Inspiring Young Nisei

One of Tashiro’s most important concerns was the future of young Japanese American Nisei and their position in the U.S.–Japan relationship. His former teacher Asano described how strongly Tashiro wanted to help improve the situation for young Nisei in Hawai‘i, and mentioned that Tashiro once expressed a desire to go to South America to set up business ventures for them.1

Living at International House

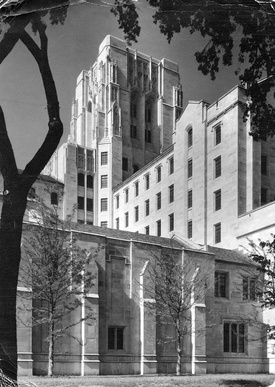

Tashiro inspired young people in Chicago as well. When the International House was built on the University of Chicago campus at 1414 East Fifty-Ninth Street in 1932, he moved into the House and lived in the tower.2 By residing on campus, Tashiro was now close enough to get involved in the activities of young students there. There were students from all over the world living there, and their relationships with their home countries must have impacted their connections and associations with other students.

In April 1933, some foreign student residents expressed their dissatisfaction with the conflicts, unfriendliness, suggestions of “espionage” and “suppression of free speech” at the International House.3 When an editorial titled “Foreign Students Still Lack a Real Home on This Campus” appeared in the student newspaper, the Daily Maroon, Isamu Tashiro was one of twelve people who signed a letter challenging the complaint as a “gross misrepresentation of the opinions and attitudes of most of the foreign students.”4

Tashiro worked hard at the International House to establish friendly attitudes towards Japan and Japanese people, and to create a greater enthusiasm among students (and Americans in general) for studying Japanese culture.5 For example, he took several Japanese students with him to a demonstration of jiu jitsu and he did not hesitate to put on a haori coat and gracefully twist his hands to demonstrate Japanese folk dancing.6 Tamotsu Murayama even joked about Tashiro’s sociability in an international setting, quipping that “perhaps he sings Chinese songs with a Korean accent or Tokyo Ondo (Japanese folk songs)with a Hawaiian accent.”7

It was reported that Tashiro even had a plan “to build a House of Culture on the University of Chicago campus. The house would be typically Japanese to illustrate all phases of Nipponese culture.”8 Some fans of Japanese culture even requested that Tashiro include a tearoom in the House.9 However, no one knows what became of this plan.

Tashiro’s trips to Japan were also meant to benefit the International House. At one point, he expressed that his mission was “to extend the International House scholarship to the Japanese student goodwill tour to the Orient on behalf of the International House.”10 He showed color movies that he made from his Japan photos at an evening program called the “Globe Trotter Salon,” held by camera fans at the International House.11

Connecting with West Coast Nisei

In addition to his work educating the American public and supporting young people in Chicago, Tashiro started making connections with West Coast Japanese. Perhaps he felt isolated in Chicago; the Japanese community was small, and those who did live there were predominately Christian. He may have missed Japanese community gatherings at Buddhist temples.

He visited various places in California on his lecture tour and showed films on Japan that had been made for the Fair, such as Four Seasons of Japan, Japanese Festivals, Shrines and Temples, and the Mikimoto Pearl Story “Romance of the Pearl.”12 One of his lectures was held at the local Buddhist temple in Alameda, California.13

One of his connections with the West Coast Japanese was through the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). For example, he went to the second biennial convention of the JACL in Los Angeles in 193214 and his donation of $50 to the JACL convention fund in Seattle in 1936 is on record.15

He also attended the 4th Biennial National Convention of the JACL in Seattle in 193616 as an honorary member.17 It is not known why Tashiro chose to join the Seattle JACL chapter, not the San Francisco one, where one of the most active JACL members was Saburo Kido, an attorney who was born in Hilo, Tashiro’s home island.

