In 1938, Aiji Tashiro was recruited as a faculty member at Appalachian State Teacher’s College (today Appalachian State University) in Boone, North Carolina. He was one of the first Nisei engaged as a regular faculty member by an American university. He was assigned to teach History of Western Civilization and creative writing.

In addition to his teaching duties, he was engaged as Landscape Architect. He would eventually design several buildings on campus, including what is now the Psychology building, plus a variety of faculty houses. Aiji's younger brother Arthur Tashiro came along with his brother and sister-in-law, and enrolled at Appalachian as a student.

In 1940 Aiji left the university and began a private landscape architecture practice in the nearby town of Lenoir. He drew up plans for a rock garden and pool to improve the public rose garden in the town of Hickory. In partnership with local county surveyor Jasper Moore, Aiji produced a topographical map of the site of a proposed airport, hoping to win federal funding for construction of the facility. He worked for a time as a reporter for the Hickory Daily Record newspaper,

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the coming of the Pacific War transformed Aiji Tashiro’s life. In the first days after the outbreak of war, he raced to reassure his neighbours that he was an American. In an interview with the Hickory Daily Record, he remarked that, while he was used to being taken for a foreigner, he had never visited Japan, and until he was ten years old had never even seen an “honest to gosh Jap.” When questioned about his feelings for Japan, he responded that he felt the same hostility towards Japan as all other Americans. He added that if his age and his being married had not prohibited it, he would have already enlisted in the United States armed forces, and that he still hoped to find some way to be accepted for military service.

While Aiji’s brother Arthur, still living in North Carolina, enlisted the day after the interview, Aiji—like his brothers Ken and Saburo—would struggle to enter the U.S. Army. When Aiji first enlisted in January 1942, he passed his initial medical examination and was accepted for service. However, once Aiji arrived at Fort Bragg for basic training, doctors quizzed him on his medical history and discovered his past case of tuberculosis. Since the doctors had no control over assignment of soldiers and they feared Aiji might be assigned to a branch of the service that would jeopardize his health, they informed him that they recommended discharge on medical grounds. (Ironically, his discharge was dated February 21, 1942, the week of Executive Order 9066).

Aiji was mortified and furious over his discharge, pointing out that he lacked any symptoms of tuberculosis. He undertook a prolonged campaign to reenlist. According to one newspaper account, he sent no less than 75 letters to bureaus of the armed forces, lawmakers in Washington, and friends around the country, begging to be accepted for service.

In an October 1942 letter to Philleo Nash of the Office of War Information, he outlined his efforts to re-enlist. (In the process, he gave a not-too-truthful account of his tuberculosis diagnosis: he claimed that in 1934 he had taken a chest x-ray on a whim to please his medical student brother Saburo, and that it had shown a “minimal lesion.”) Hoping to be accepted to the Army Specialist Corps, which had waived physical requirements, Aiji stated, he had applied to the Army’s Adjutant General, but was refused. Aiji obtained endorsements for entry into the Corps from his local representatives in Congress, H. L. Doughton and Carl Durham, as well as liberal California Congressman Jerry Voorhis. Despite all his efforts, he remained stuck in civilian life.

In his letter to Nash, Aiji remarked bitterly that his private architectural practice was gone due to the war, and that the “war tension” had caused him to separate from his wife. In fact, Isobel Tashiro sued her husband for divorce, claiming that since Pearl Harbor he had grown “sullen and remorseful” and had been cruel toward her and exposed her to “indignities.” In a letter that was attached to her court file, a Catholic priest, Rev. Joseph MacGrath of Miami Beach, endorsed her position and recommended that she separate from her husband (despite the Church’s formal opposition to divorce). Circuit judge Paul O. Barns granted the divorce in December 1942.

Hostile media reports, reflecting wartime racial prejudice, made no mention of Tashiro’s military service, and instead emphasized the end of the marriage of an American woman and a “Jap.” In 1943, following Aiji’s divorce, his sister Aiko Tashiro, who had returned to the United States following several years in Japan, joined him on an extended visit to North Carolina.

In February 1942, following his return to civilian life, Aiji was hired as landscape architect for the Howard-Hickory Nureries. He also was a registered surveyor. In 1945 he began a partnership with architect D. Carroll Abe at the firm of Abee and Tashiro. Through his work with Abee, Aiji received his architectural license, becoming one of only a handful of Americans to be licensed both for landscape and architecture. During this time he performed design services for the Broyhill ad Stephens families, two influential local families.

The firm of Abee and Tashiro was dissolved in 1952. In 1956 Aiji joined with a young architect, Allen J. Bolick, to found a new architectural firm, Tashiro and Bolick. At the end of 1958, the partnership of Tashiro and Bolick was dissolved. Aiji decided to go out on his own as both an architect and landscape architect. At the tail end of 1959, he moved his office (now called Aiji Tashiro and Associates, Architects) to North Wilkesboro, NC, where he continued his practice.

Aiji resisted being pigeonholed as an expert in any one aspect of design work, preferring to take on a wide variety of projects, clients, and challenges. He designed many types of buildings, not only in North Carolina but also South Carolina and West Virginia. According to his obituary, he built ten Northwestern Bank branches, two factories for the Blue Ridge Shoe Company and numerous additions to schools in Wilkes, Allegheny, and Ashe counties.

