Back in 2018, I walked the somber halls of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. Prior to my visit, I had read stories and viewed survivors’ interviews, documentaries, and films on the atrocities of the Holocaust. Still, walking through the exhibits with horrific stories and haunting images along with seeing personal items of victims young and old deeply disturbed me. The history of the inhumane treatment and genocide of Jewish people illuminates the darkest side of humanity.

Fittingly the museum’s curators included an exhibit of Japanese people forced into internment camps during World War II under Executive Order 9066. The exhibit includes backlit signs with this Q&A:

Do you think we are doing the right thing in moving Japanese aliens (those who are not citizens) away from the Pacific coast?

Ninety-three percent of a March 1942 public opinion poll by the National Opinion Research Center said YES.

That large percentage is a testament to the power of the media. William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers were among the most influential newspapers in the country and took a stand against Japanese immigration starting in the early 1900s. The paper popularized the idea of the “Yellow Peril,” conveying that Asians were competing with whites for jobs. The bombing of Pearl Harbor added fuel to the bigotry toward Asians.

The climate of anti-Japanese hostility and hysteria, in turn, fostered acceptance of the concentration camps. The Hearst newspapers’ increasingly published anti-Japanese stories, editorial columns, political cartoons, and letters to the editor help cultivate vicious hatred of the Japanese. But the plan to remove and confine the entire population of West Coast Japanese Americans was ultimately a political act.1

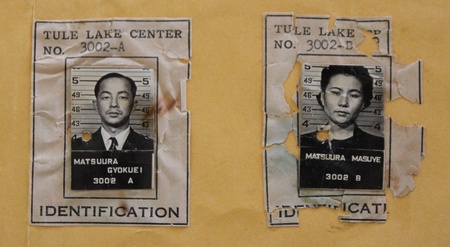

Like the Holocaust, I’ve read stories, viewed video interviews and documentaries of the incarceration of Japanese people. But this story struck closer to home – literally. It traces the journey of Martin Matsuura’s family from the Big Island of Hawai‘i to the Tule Lake internment camp in California. Martin is my Leilehua High School classmate and a former resident of my hometown of Wahiawā.

Family Separation

“My mom packed my dad’s suitcase the day after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. She knew they would come for him, and they did,” said Phoebe Lambeth. Lambeth, a former nurse who retired as chief operating officer of the Hilo Medical Center, is the daughter of Rev. Gyokuei and Masuye Matsuura and the sister of Martin. As a young child she and her mom were separated from her father when federal agents came to arrest him.

Masuye Ota of Wood Valley Ka‘u Homestead was teaching Japanese language at Takara Pāpa‘ikou Gakuen for two years until 1939. During the summer of 1939, she was “matched” by her friend Rev. Zenkai Kokuzo to marry Rev. Matsuura. On Aug. 3, 1939, they were married at Taishoji Soto Mission in Hilo where Rev. Kokuzo presided as minister. Rev. Matsuura was then sent to Kauai Soto Zen Temple Zenshuji to serve as minister.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, they moved to Hilo to help look after the Taishoji Soto Mission with Mrs. Yoshino Kokuzo after Rev. Kokuzo was arrested. In January, Rev. Matsuura was arrested and detained at the Kīlauea Military Camp Detention Center. On March 17, 1942, he was transferred to the Sand Island Detention Center on O‘ahu before being sent to the mainland.

Mrs. Matsuura and Phoebe stayed back at the Taishoji Temple with Mrs. Kokuzo and her young son, Roy. The government asked Mrs. Matsuura if she wanted to go to the mainland to be with her husband and she said yes. But in October 1942, Mrs. Matsuura had major surgery for a ruptured appendix.

“Mom had surgery in Hilo so it took a while before they (government) could move us out, but they were waiting for her to get well, and they were anxiously waiting to take us out. And they stated they were going to send us to the mainland to meet up with my father, which they didn’t do – not right away anyway,” said Phoebe.2

On Christmas Eve 1942, Mrs. Matsuura, 21-month-old Phoebe along with Mrs. Kokuzo and her 4-year-old son Roy were sent to Honolulu. I met with Rev. Roy Kokuzo, a retired Soto Mission minister. He said, “The Red Cross took care of us for our trip from Hilo to Honolulu. We stayed at the Nakamura Hotel across from A‘ala Park in Honolulu. The owner of Nakamura Hotel was a dedicated member of the Soto Mission of Hawaiʽi and he provided assistance to Soto Mission members.”

From Honolulu they were sent to Angel Island in California and then to the Jerome internment camp in Arkansas. The Jerome internment camp had the distinction of receiving over 800 inmates from Hawai‘i, the largest contingent sent to any War Relocation Authority (WRA) camp according to Densho Encyclopedia.

While they were interned at Jerome for over a year, Rev. Matsuura, and Rev. Zenkai Kokuzo were at the all-male Santa Fe, New Mexico internment camp. Mrs. Matsuura was not reunited with her husband as the government had promised.

Sante Fe is where the government held Buddhist or Shinto clergymen, Japanese language school personnel and other leaders of the Japanese community who were classified without evidence by the FBI as “known dangerous Group A suspects.”3

To say the separation from her husband under those circumstances was an emotional hardship would be a gross understatement. “Mom wrote letters to my dad every day, give or take a day or two,” said Phoebe. Mrs. Matsuura wrote in English and Rev. Matsuura, who was not proficient in English, wrote back in Japanese, and there were letters stamped: “Detained Alien Enemy Mail – EXAMINED.”

Mrs. and Rev. Matsuura petitioned the government to put them in a family internment camp so they could be reunited. Here’s the response Mrs. Matsuura received:

The Provost Marshal General had directed that I reply to your letter of 2 July 1943.