A Buddhist at that time, Tashiro strengthened his ties with the West Coast by attending the first All Canada-Hawaii-America Young Buddhist Association Conference held in San Francisco in July 1932, as well as the JACL convention in Los Angeles.18 He participated in those two California conferences with Andy Masayoshi Yamashiro, a Hawai‘i Nisei who was born in Spreckelsville, Maui. Yamashiro was the first Japanese American elected to the Territorial House of Representatives in 1930 and went to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago as a delegate from Hawai‘i in June 1932.19 Although a resident of Chicago, Tashiro represented Hawai‘i at these conferences with Yamashiro.20

In June 1934, as chief representative from North America, Tashiro led a Nisei-only group to attend the Second General Conference of the Pan Pacific Young Buddhist Association, held in Tokyo and Kyoto July 18–25.21 While in Japan, Tashiro observed that “there has been much talk of war with Japan in the United States, but there is little talk of war in Japan. I have found that the Japanese admire the Americans very much.”22

Hosting Japan-Themed Parties

Tashiro also supported an annual student event called National Night at the International House until at least 1938. This was an opportunity for foreign students to share their cultural traditions, history, and customs through entertainment and exhibits.23

The Japanese event at International House was called “A Night in Japan.” On the evening of May 9, 1936, Tashiro held a huge “Japanese Night in Cherry Blossom Time” party with support from the local Japanese community. The Assembly Hall at the House was decorated with cherry blossoms and Japanese lanterns.24 Nearly 600 Japanese and white Americans participated and enjoyed a sukiyaki dinner completely paid for by Tashiro from his own pocket. The event ended with dancing to the music of Erskine Tate’s orchestra.

The party was a huge success, featuring various entertainment programs, including an informational film about Japan made by Tashiro.25 The success of the party was a big boost for Tashiro, who had made immense efforts to support intercultural events and operations in the House.26 Typical of his generosity, Tashiro donated all proceeds from the Cherry Blossom Time party to the International House Student Aids Fund.27

The following year, Tashiro held a “Japan in Wisteria Time” party at International House on April 10, 193728, and brought a huge amount of artificial wisterias and cherry blossoms from Japan to decorate the Assembly Hall for the occasion.29 A sukiyaki dinner party was held in 1938 as well.30 When the Japan America Society of Chicago sponsored an annual dinner party for over 200 American guests at International House, Tashiro was largely responsible for the success of the event in 1940.31

Eventually, Tashiro earned the title of “Japanese philanthropist.”32 The following impression of Tashiro comes from a newspaper column, “From Gang Heaven” written by Tamotsu Murayama, who visited Tashiro in Chicago:

I stayed at International House and Isamu Tashiro took care of me. His activities for improving the US-Japan relationship are amazing. In California we see a lot of Nisei who, once they save some money, try to become part of the so-called “society,” play bridge, and act as if they are not Japanese anymore. Tashiro is a very smart dentist, earning $600 a week, and sacrifices everything to support his larger vision.33

Notes:

1. Hawaii Hochi, July 22, 1930.

2. Author’s correspondence with Wayne Tashiro, September 7, 2022.

3. Daily Maroon, April 21, 1933.

4. Daily Maroon, April 21, 1933.

5. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21, 1935.

6. Ibid.

7. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21, 1935.

8. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, October 10, 1935.

9. Japanese American Courier, November 16, 1935.

10. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21, 1935.

11. Daily Maroon, October 27, 1937.

12. Shinsekai Nichi-Nichi Shimbun, November 6, 1933; Shinsekai Nichi-Nichi Shimbun, November 7, 1933.

13. Nichibei Shimbun, November 5, 1933.

14. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 24, 1932.

15. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, October 6, 1935.

16. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, March 15, 1936.

17. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, March 11, 1936.

18. Nichibei Shimbun, July 24, 1932.

19. Chicago Tribune, June 26, 1932.

20. Nichibei Shimbun, July 24, 1932.

21. Nichibei Shimbun, November 8, 1933; Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, June 18, 1934; Shin-Sekai Nichi Nichi Shimbun, August 18, 1934.

22. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, August 9, 1934.

23. Daily Maroon, December 7, 1938.

24. Daily Maroon, May 7, 1936.

25. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, May 11, 1936; Nichibei Jiho, May 16, 1936.

26. Nichibei Jiho, May 16, 1936.

27. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimun, May 10, 1936.

28. Daily Maroon, April 7, 1937.

29. Daily Maroon, April 7, 1937.

30. Daily Maroon, December 7, 1938.

31. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, May 27, 1940.

32. Chicago Daily Tribune, October 28, 1936.

33. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, July 27, 1936.

© 2023 Takako Day