He also worked as a landscape designer. For example, in 1955 he received the contract to draw up the master plan for landscaping and beautification around a General Electric plant under construction near Hickory. Two years later, he helped plan the beautification of the Hickory Junior High School. He also produced large-scale landscape projects such as masterplans for Christian assembly grounds for Black Mountain Presbytery, Southeastern Christian Assembly, and the Evangelical & Reformed Church.

Among his most renowned buildings was the Lee and Helen George House, constructed in 1951. Lee George and his siblings worked for their family business, the Merchants Produce Group (known today as Alex Lee, Inc). Aiji worked closely with Helen George, his sister-in-law, to design and construct the George family home, a one-story house whose design bears the mark of Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian style. (On April 24th, 2012, the home was added to the National Register of Historic Places as a notable example of modernist architecture.)

Even as he prospered professionally, Aiji took steps to rebuild his personal life and recover from the trauma of his wartime divorce. In September 1946, he married a local woman, Florence Ruby Boyd. The two would remain married until her death in 1977. Over the half-dozen years that followed their wedding, the couple would have four sons, Arthur, Stephen, Eugene and Richard.

While the demands of running a business and raising a family left him little leisure for literary pursuits, Aiji did contribute an article to the Christmas 1951 issue of the Pacific Citizen on Japanese American architects (he was recruited by his sister Aiko, who also contributed to the volume). Much later, in 1976, his short story “The Letter” won a prize in the “Laurel Leaves” competition of the Appalachian Consortium. Throughout these years, Aiji made occasional public speeches. For example, in 1947 he addressed the state gardening convention in Asheville, NC on flowering shrubs. In 1953 he addressed the Garden Department of the Charlotte Women’s Club.

As the only Japanese American in Western North Carolina for much of his time there, Aiji was able to make a place for himself in the community both in professional and personal terms. One way that he bonded with his neighbors was through religion. As the son of devout Christians, he continued in the faith. During the 1950s, he and his wife were active in the First Presbyterian Church in Lenoir, and worked with the church’s Sunday School.

In 1965, Pacific Citizen columnist Bill Hosokawa devoted a column to Tashiro’s 1934 essay “The Rising Son of the Rising Sun,” and publicly inquired what had become of Aiji Tashiro. At length Tashiro received word of the column and wrote Hosokawa that he was still “alive and kicking vigorously.” Although Aiji stated that he was distant from Nisei activities, he admitted that he would be pleased to find a Nisei to join him—thereby signalling his continuing sense of attachment to Japanese communities:

“By way of closing, I would like to find a Nisei young man to associate with me in practice and ultimately take over, if there should be one oriented toward smalltown practice. I cover a hundred mile area, am the only architect in the county, and have a diversified practice that includes schools, churches, residences, banks and what have you….”

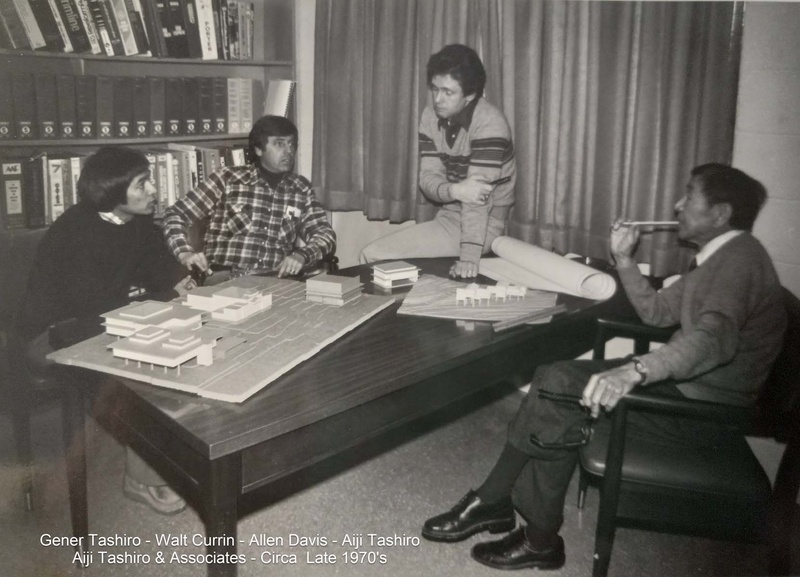

While Aiji seems not to have had any Japanese American takers for his employment offer in the Pacific Citizen, his son Eugene (Gener) Tashiro, who received an MA in Architecture, joined him in the 1970s and eventually inherited the practice, which closed in 2008. Aiji officially retired around 1985, but continued to work part time. He died in 1994.

Aiji Tashiro was a remarkable man—a gifted architect and designer who was also a fine litterateur. His buildings deserve further study—as do his writings. Not the least amazing thing about him was his choice to make his life in North Carolina, a region where he had no Japanese community to provide support. His independent spirit and power of self-expression are noteworthy.

© 2024 Greg Robinson