For the column’s inaugural post, we wanted to begin with the theme of place, location, and community and to highlight two veteran poets—Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Nisei poet based in San Francisco since 1962, and Amy Uyematsu, Sansei poet and native Angeleno. We are excited to begin with two writers who dedicate much of their creative focus and livelihood to poetry and who have had an influence on so many. Cheers to what their poetry uncovers…

—traci kato-kiriyama

* * * * *

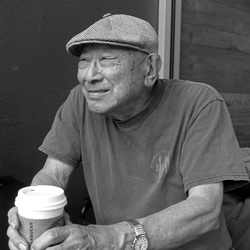

Born in Sacramento in 1922, writer and actor Hiroshi Kashiwagi was incarcerated at Tule Lake Segregation Center during World War II. His publications include Swimming in the American: A Memoir and Selected Writings, winner of American Book Award, 2005; Shoe Box Plays; Ocean Beach: Poems; and Starting from Loomis and Other Stories.

SHUNGIKU

edible chrysanthemum

from the garden

I bite it thoughtfully

and the mint taste

spins time and distance

until I’m face to face

with my Yamato origin

AT TUOLUMNE

The lights go out in the tents,

And the daytime noises cease.

Beyond the tips of the pointed trees,

I can see the night sky.

It is warm inside the sleeping bag.

Tuolumne River is louder at night.

Soon there is only the sky, the trees,

the river and a man in a sleeping bag.

In the morning,

I wake up to the caress of

pine needles on my face and hair.

TULE LAKE MONUMENTS

Castle Rock and Abalone Mountain

and the dry lake bed where tules grow

are timeless, immutable monuments

that bear witness to our confinement

they know and remember for us

the history of our sorrow

dust storms

frequent

powerful

relentless

we endured

we survived

our spirits

unyielding

ultimately

triumphant

OCEAN BEACH

I like

the smell

when I get off

the bus

like the taste of

octopus

of course

it’s the sea

and I know

I’m home

* The poems above are copyrighted by Hiroshi Kashiwagi.

* * * *

Amy Uyematsu is a Sansei poet and high school math teacher from Los Angeles. She has five published collections: Basic Vocabulary (Red Hen Press, 2016), The Yellow Door (Red Hen Press, 2015), Stone Bow Prayer (Copper Canyon Press, 2005), Nights of Fire, Nights of Rain (Story Line Press, 1998), and 30 Miles from J-Town (Story Line, 1992). Her work can also be seen in many anthologies and literary journals. Currently she teaches a creative writing class at the Far East Lounge for the Little Tokyo Service Center.

30 MILES FROM J-TOWN

1

dad was a nurseryman

but didn’t know that sansei

offspring can’t be ripped

from the soil

like juniper cuttings.

2

we were fast learners

we spoke with no accent

we were the first to live

among strangers

we were not taught to say

ojichan, obachan

to grandparents

we were given western

middle names

we collected scholarships

and diplomas

we had a one word japanese

vocabulary:

hakujin

meaning: white

it became my dictionary.

3

and in the summer when

girlsmooth cheeks turn mexican brown

we were given the juice of a lemon

an old country notion, its sting should return

us to our intended feminine selves

4

if you’re hip in l.a. you eat

sashimi at least

once a month you know

the difference between

fresh and saltwater eel you cultivate

a special relationship with one

sushi chef you call

each other by first names-san.

as for me

I had sashimi on hot august nights

steaks grilled rare, 5 cups steamed gohan,

maguro never mushy sliced thick red,

and while the tongue burns sweet

from the mustard of wasabi,

mom brings in wedges

of moist chocolate cake

for cooling.

5

they didn’t force the usual

customs on us.

no kimonoed dolls in glass cases

no pink and white sashes

for dancing the summer obon

we weren’t taught the intricacies

of folding gold and maroon squares

into crisp winged cranes, but

we never forgot enryo

or the fine art of speaking

through silences.

6

every two or three years america goes asia exotic

rising sun t-shirts and headbands

rock stars discover geishas and chinagirls

and asian american women become more desirable

in fashion

almost a status symbol in some circles

be careful it doesn’t go to our heads

in videos blond hero always rescues us from yellow man.

7

quickchange sansei

we can talk cool whether we’re from

southcentral lincoln heights or the flats

and even when we’re not

we can say a few pidgeon phrases

a crude japanese english

offered to grandparents

before they die,

we can fool

sound just like an american

over the phone,

and in public places

we usually don’t talk at all.

8

on important occasions

dad drove us into j-town

through the eastside barrio

past the evergreen cemetary

his sister and brother

never knew manzanar

kanji and english inscribed

on their gravestones

then over the first street bridge

into nihonmachi

this was the center

this was the lifeline

9

I go to japanese movies

whenever they come to town

curious I see few and fewer like me

there are muscular young black men

and white men with indoor complexions

some don’t even need subtitles

but they cannot know

I have to be here

I must spend these three hours

with faces voices

warriors farmers lovers

I would know

and to my soul

these quivering notes

of the shakuhachi

melodies I have heard long ago

10

grandma morita had no time

to learn how to drive the machine

but she took us by bus

to woolworth’s

a dollar each to buy treats

for two girls who could never

talk to her about dreams.

* This poem was originally published in 30 miles from J-town in 1992

and copyrighted by Amy Uyematsu.

THE WELL

Imagine a mountain whose name is heart.

At the throat of the mountain

they fill a well

with so many stones

it can hold nothing more.

They’d never heard of

the mountain named heart,

Kokoro-yama, til they were taken

as prisoners to Heart Mountain.

Imagine a heart big enough to be called mountain.

A mound of stones,

too many to count, remain—

each inscribed

by a different hand,

each crying out.

Some simply reveal

the writer’s name—

Shizuko, a woman,

or a family known as Osajima.

Most of the handpainted

rocks carry a single kanji—

snow wind cold sky

shame home bird.

—For the 12,000 Japanese Americans

interned at Heart Mountain, Wyoming

* This poem was originally published in Nights of Fire, Nights of Rain in 1998 and copyrighted by Amy Uyematsu.

© Hiroshi Kashiwagi; © 1992 & 1998 Amy Uyematsu