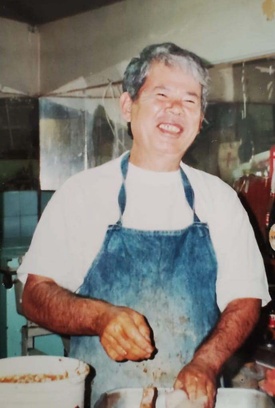

Choko Tsukayama is 78 years old and has extensive experience in Nikkei cuisine, the kind that was born in inns and family businesses and that he learned by watching. YouTubers have made their stuffed potato viral and several restaurants in Lima serve their soba and ramen noodles. And if we talk about Okinawan food and okwaashi, as the cakes are called in the Uchinaguchi language, the Tsukayama surname is undoubtedly the main reference since 1965.

KWAASHIYAA TSUKAYAMA

Choko was 16 years old when she worked at Kwaashiyaa Tsukayama. “My uncle's pastry shop did quite a bit of business,” says Choko. There was high demand for okwaashi and soba noodles and ramen in the 1950s, thanks to the large Okinawan colony that lived in Lima. “They sold like 50 kg of soba pasta every day!” he remembers.

Choko learned the secrets of dough for making okwaashi and artisanal noodles from her uncle Chotatsu, although he never explained it to her. “He just said 'watch and learn'.” After countless trial and error attempts, Choko managed to master his uncle's technique.

In addition to okwaashi , Choko Tsukayama also became known for Chaplin and senbei miso and kion cookies, which he prepared on his own in the 1960s and 1970s. Over time, Choko became one of the three partners of Pastelería Tsukayama , as Kwaashiyaa Tsukayama was also known, along with his uncle Chotatsu Tsukayama and Augusto Sesoko, all born in Yonabaru, Okinawa. But the crisis of the 80s ended up dissolving this society. Chotatsu returned to Japan, Sesoko kept the pastry shop and Choko started a new restaurant.

THE RESTAURANT OF THE JR. LETICIA

In the early 80s, Choko opened a restaurant in Jr. Leticia in downtown Lima, specializing in Creole food. But the economic crisis of that time threatened to liquidate countless businesses and the migration of kasegi to Japan promised a better future. Forced to work in Japan, Choko left his wife Keiko and daughter Erika in charge of the business until his return.

The restaurant operated for 15 years. “We left Leticia when the ojii called us,” remembers Erika, who at that time was studying Architecture at the university and helped in the store in her free time.

SUKI, THE LAST BUSINESS IN THE CENTER OF LIMA

When he returned to Peru in 1990, after working two years in Japan, Choko dedicated himself completely to Suki, which was originally a bar owned by ojii Chobin, Choko's father. The bar was located a few meters from Pastelería Tsukayama and changed its status to a restaurant with the arrival of Erika and her mother Keiko, at the request of the ojii.

Erika decided to name it Suki, which comes from the Japanese “to like,” because customers liked the restaurant's homemade seasoning, she explains. Choko learned Creole seasoning from ojii Chobin and ojii learned it from Santamaría, a store employee who worked for the Tsukayamas since he was 17 years old. Keiko, his wife, learned the secrets from her mother-in-law Toshiko.

In 2008, Suki passed into the hands of Erika, who had left her career for cooking. But the crisis generated by the COVID-19 pandemic and other factors forced Erika to close it last year. By then, Uncle Jimmy was already working.

UNCLE JIMMY

When he retired from Suki, Choko opened El Tío Jimmy in 2000 in the Magdalena market, stall 302.

Far from the Center of Lima, Choko had found the place of his dreams in Magdalena, since it was closer to the house and inside a market. “Chaufa rice and noodles” was the stand's main dish, until Choko discovered the competition's stuffed potatoes.

The line of people that formed daily at the neighboring stall, the same one that was visited by the renowned chef Gastón Acurio, aroused Choko's curiosity. “What are those stuffed potatoes about?” he asked himself.

As if he were a culinary spy, Choko bought four potatoes from the competition and tried them. He created his own version and invited his market neighbors. “My parents know better,” was the verdict. Weeks later, people were already lining up for Uncle Jimmy's potatoes after they went viral thanks to YouTubers and influencers.

Uncle Jimmy went so viral that the place was too small. In 2021, Erika opened El Tío Jimmy 2 in the Bolívar market in Pueblo Libre, stall 32A. Together with Eduardo Toguchi, her husband and well-known radio host, Erika plans to soon open a third Uncle Jimmy in the same market.

In addition to the hearty stuffed potatoes and coated sweet potatoes, El Tío Jimmy offers a varied menu, which includes tempuras and sata andagi “bombitas,” as well as osushis, onigiris butamiso (pork with miso) and chasiu by weight. Available to order and to go, there are Japanese and Okinawan dishes such as tonkatsu, yasaitame, goya champuru and iricha , among others.

Ramen and soba soups are also sold to order and to go, as well as a kilo of 100% handmade noodles. And as an old Okinawan saying goes, “all parts of the pig are eaten, except the grunt.” Uncle Jimmy also offers ashitibichi soup, mimiga and the sweet rafuteen pig.

What is Choko's secret? “Work quietly, without talking,” he answers. “Once I start working, I don't want to talk to anyone,” he adds. But a comment from his wife Keiko reveals to us what could be another secret: “My husband and I have been working together for more than 40 years.”

From Okinawa to Peru, passing through the Philippines and Bolivia

Chobin and Toshiko, Choko's parents, immigrated to the Philippines in search of a better future. After about 8 years, the Tsukayamas were forced to return to Japan when it lost World War II. Chobin worked in the Philippines cutting wood in the mountains and Toshiko took care of her three children and one who was already on the way, who was Choko.

But the war had brought poverty to Japan and the Tsukayamas sought a new destiny. In 1961 they traveled to Bolivia, but it was only a temporary destination. Until the 1960s, Peru still restricted the entry of Japanese as a result of the post-war period, a measure that made the situation difficult for the Tsukayamas, now with 9 children. At that time, Choko was 16 years old.

After four years living in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the Tsukayamas got the long-awaited “call” from Uncle Chotatsu, who had a pastry shop on Capón Street, in Lima. The Tsukayamas arrived in Peru in 1964, under the yobiyose imin modality or “immigration by calling of relatives.” While in Peru, Choko knows his calling.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article published in Kaikan magazine No. 130, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2023 Milagros Tsukayama Shinzato, Asociación Peruano Japonesa