Playing in the ALOHA Baseball Team

Concurrent with the establishment of the Hawaiian Student Society of Chicago in May 1922 was the formation of the ALOHA baseball team; it was mainly composed of members of the Society who were attending colleges and universities in Chicago.1 Tashiro himself played for the ALOHA baseball team as team captain and catcher for a while, while Wilfred Tsukiyama was the pitcher. Both of them had played baseball at McKinley High School in Honolulu.2

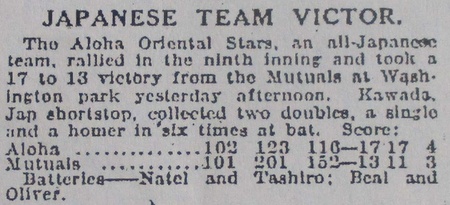

The ALOHA team’s first game was played on May 13, 1922, at Washington Park, against Mayo College. ALOHA defeated their opponent by a score of 7 to 5. According to the Honolulu newspapers, who were delighted by this team in Chicago comprised of Nisei from Hawai‘i and covered the story even though the games were held in Chicago, “The following was the lineup for the new team. Raymond Kong, Herbert Takaki, Isamu Tashiro, Wilfred Tsukiyama, Sanzo Iwamoto, Tomo Ouye, Wong, Yoshio Tanaka, Robert Murakami.”3 Local Chicago Japanese were also very excited when ALOHA was victorious against gaijin (foreigners) on the very first game.4

Their strong record earned ALOHA the right to start playing in the Windy City League in 1924. At this point, they were called the ALOHA Oriental Stars. The players, most of whom were college students, were not just from Hawai‘i, but also from Japan, the Philippines, and the Malay Islands.5

Fostering US–Japan Relations

Around 1926, Tashiro got involved in educational activities for the American public. This included giving talks and lectures on Japan and Japanese culture around Chicago. Tashiro’s first public speech that was reported in the newspaper was at the twenty-sixth meeting of the Walt Whitman Fellowship, held in June 1926, where representatives of all races sat down together and discussed their desire to bring about a better spirit of comradeship among all mankind.

Isamu Tashiro attended the meeting as a representative of Japan, and according to the Chicago Defender, he “pleaded for better understanding between Americans and Japanese. He also discussed America’s intolerant attitude toward all except the American white race, and asked that the pleadings of Whitman be taken more seriously.”6

After US–Japan relations began declining in the 1930s, Tashiro became even more active in his intercultural role. This was due to the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the Shanghai incident in 1932.His lectures were held every month, and usually in churches, but not only in Chicago but also in cities such as Peoria, Bloomington, and Urbana, in central Illinois.7

He believed that introducing Japan and Japanese culture to Americans could promote better Japanese–American relations by establishing “a friendly feeling towards Japan and Japanese” and creating “a greater enthusiasm among Americans to study the Japanese culture of more than two millennia.”8 He received no compensation for his work; yet he considered his work as a noble sacrifice for the betterment of all.

Representing Japan at the World Fair

When the Century of Progress International Exposition was held in Chicago in 1933, Tashiro participated in the opening parade. As the leader of the group representing Japan, he carried the national flag and marched with fourteen Japanese young women in kimonos from both Chicago and the West Coast, and “a few male officials donned in full native costume.”9 A dinner dance party was held at a beautiful apartment facing Lake Michigan to entertain some thirty-five Nisei leaders who had either worked at the Exposition or lived in Chicago. Tashiro acted as master of ceremonies for the evening and showed off his modern version of the rhumba dance as entertainment.10

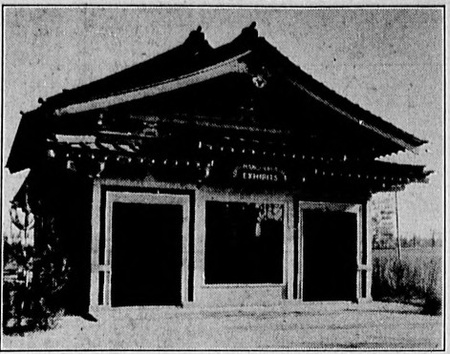

After the Expo was over, Tashiro was instrumental in bringing the specially commissioned Manchurian Pavilion to California.11 The exhibit inside the pavilion consisted of information about Manchuria, provided by the South Manchurian Railway Company. The original plan was to donate the exhibits to the Julius Rosenwald Industrial Museum in Chicago;12 it was to be housed in the reconstructed Fine Arts Building from the 1893 Columbian Exhibition, later called the Museum of Science and Industry.13 However, the building itself needed a new home.

At first, it was planned to donated to Bishop K. Masuyama of Honganji temple in San Francisco, who was a superintendent of the Buddhist mission in North America.14 Later, however, it was actually transferred onto the property of the Sonoma Buddhist Church in Sebastopol.15 Bishop Masuyama named it Enman-ji temple, and it was expected to be a major attraction for the city of Sebastopol.16 Enman-ji temple became a center for the local Japanese community, and still serves the local community today.

Lecturing on Current Affairs

Tashiro gradually built a reputation as a lecturer, one even recommended by the Japanese consul,17 and was frequently invited to speak on current political issues. For example, in Spring 1932, he gave a talk on the position of Japan in the Far Eastern Conflict at the first meeting of the Cosmos Club,18 a student forum organized by the political science department at the University of Chicago for the purpose of acquainting students with international affairs.

