“ Komorebi ” means “sunlight filtering through the leaves of trees.” It was the word chosen by five Nikkei artists—Sachiko Kobayashi, Meche Tomotaki, Tamie Tokuda, Daniela Tokashiki and Nori Kobayashi—to title a group exhibition at the Peruvian Japanese Cultural Center in which they addressed their ethnic identity and their relationship with Japan, a country with which they are connected through the stories of their ancestors, filters of a distant past that only survives in memories and history books, of a Japan that no longer exists.

The name was proposed by Nori. He liked “ Komorebi ” for its sensoriality, for that play of light and shadow that it denotes. “It is a metaphor for how we are in relation to Japan, that we do not have direct knowledge because we are not Japanese,” she explains.

The five have participated in the Nikkei Young Art Salon, an exhibition that the Peruvian Japanese Association organizes every year. The story could have ended there, but they felt that they still had things to express, that the issue of identity was not fully expressed, so they decided to get together and create their own space.

The hall made them friends and during their talks they realized that — as sansei — they had lived similar experiences. The families looked alike. His grandparents were his first connection to Japan.

However, beyond the family sphere, the majority did not have a close relationship with the Nikkei community. Thanks to the salon, they approached her and discovered that what they considered personal and non-transferable experiences were actually common.

“I was very surprised to know that the things that I thought had only happened to me are repeated in every family, at least within the five of us. For example, knowing that there are words that as a child you think are in Spanish, but when you grow up you find out that they are in Japanese. It's something you tell your friends at school, but no one understands it. From there you find out what happened to everyone. I was surprised to learn that we were experiencing the same family process,” says Sachiko.

For Tamie, the salon meant expanding the boundaries of her Nikkei identity. “It felt like an identity of mine, it wasn't something I could share with other people. It's great to feel that this corresponds to something bigger, that I could share all this with other people. Something that I assumed was very mine, belonged to several people.”

In Nori's case there was a kind of reconciliation. “I was distant from the Nikkei community. There was a certain rejection, so to speak, because there is always this thing that you are 'Chinese' and you try to fit in (in national society), 'I am just like you'. So there was always something like denying my Nikkei identity, and with the salon I had the opportunity to analyze it a little more and go deeper into the topic. “I have been able to assimilate things better,” he says.

“I was also a little distant from the Nikkei community,” Meche intervenes. The experience in the salon was fruitful because in addition to bringing her closer to her roots, she was able to meet people who were very diverse with respect to their identity, “some who had it super-rooted, who were super attached to the community, and others who had nothing to do with it, who It was the first time they set foot in the (Japanese Peruvian) Cultural (Center).”

Diversity, instead of dividing, enlarges the community. It all adds up. “It's part of all of us really. I thought it was cool,” says Meche.

Something different happened with Daniela, since she has been “super into the community” since she was little. So deep inside that I felt that the roll of identity was exhausted, that there was nothing left to discover.

However, the salon allowed him to meet Nikkei with different experiences, to immerse himself in other realities that broadened his perspective. “It's cool to share experiences because you say 'there were more Nikkei than I knew.' I talked with people who had not lived the same as me, Nikkei who do not frequent here (the CCPJ). How enriching. It is very refreshing. I thought I had touched on all the Nikkei songs, but suddenly I say 'wow, there are more things.'

“You always find something else to say,” adds Daniela, one of the two girls who have had the opportunity to travel to Japan. The other is Meche.

Daniela discovered that her mother's idealized Japan, forged by the stories of migrant ancestors, does not coincide with real Japan.

ART TO EVOKE

The five works are nourished by family memories. “Souvenir”, by Meche Tomotaki, contains, for example, pieces alluding to her father and grandfather's business selling baby clothes, as well as games with her ojiichan, with whom she was very close when she was a child. He made origami and she painted the mouths of the figures; In the playful world they had both created, a painted mouth was a fed mouth.

Her family's memories are like trips, stops on a personal itinerary that shape her identity, that of a sansei who fondly remembers the grandfather who always told her the same story, in Japanese and Spanish.

Tamie Tokuda created “Family Puzzle” from a photo she found of her ojiichan in her native Shimane in 1929. In the image he appears with his grandparents, his mother, his sisters, etc. The discovery of the photo activated a search for her origins that led her to use another image, in which her grandfather also appears, but this time with the family he formed in Peru.

The puzzles, assembled from the two photographs, have interchangeable pieces that combine past and present, Japan and Peru, an intergenerational mix from which comes a family legacy, the basis of identity.

“Roots”, by Sachiko Kobayashi, delves into the origins, exploring the depths that serve as a foundation for building an identity. The work is composed of a set of roots drawn on papers, independent and on various levels, but all forming a unit.

The idea is not to limit yourself to Nikkei. Researching your ancestors is a universal experience. “The search for identity is not a way to separate ourselves, but rather to find common links,” explains Sachiko. The drawn roots also refer to the plants that have been part of her life since she was a child, and that evoke relatives and Nikkei chakras.

