonally migrating salmon.

Over time, a few men built beach shacks to live in and became seasonal or full-time residents of Ucluelet, which became the largest centre for Japanese Canadian fishermen on the West Coast of Vancouver Island since it was closest to the most productive fishing bank, La Perouse or “Big Bank,” located from 40 to 80 km south of Amphitrite lighthouse.

Fishermen of Japanese ancestry came to Ucluelet in such numbers that they created their own economy. By 1920-21, several hundred Japanese Canadian fishing boats used Ucluelet as their base harbour. Salt and ice were needed to preserve the Chinook, coho, chum, and halibut. Boat and engine repair needed organizing in-season, and then think of the rice, tea, and food products needed by the fishermen. The seeds of organizing the Ucluelet Fishermen’s Cooperative had been planted, but that is another story.

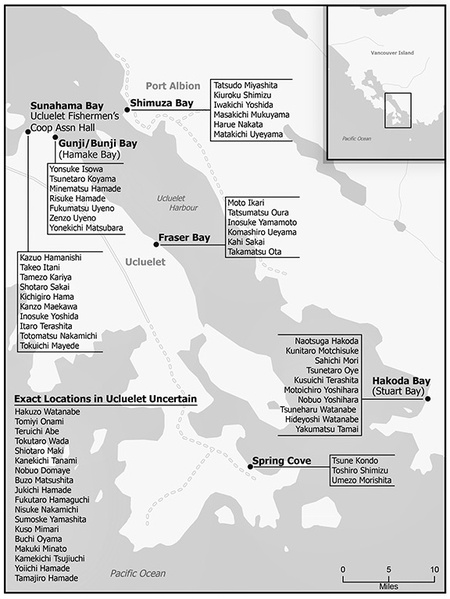

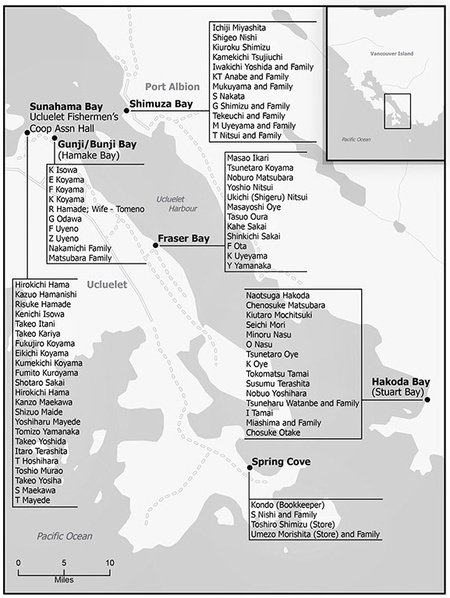

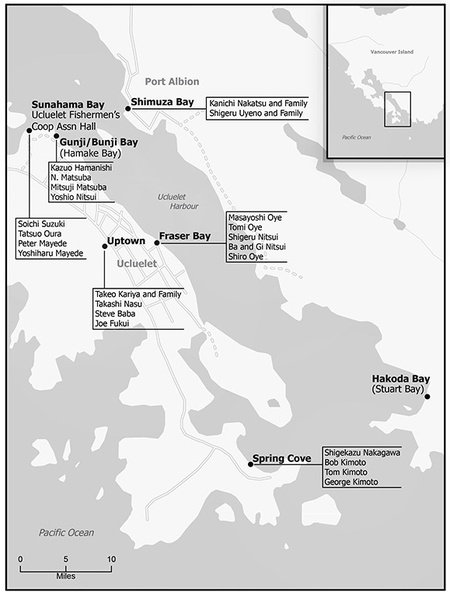

In 1922, the first of increasingly draconian and racially-motivated fishing licence restrictions were imposed against the Japanese Canadian fishermen, with a key feature being a residency requirement. This led many fishermen previously living in Steveston to bring their families and build houses in Ucluelet. Six distinct settlements were established in Ucluelet Harbour—Hakoda Bay, Shimizu Bay, Sunahama, Bungi (Gungi) Bay, Fraser Bay, and Spring Cove.

At their peak, each settlement was occupied by between 10 to 15 Japanese Canadian families. Others lived nearby but in isolated bays or places like Hyphocus Island. Land tenure was a mix of leasing, rental, ownership, and even pre-emption and some handshake arrangements.

Eventually, only 52 licences were issued to Japanese Canadian fishermen, so there is a story to be told of how licences were passed on from fathers to sons, extended family support systems, and even creative cheating with First Nation partners and others (since no other ethnic groups were restricted entry).

Rather than strong racial tensions, the First Nations, Japanese Canadian, and White Canadian settlements sometimes interacted but often maintained a respectful social and cultural distance due to linguistic and cultural differences. Mutual acknowledgment sometimes occurred via hand signals on the water, leaving gifts at the end of a float or children playing when chores or school was finished. The communities came together for emergency search and rescue or sports events. Overall, Ucluelet was a good home and safe harbour.

There were agitators who wanted all the Japanese Canadians removed from the fishery and the West Coast, and the Member of Parliament riding covering Ucluelet was one of the most anti-Asian politicians in Canadian history, AW Neill.

On Dec. 7, 1941, Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor lit the fuse for war with Japan and the total uprooting and dispossession of Japanese Canadians living in Ucluelet and elsewhere in coastal B.C. It all happened quickly, like a tsunami, and all men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry, regardless of citizenship, were swept away.

Although the Second World War ended in 1945, Japanese Canadians were not allowed to return to the coast until 1949, the same year they were also finally given the right to vote like other Canadian citizens.

If you or your family have Ucluelet roots, we would love to hear from you. We are preparing historical maps of Japanese Canadian residents in 1931, 1941, and 1961. Below are our drafts of the maps of the names of residents by sub-communities.

Any information you might have that could help enhance our understanding of Ucluelet’s Japanese Canadian community, whether before the Second World War or after, would be greatly appreciated. Please contact Paul Kariya at kariya@shaw.ca or Ian Baird at ibaird@wisc.edu.

*This article was originally published in The Nikkei Voice on January 17, 2024.

© 2024 Paul Kariya and Ian G. Baird.