It is noted that you and your husband desire family internment in one of the internment camps. As to family internment, the family internment camps are operated by the Department of Justice. It is not known by this office how soon family internment space will be available for families from Hawaiʽi whose husbands and fathers have been interned. This office, however, has called attention to the Department of Justice to the need for family internment in Hawaiian cases and has sent to the Department of Justice a list of cases in which family internment should be brought about as soon as possible. This list includes your husband’s name.

I.B. Summers, Colonel, C.M.P.,

Director, Prisoner of War Division

This letter confirms that the government incarcerated Mrs. Matsuura and her daughter under false pretenses.

The Infamous Loyalty Questionnaire

The ill-conceived “Loyalty Questionnaire” was administered by the US Government to Nikkei citizens and immigrants being held internment camps. It was meant to aid the War Department in recruiting Nisei into the all-Nisei combat unit and assist the WRA to authorize others to be relocated outside of camps. The “loyalty” questions created resentment among Issei and Nisei over their unconstitutional wartime treatment.4

Mrs. Matsuura said, “Why should I sign, why should I support America when you got me, an American citizen, and my daughter in a camp? You did not keep your promise to reunite us with my husband on the mainland.”5

By not signing she was labeled “disloyal”. Because she was deemed disloyal, she and her daughter Phoebe were sent to the Tule Lake internment camp.

Because of the high number of “disloyal” internees Tule Lake was designated a maximum-security “Segregation Center.” More barbed wire was added, and a double “man-proof” fence was constructed. The six guard towers surrounding the site increased to 28, and 1,000 military police with armored cars and tanks were brought in to maintain security.6

It was under these oppressive conditions that the Matsuura family would eventually be reunited.

Shikata Ga Nai

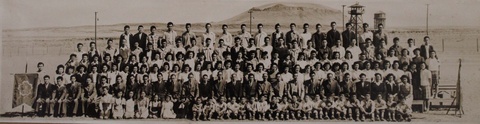

Phoebe said, “my father’s attitude was shikata ga nai – it can’t be helped.” Zen Buddhist priests practiced living in the moment and to focus on the task at hand. And serving others is foundational to their way of life. Phoebe said, “My father was a strong believer in education and started a Japanese school at Tule Lake.”

Rev. Matsuura was principal for the school of 1,200 students until the end of the war. Rev. Kokuzo said parents would shield their children from friction in camp and create a sense of normalcy. Establishing the Japanese school in addition to traditional English schooling was a way for children to focus on learning.

WRA also wanted to instill a sense of normalcy as a diversion from the grim reality and tensions of camp life.7 Sports such as baseball, music, and performing arts like kabuki were encouraged and supported with resources.

Mothers giving birth also casted a light of hope for a bright future for the camp community. Phobe’s brother Thurston was born in camp and so was Rev. Roy Kozuko’s brother Yoshinobu.

Silence on Suicides

Suicides in the Camps: The government downplayed or covered them up when it could. Administrators utilized silence to minimize the ill effects.8

In a Rafu Shimpo article, Sharon Yamato wrote: Although records for incidents of suicide are difficult to find, there is a WRA photo of one man who hanged himself by tying a noose around his neck above a single bed in his small, unkept barracks.

A Drexel University blog stated that on June 4, 1943, less than a year after arriving at Tule Lake, Mrs. Mitsuye Kashi committed suicide. We have no record of why she committed suicide, but one can assume that life in the internment camp was unbearable for her.

A Grinnell College article on health and medicine stated that many internees had such severe depression that they were driven to take their own lives. There was the case of Hideo Murata who killed himself and was found holding his American citizenship certificate.

These internees during World War II were fighting their own battles within their minds.

Returning Home

After returning to Hawai‘i, Rev. Matsuura served at the Daifukuji Soto Mission in Kona as minister. Later he transferred to Kawailoa Soto Mission on O‘ahu and then to the Wahiawā Ryusenji Mission.

Mrs. Matsuura along with her husband helped to build the Wahiawā Ryusenji Mission to what it is today. Mrs. Matsuura spent Saturdays and Sundays going house to house in Kawailoa, Waialua, and Wahiawā asking women to join the Ryusenji Fujinkai (women’s club) to help raise funds. The money she raised helped to purchase two vans for church use. Rev. Matsuura got funding support from community and business leaders who were church members. Together with Mrs. Matsuura’s fujinkai money-making projects they built the temple, residence, Japanese school rooms, and hall, which was later named Matsuura Hall.

Mrs. Matsuura was a woman of conviction who stood her ground on the government’s Loyalty Questionnaire. That strength of conviction showed in her tireless work and dedication to her husband’s mission. Wahiawā Ryusenji Mission is enshrined in both Rev. and Mrs. Matsuura’s legacy.

Rev. Matsuura became the Bishop of Soto Mission Hawai‘i Shoboji in Nu‘uanu where he retired.

Closing Reflections

I asked Phoebe what comes to mind when you reflect on your family’s incarceration? Without pause, Phoebe replied, “I get mad because my mom was so unhappy. She really suffered.”

Media helped to fan the flames of racism against the Japanese people before, during and after World War II. Disturbingly, today there is heightened polarization and racism due in part to misinformation spread on social media.

At the entrance of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum hung a large banner with this message in bold letters: NEVER AGAIN – What You Do Matters.

Notes:

1. Public Broadcasting Service. (2021, September 23). How a public media campaign led to Japanese incarceration during WWII.

2. Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii (JCCH) oral history interview in September 2006.

3. Densho Encyclopedia.

4. Densho Encyclopedia.

5. JCCH oral history interview.

6. Densho Encyclopedia.

7. Densho Encyclopedia.

8. Excerpted from southernspaces.org.

© 2024 Daniel Nakasone