Archival research is often like gambling; either you get boxes of files that either contain golden information for your project, or a stack of dusty files that make you wonder if you wasted a day of work. And, sometimes, you come across a story you do not expect to find but makes the experience all the more rewarding.

Such is the case with my research on the War Relocation Authority and celebrities. Occasionally, I find stories about famous individuals who, unexpectedly, had a connection to the incarceration of Japanese Americans. Perhaps the most famous cases are those celebrities that were contacted by the War Relocation Authority to help with their publicity campaigns to show Japanese Americans in a positive light.

One of the most noteworthy examples was when the WRA recruited General Joseph Stillwell and then-actor Ronald Reagan to speak at the funeral of 442nd hero Kazuo Masuda in May 1945. In some instances, like Bob Hope’s meeting Japanese American soldiers in Germany, the stories were pure coincidences.

Well, one such story I recently discovered is Frank Sinatra’s encounters with Japanese American resettlers. On two occasions, Sinatra cooperated with the WRA by appearing at events with Japanese Americans to help encourage tolerance from white Americans towards Japanese American resettlers and veterans.

As an artist Frank Sinatra needs no introduction; one of the most famous singers and actors of his generation, his career spanned the 20th century. However, perhaps less known by the public is Sinatra’s long history as an activist. For most of his life, Sinatra was an outspoken supporter of civil rights for black Americans.

During the Civil Rights Movement, he played a key role in desegregating Nevada’s casinos, and in 1961 he performed at a benefit show for Martin Luther King Jr. Before he switched political affiliations to the Republican Party in 1972, Sinatra was an ardent Democrat.

After meeting with Franklin Roosevelt in 1944, he campaigned for various Democratic Presidents, most notably John F. Kennedy. He was a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt - so much so that he invited Roosevelt onto his television show in 1959. Much of his political life has been recorded since in works such as Jon Wiener’s 1986 article, “When Old Blue Eyes Was ‘Red’.”

Some of his most impressive work for civil rights happened during World War II, when his singing career had a meteoric ascent and “Sinatramania” was taking hold. In 1943, following riots in Harlem, Sinatra spoke before several integrated high schools calling for “racial goodwill.”

In 1945, Sinatra starred in The House I Live In, a short film where Sinatra defends a Jewish boy from bullies and pleads for tolerance. The song of the same name became a staple of Sinatra’s repertoire. The lyrics were written by Abel Meeropol, the same author of the lyrics to the song ‘Strange Fruit’ made famous by Billie Holiday, and Earl Robinson, a composer who worked with Paul Robeson on the Ballad for Americans and Joe Hill, wrote the music.

Around the same time, Sinatra made several USO tours in the U.S. and overseas to entertain servicemen. In many cases, these concerts were broadcasted on the radio by the major networks (NBC, CBS) along with Armed Forces Radio Service.

It is in this context that Sinatra had several chance encounters with Japanese Americans. In April 1945, Sinatra travelled to Philadelphia as part of his East Coast tours. There, he was invited by the managers of Fellowship House, an organization founded as a “laboratory in racial and religious understanding” in 1941, to speak about racial tolerance.

As Philadelphia had become a hub for resettlement on the East Coast, several Japanese Americans attended the performance. Living in the top floor apartment of the Fellowship House was the Kaneda family.

Originally incarcerated at Rohwer Concentration Camp in Arkansas, the Kanedas resettled in Philadelphia in 1944. The father, Tsuneyoshi George Kaneda, worked as a cook at the Hotel Whittier, while the mother, Tome Kaneda, cared for their three children: Ruby, a sophomore at Girls High School, Grayce, a secretary at the Family Society of Philadelphia, and Ben Kaneda, a student at Temple University. The Kanedas had four other children living elsewhere: Toshio, a student of music at Yale University; Roy, a postal clerk; Kay a post-graduate student in religious studies at the Presbyterian Assembly School in Richmond; and George, a private in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team fighting in Italy.

Excited to see Sinatra in person, the Kanedas helped with organizing the surprise performance. Grayce Kaneda later gave an account of the evening to the WRA:

The meeting [with Sinatra] was arranged quite secretly through one of the board members, who knows Sinatra’s manager. Over 200 school editors and student council members from 67 public, private, and parochial schools in Philadelphia heard him speak, but only the teachers who accompanied them, our family, and a few others knew beforehand that he would be present. Negroes, Irish, Italian, Chinese, Japanese, Jews, Catholics, and Protestants, etc. were all there together. The surprising element was that Sinatra came to speak on “racial tolerance” rather than to sing as “The Voice.”

Ten cameramen and reporters were at Fellowship House when Sinatra arrived. Some pictures were taken in front of the House, and my brother [Ben] was picked along with a few lucky girls to pose with Sinatra. Later other pictures were taken while Sinatra was speaking, and these included my sister and her friend Irene Tomino. Were they thrilled! My sister and Irene Tomino, who were almost in front of him, were among those who got his much-prized signature.

During his talk, Sinatra told the excited audience that “dis-unity only helps the enemy,” and “most of this intolerance begins with the kids but they get it from their parents, so it’s up to you to be firm with your parents, kids.”

Kaneda’s account of Sinatra was reprinted by the War Relocation Authority’s public relations bureau. The story also appeared in several camp newspapers; the Minidoka Irrigator printed the story under their “Resettlement Report,” and a mention of the event was printed in the Manzanar Free Press.

Sinatra’s kind gestures were feted by the JACL, who thanked Sinatra in the Christmas 1945 issue of the Pacific Citizen. Grayce Kaneda, who later married Hiroshi Uyehara, herself became famous as a redress activist who worked on the JACL’s National Redress Committee and as executive director the JACL’s Legislative Education Committee. (You can learn more about Grayce’s remarkable career here.)

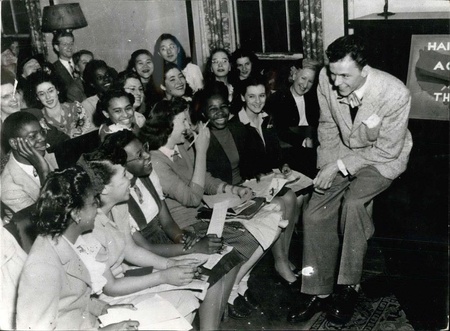

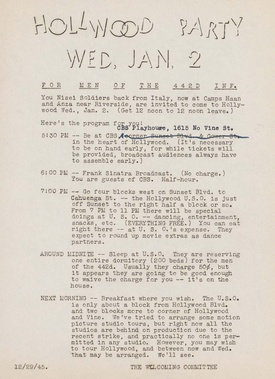

A few months later, on January 3, 1946, Sinatra had another chance encounter with a group of Japanese Americans when he met members of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Los Angeles. Organized by the War Relocation Authority with help from the Japanese American Citizens League, the meet and greet was for 110 Nisei soldiers stationed at Camps Haan and Anza in Riverside who had 24-hour leave passes in Hollywood. Part of Sinatra’s live performance was broadcasted on the radio by CBS Playhouse on Vine Street in Hollywood.

Before the show, Sinatra told the audience of soldiers that “these soldiers with Japanese names – you’ll find some Americans with names like Sinatra too.” He closed his broadcast with these remarks; “to start the New Year right mix in a box of Tolerance – get the big box: it comes in the red, white, and blue package.”

After the performance, the 442nd soldiers mingled with Sinatra and had several photo ops together. The encounter was covered by several Los Angeles papers and circulated by the War Relocation Authority’s public relations office.

Although brief, Sinatra’s story illustrates the dynamic ability of the War Relocation Authority to garner support from cultural figures to help with their campaign of tolerance for Japanese Americans. The WRA – and the JACL - understood the importance of celebrity endorsements towards their campaigns, and Sinatra’s decision to help out in this small but significant way illustrates the fascinating intersection between American cultural icons and Japanese American history. At the same time, it further underscores how the young Sinatra used his stardom to encourage tolerance for Japanese Americans.

© 2024 Jonathan van Harmelen