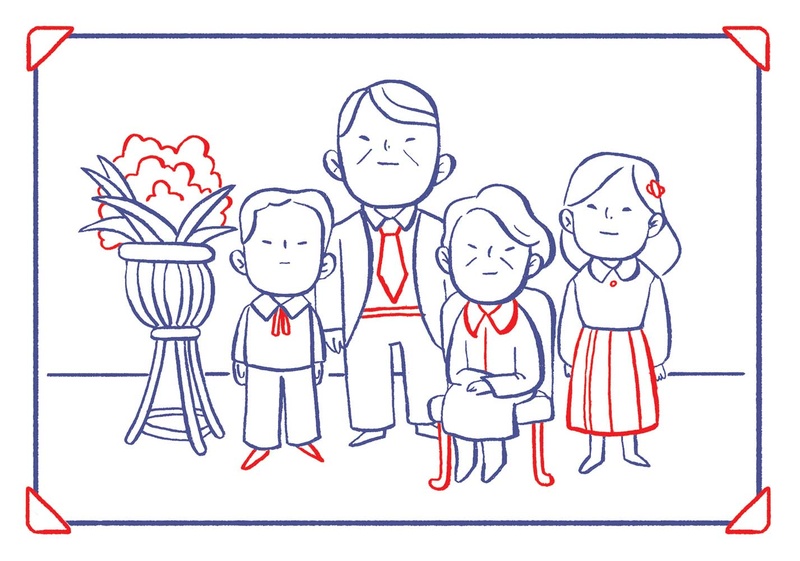

Last year, the illustrator Diana Okuma Oshiro won the third call for editorial projects organized by the APJ Editorial Fund for her series “Memories of Japanese Immigration,” and she did so with a graphic proposal: a book composed of illustrations and very brief.

Nikkei portrays various situations, from those he heard from his grandparents about the first Japanese immigrants, to those that are part of his daily life and that he addresses with humor and wonder from his sansei perspective. We talked to her about what it means to be a Nikkei and her work as an illustrator.

* * * * *

What encouraged you to participate in the call for editorial projects?

I had heard about this competitive fund for publishing projects two years ago and I was encouraged to participate this time. I wanted to share my notes about curious things about the Nikkei community. I studied from Monday to Friday at a Nikkei school and, on weekends, I played sports at Nikkei institutions. When I started my higher education, I suddenly left this environment and was able to learn about other types of customs. So, there I realized that what I saw as normal or common practices were not so normal, and I decided to start writing down interesting notes about it in a little notebook.

What does it mean to be Nikkei for you?

I will always be in search of defining myself as a Nikkei, but it is becoming more and more concrete. I think that throughout our lives we will constantly doubt who we are, not only as a Nikkei, but as a person in general. But when making this publication, even in the editing process, I realized many things that helped me define myself a little more. So, I am a Nikkei Peruvian, and I already feel more confident. Doing this project has helped me find my way. Doing something I always wanted also helped me define myself much better.

In your book you present situations that many Nikkei go through, have any of them happened to you?

Half of the things I have illustrated have happened to me; others are experiences of Nikkei friends or family. For example, when friends from high school or other places started coming to my house, they would ask me if they had to take off their shoes. It happened to me at least five times.

How do you observe the Nikkei community from your sansei perspective?

I feel like it's opening up a little more. Before, the Nikkei always socialized with each other, but now I see that young people are more open to interacting with everyone and that their families and the communities to which they belong want to know more about other communities. I feel like it has changed from how it was when I was 10 years old, that things were a little different, everything was a little more closed. I believe this change has been driven by the internet. This helps people communicate more and share their experiences through social networks. Communication is a little more fluid, and we don't just see what we have in our community.

How do you define your work as an illustrator?

I am a career graphic designer. I studied design and did branding , and in the end I was in animation and character design, but I always came back to telling stories. Since I was little I liked comics, manga and animation that I saw on TV. There was always that pleasure of drawing and telling. Without realizing it I always wanted to do that. I think Nikkei encourages me to do more projects like this.

What inspires you when you draw?

More than an author, I am inspired by style. I take classes at an online school, where teachers who are artists who work in an animation studio teach. They do storyboarding , painting, etc. All the advice they give in class is what encourages me to continue trying. Furthermore, I follow a page called 'School listen' a lot, because they encourage people to move forward, to study, to continue drawing. I would like to retire doing illustration, because I like to tell stories through it.

What elements do you rescue from Western style and Japanese style?

I like many things from both worlds. About the Japanese, what I like is the simplicity of the lines, but also the looks, which are very beautiful, and the proportions of the head and the more stylized body. Of Western-style illustrators, I like the volume and variety in the representation of their characters, they are not afraid to experiment and, in those cases, the expressions are more real.

Who are your artistic references?

I have many. I love Mike Mignola, who is the creator of Hellboy. I really like Nicolas Marlet, an illustrator who has done character designs for Kung Fu Panda, for How to Train Your Dragon. And generally they are artists who work for animation, who work to tell stories, create characters and everything to create a film, a short, a series. And in the case of manga, I really love the work of Eiichiro Oda, the creator of One Piece , because he is a person who has been able to create an entire universe, and he also designs his stories very well. The ideal is not to learn just one style, but to learn everything.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 118, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2019 Texto y fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa