Nestled underneath the grandstands at the Washington State Fairgrounds, across from the regionally famous Fisher Scone stand, there is a new exhibit opening in 2024. Organized by the Puyallup Valley chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League, the Remembrance Gallery stands as a powerful testament to the 7,500+ persons of Japanese descent who were incarcerated at the fairgrounds in 1942. Many Japanese Americans in the area avoided going to the Fair for decades, finding the memories too painful.

Though a memorial statue by George Tsutakawa is also located on the fairgrounds, the new Remembrance Gallery is centrally located just steps from the main entrance to the Fair, and less than a block from the parking lots that included a lot of the area where “Camp Harmony” was—the largest concentration camp for Japanese Americans in Washington State.

The Gallery has been close to 7 years in the making. In 2017, the community marked the rededication of the Tsutakawa statue. In the intervening years, the members of the planning committee raised $2 million, worked with survivors and descendants and designers and builders and historians. And the results of their work are about to be unveiled for a new year of thousands of visitors at the Fairgrounds.

The Gallery itself is fairly small, but packs a powerful interpretive punch, reminding visitors of their proximity to an important piece of American history. Outside the gallery there are wooden walls featuring windows framing black-and-white historic photos of life at Camp Harmony. Above the gallery there are concrete cracks framed with gold, honoring the Japanese art of kintsugi.

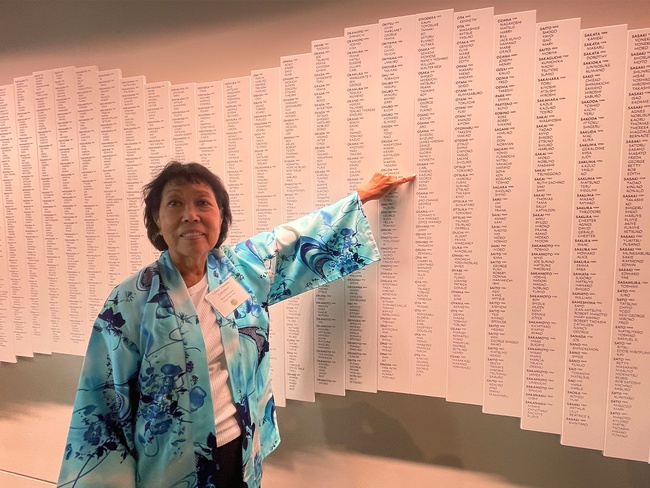

The centerpiece of the gallery is a full wall featuring an undulating shape of Japanese and Japanese American names with government-assigned wartime family numbers. The cloud is meant to remind visitors of the Puyallup River and the White River—nearby geographic features that the Japanese immigrants and descendants would have known, and that the community visiting the Fairgrounds might recognize. Perhaps in keeping with the desire that a memorial should be living, the display wall is responsive: it lights up in response to the motions of visitors. Though my family is not originally from the Seattle area, it was still moving to find the names of literary ancestors, Japanese American writers John Okada and Monica (Itoi) Sone.

To the left of the memorial wall there is an informational display including an overview timeline, photos, and interactive touch screens where visitors can look at different stories, maps, and listen to oral histories of those who were incarcerated at the fairgrounds.

To the right of the memorial wall, there is a replica of a barrack designed to resemble the stark living conditions. Visitors can step inside the barrack replica and feel how small the living quarters were, and listen to recorded sounds of coughing and babies crying. To complete the tableau, a human form is seated on the bunk bed, and I was startled to realize that it was a mannequin. It’s a powerful place that conveys just as much as, if not more than, the informational display opposite the gallery.

At the community preview of the gallery in mid-August 2024, I spoke with three core members of the small but mighty planning committee from the Puyallup Valley Japanese American Citizens League, all Japanese American: fundraising chair Liz Dunbar, project manager Sharon Sobie Seymour and Chapter President Eileen Yamada Lamphere.

“I’ve heard so many great stories today,” said Liz Dunbar, as she took a break from the registration desk. “As Eileen [Yamada Lamphere] says, there’s 125,000 different stories…People saying, ‘I was born here, and this is where we were under the grandstands and we moved to this other area.’ Someone saying, ‘Well, I wasn’t born here but I was born in Minidoka, so I was probably here…in my mother’s womb.’

“It’s been amazing,” she added. “And to see how it’s really touched people. And that’s been very meaningful. And makes it all worthwhile.”

“I am absolutely overwhelmed with emotion of course, in addition to just being downright tired,” said Sharon Sobie Seymour. She is an event planner, and planned the successful 2017 community commemoration at the Fairgrounds. “Sometimes it feels like it’s been a long journey… we started in 2017, so you know, when you look at it that way, it seems a few years ago. But I will say that I think we’re supposed to be here. I think this was supposed to happen. You know, we made it through COVID, there was a little shaking and then [we thought] maybe we weren’t going to, and we did. And nothing stopped us.”

“I think what was extremely special was when my mom got to come,” she remarked. “In fact, she wasn’t doing well. She’s 96. And she says, ‘I’m going to go if I have to hitchhike.’ She got better, and we were able to bring her. And she saw her brother’s name. And saw the horse stall [portion of the exhibit], which was what he was in. And she said, ‘Finally.’”

Seymour’s goal is for as many visitors to the Gallery as possible. “The Fair gets a million visitors a year. I want a million people here, they better know about this after they get their corn dogs and before they take the rides, we just want them to be aware…You are standing on an original confinement site. Actually, if you parked on any of the parking lots, you parked on the site [where people were incarcerated]. And it’s not to make people feel bad or anything, just to make them aware. They have to be aware that this is what happened, this is what exists.”

After working at two preview events and stopping to speak with many community members, Eileen Yamada Lamphere, Chapter President, was similarly exhausted but full of energy speaking about the project. Her mother’s family, two branches of it, were at Camp Harmony. When asked how she felt about the opening, she was thoughtful. “It’s almost celebratory, although that’s not the right word because it’s sacred. The names that are on the monument, every single one of them was a person on the fairgrounds. So there’s not a reason to really celebrate.”

“I hope that survivors that come and see it and their descendants feel that we have honored and acknowledged, in a respectful way, their wartime experience. A lot of technology and part of that was deliberate because we know that that’s how the young people learn. They don’t open up a book anymore. So as much as you could touch or scroll, expand, that’s what’s going to catch the young people’s attention and maybe that’s the best way of learning on the device. But we have to educate the young people or else this could happen again. And we’ve already seen echoes of that.

“So three things that we’re hoping that people walk away with from the gallery visit. One is to acknowledge the over 7,500 that were imprisoned here. Number two, that they realize that 1942 isn’t ancient history. That discrimination, the hatred towards any people of color, started a long time ago. And continues on. And [three,] there is a legacy of in Japanese they call it gaman, being able to set something bad aside and move forward. I think that’s the biggest legacy of our ancestors, is [that] in the face of the worst tragedy they always find a path forward, over, under, and through. I think that sometimes that’s an example of what is missing in our contemporary generation.”

Yamada Lamphere’s background as a teacher was evident as she continued. “I think the most rewarding part of it right now is, now that we’ve had some visitors come through for the soft opening, to see their expressions, seeing what is catching their eye, is that this is not just a memorial. It’s an educational place. This an educational place, a center, that hopefully teaches…and hopefully teachers and students will learn.”

© 2024 Tamiko Nimura