Fish is a central element in Daniela Tokashiki's memories. His family gravitated towards his grandfather's restaurant, Minoru Kunigami, one of the fundamental names in Nikkei cuisine. He dissected fish and exhibited them, fish that inhabited the sea that unites Japan and Peru, a meeting place between the two cultures.

“The catch of the day”, composed of three fish that gain materiality through ceramics, is a tribute to his ojiichan. In the process he encountered technical obstacles that he overcame with inspiration from him. "If my grandfather could achieve so many things, without having the tools that I had, I said to myself 'I can do it too." In the middle of the job she learned that if the instruments are not enough for you, then be more creative.

When you migrate, you don't just take objects. It also carries memories, customs and traditions, all that makes up “The Invisible Luggage” by Nori Kobayashi, which includes the intangible heritage brought by Japanese immigrants. In Peru, the invisible luggage of the Issei —or part of it—was mixed with local heritage, a fusion that is also reflected in their work.

Nori confesses that his original intention was to use elements recognizable by everyone, not so personal, but hey, the family wins, and he ended up using his obaachan or his sister as characters.

FUTURE MISSION?

Art allows us to say things that, due to modesty or other reasons, we are unable to verbalize. Even more so in a human group like the Nikkei, which is not exactly expressive. “That part of me that is difficult for me to express in words, I can do it through these things. I can't tell my parents things like 'how much I admire you', but through these works—it's kind of therapeutic—I can express them, tell them how important they are and how much they are part of my process as an artist,” says Sachiko.

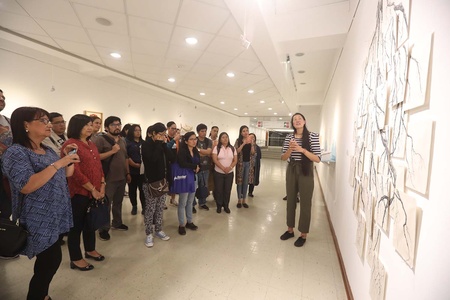

Art has brought girls closer to their families. Daniela remembers how excited she was that her family attended the opening of the exhibition. “They were happy to see that someone is valuing family work.”

When Meche's father saw his daughter's work, he was impressed by how present her childhood memories were: the family business, games with ojiichan , etc.

By rescuing memories of their families and keeping their legacy alive through art, do artists assume a kind of mission to preserve and transmit that heritage?

Tamie wonders. Grandparents leave and with them their memories and customs. What happens if your descendants have no interest in maintaining the family legacy? She says that she has relatives without ties to the Nikkei identity, completely removed from the community, and she feels as if there is a rupture.

"I feel sorry. I wonder what will happen from here on out,” he says. “I have a mysterious mission... or what it will be. I feel like maybe this could die.” For Tamie, it is not without reason that she found the 1929 photo, taken in Japan and which inspired her work, in the trash.

LIVING CULTURE

The Nikkei Young Art Salon has opened an important space to integrate young people of Japanese origin into the community and offer them a vehicle for expression. An enclave that could grow.

For Sachiko, all the windows that open are “super cool,” but she suggests expanding the scope of the artistic manifestations that are hosted to include artists from the most diverse disciplines.

Tamie, for her part, advocates for more spaces for expression. “I feel like there is still a lot to say,” he says. “It is super good that the Nikkei identity evolves from the old portraits and begins to say that it is a living culture, an identity that continues.” The story continues.

EVERYONE FOR EVERYONE

That the five exhibitors of “ Komorebi ” are women is a coincidence. They didn't propose it. It arose out of affinity thanks to the friendship that arose in the classroom. Everything flowed naturally.

Now, unlike the living room, where there is a path laid out, in “ Komorebi ” everything was to be done. That meant more freedom, but also more responsibility.

For the five of them it was quite a learning experience, in a process that included everything from the conceptual framework to the logistical aspects.

If in the room they had agendas with formal calls, here the meetings were organized by chat. If in the room there was a person in charge to whom they reported, here everyone had to be involved in everything and answer to everyone.

They had fears and doubts, wondering along the way if they were going well. However, they managed to carry out the exhibition. Daniela emphasizes that all of them, apart from creating their own works, worked voluntarily. “Each one has wanted to do their part, each one has it in mind, from printing to bringing snacks. “I thought that was one of the coolest things.”

“We've helped each other a lot!” says Tamie.

Of course, although they ran alone, they highlight the role of Haroldo Higa (“an important character”), one of the architects of the Nikkei Young Art Salon, as promoter, advisor and support.

Will there be a next group show? “Twenty years from now, an exhibition at the Jinnai (Center)” (for the elderly), jokes Nori. Everyone celebrates the event. If laughter is a reliable indicator of friendship, then theirs sounds good.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 122, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2020 Texto y fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa