Lorene is my first name. My mother chose my name for me. She liked the sound of the name, but not its typical spelling “Laureen” so she says she changed it. It wasn’t a familiar name especially in classrooms where most girls had names like Cathy, Susan, and Cindy. Most people thought it was a boy’s name and would pronounce it like Lorne or if they knew it was a girl’s name they would say Lauren. My last name Oikawa was even less familiar, and most people would not even attempt to say it. They would look at their lists in confusion. Those who did attempt to say it would laugh out of nervousness or mumble “it’s a hard name” or breathe a sigh of relief when I would call out and identify myself.

When I was younger I would cringe, dreading when names were being called out from a list.

Now that I’m older, people still get my name wrong, but I look upon it as an opportunity to educate, inform, and sometimes entertain.

I remember running into someone at a social gathering and she introduced me as Okinawa. I corrected her and said it was Oikawa. Her impulsive response was, “No, it’s not.” And then seeing the surprised look on my face and realizing what she said she laughed, and said “Oh, I guess you would know your own name. I always thought it was Okinawa.”

I told her that Okinawa is an island. My name means big river, but there once was an Oikawa island. My father’s side of the family came from Japan in 1906 on a ship called the Suian Maru. They were fishers and boat builders. They, along with the others who were on that ship, settled in Vancouver on the Fraser River and built up colonies on two islands they named Oikawa-jima and Sato-jima. Jima means island in Japanese.

During World War II, the government declared all people of Japanese ancestry “enemy aliens,” took all of their property including businesses, farms, homes, fishing boats, and vehicles, and incarcerated them away from the coast. The racism intensified during this period and they even took the names of the islands and changed them to Don Island and Lion Island. It wasn’t until 1949, four years after the war ended, that anyone of Japanese ancestry was allowed to return to the coast. Many did not return; there was nothing to return to.

When I was growing up, I would visit my maternal grandparents in Slocan, a small town in the interior of British Columbia. Their house was small, but my grandmother kept it clean and she looked after a huge garden which produced a bounty including Japanese cucumbers, eggplant, carrots, tomatoes, peas, beans, onions, and gobo. I never thought much about why they were living there and why the contents of their house seemed to originate in the 1950s. It wasn’t until I was an adult when I found out about the internment and then I realized they had to rebuild their lives. They could take only two suitcases with them when they were forced to leave their home on Vancouver Island. They had to stay in animal barns in Hastings Park in Vancouver before being shipped to the Kootenays, the southeast part of the province, and they remained there until my grandfather died.

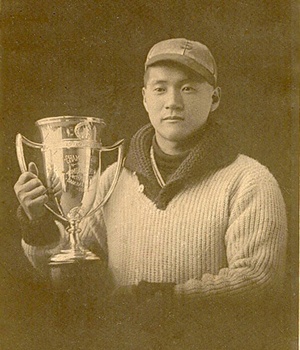

My grandfather was Kenichi Doi. He was born in Cumberland. My mother’s side of the family came to Canada in the 1800s. Four brothers travelled from Japan to the US. Two of the brothers didn’t like it there and made their way up to Canada. They settled on Vancouver Island in the village of Cumberland which is in the northern part of the island. My grandfather worked in the mines as a boy, then in the lumber mills, and then longing for excitement he became a faller. But his passion was baseball. He was a well-known pitcher and was recruited by the Vancouver Asahi baseball team.

My mother says my grandfather was the first born son which is why his name has ichi (number one) in it. I don’t remember anyone using his Japanese name. He was called Ken. My grandparents gave all of their children English names with a Japanese middle name. I think because they wanted to ensure that their children would fit in.

Sometimes when I am at events, the host will ask how to say my name before introducing me. I tell them Lorene rhymes with Irene, and to think of my last name as consonant-vowel pairings. I’ll say out loud, O-i, sounds like oy; k-a is ka; and w-a is wa. Put it together and you get Oikawa. They usually laugh and say Oy!

If people are having a lot of difficulty with my last name, I will sometimes tell them I’m Irish. They will give me a puzzled look, and then I tell them that on St. Patrick’s Day, I drop the “i” from my name and then I’m an O’Kawa. One woman told me that it was the best way for her to remember my name.

At times when I was a child I would sometimes wish for a simpler name so that I wouldn’t stand out.

Now, I see how my names are inextricably linked to my family, my ancestors, and my history. I am a fourth generation Canadian, British Columbian, and I am connected to people and places around the world. And I don’t want any other name.

* This story was developed during the Nikkei Names workshop held at the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre in Burnaby, BC, Canada on July 26, 2014.

© 2014 Lorene Oikawa