By 1935, Tashiro was rumored to have already spent nearly $3,000 of his own earnings on his work as a public speaker, specializing in introducing Japan to the U.S.19 Upon receiving immense praise for his volunteering spirit from a Japanese newspaper reporter, Tashiro responded, “I think it is not only my hobby, but it is my duty to devote myself to the cause of human affairs as an American citizen of Japanese extraction. Before we demand anything, we have to prove that we are worthy American citizens in every respect. Every single one of us has to do our part.”20

Tashiro’s volunteer activities were not limited to the Midwest. Eventually he extended his “territory” to the West Coast and Japan, as he dropped in on the Pacific Coast as well on the way to Japan from Chicago.21 These four locations – the Midwest, the West Coast, Japan, and Hawai‘i – were deeply interconnected in his mind, and provided a platform for sharing his ideals, while utilizing his experiences in each of these locations.

Making Films about Japan

Tashiro returned to Hawai‘i frequently to visit his parents, until they returned to Japan in 1935. After that, he visited Japan every year. However, his trips to Japan were not just to visit his parents and bring back “more shoyu and rice cakes,”22 but to gather the latest information on both contemporary Japanese politics and traditional Japanese culture and arts.

While in Japan, he “photographed in color scenes of flower arrangements, sequences of fashion and of kimono making.”23 In all, he made more than 10,000 feet of color films, such as the scenic film, “The Four Seasons of Japan,”with his own 16-millimeter movie camera. He eventually showed these films to thousands of people at his lectures.24

He interpreted Japanese culture as “a curious blending of the culture of the East and the West.” To illustrate his point, he often showed his audiences a beautifully made zori, a slipper worn for centuries in Japan, with a small rubber heel of American design.25

Tashiro attended the International Teachers’ Conference in Tokyo in 1935. He had another assignment for the trip as well. He was assigned to make an inspection tour of China and Manchuria for the Ford and Chevrolet truck companies.26 When he came back to the U.S. from Japan and Manchuria in October 1935,27 he was invited to show his motion picture films about this trip throughout the Midwest.28

Tashiro’s enthusiasm helped American audiences “discover new meanings in Japanese life.”29 As a natural consequence of these ideas and his ambassadorial spirit, he said that he wished that he could show his Japanese home movies and host goodwill sukiyaki dinners all over America.30

Sharing Japanese Culture

Newspapers reported on many more of Tashiro’s lectures. For example, he lectured on “The Human Side of Japanese Life”31 as part of a free public lecture series hosted in October 1932 by the Chicago Baha’i Fellowship Race Amity Committee.32

At the Women’s Industrial league for Peace and Freedom in May 1937, Tashiro “explained that industrial expansion in Nippon is, in a great measure, credited to the nation’s educators who succeeded in changing the educational system to meet the social changes,” and “paid tribute to Townsend Harris for laying groundwork of Japan’s international advances in industry as well as diplomacy.”33

When a subsidiary organization of the Japanese government, the Japanese Federation of Export Industrial Arts, held an exhibit of 500 Japanese craft pieces such as textiles, pottery and porcelain at the Drake Hotel in February 1937, Tashiro was invited to give a lecture on Japan, with visual aids projected on a color stereopticon.34

Notes:

1. Nippu Jiji, May 31, 1922; The Honolulu Advertiser, June 1, 1922.

2. The Honolulu Advertiser, June 1, 1922.

3. Ibid.

4. Nippu Jiji, June 1, 1922.

5. Chicago Tribune, January 14, 1924.

6. Chicago Defender, June 12, 1926.

7. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21, 1935.

8. Ibid.

9. Shin Sekai Nichi-Nichi Shimbun, June 3, 1933.

10. Shin Sekai Nichi-Nichi Shimbun, September 17, 1933.

11. Shin Sekai Nichi-Nichi Shimbun, November 9, 1933; Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21, 1935.

12. Shin Sekai Nichi-Nichi Shimbun, October 24, 1933.

13. Science, September 10, 1926.

14. Shin Sekai Nichi-Nichi Shimbun, November 9, 1933, Yomiuri Shimbun, February 2, 1934.

15. Shin Sekai Nichi-Nichi Shimbun, November 9, 1933.

16. Nichibei Shimbun, November 8, 1933.

17. Daily Maroon, March 2, 1932.

18. Daily Maroon, March 2 & 3, 1932.

19. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21, 1935.

20. Ibid.

21. Nippu Jiji, October 7, 1936.

22. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21, 1935.

23. Japanese American Courier, September 4, 1937.

24. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21, 1935.

25. Japanese American Courier, September 4, 1937.

26. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, July 4, 1935.

27. Nichibei Jiho, October 26, 1935.

28. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, July 4, 1935.

29. Japanese American Courier, September 4, 1937.

30. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21, 1935.

31. Chicago Defender, October 31, 1936.

32. Chicago Daily Tribune, Oct 28, 1936.

33. Kashu Mainichi, June 7, 1937.

34. Nichibei Jiho, February 20 and March 6, 1937, Chicago Tribune, February 16, 1937.

© 2023 Takako Day