Morimasa Kaneshiro was born and raised in Hilo where his family ran a barbershop. After graduating from Hilo High School in 1944 Kaneshiro volunteered for the Army. He was stationed at Schofield Barracks on Oʽahu after completing his infantry basic training on the mainland.

He did not attend the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS), but he developed Japanese language skills while growing up with Japanese speaking parents. Because of those skills he was assigned as an interpreter to the U.S. Navy. His unit was given orders to serve in Okinawa in a humanitarian capacity. Kaneshiro assisted medical officers in carrying conversations with Japanese patients. He also served in the “Mop Up” phase of the battle helping to call out civilians and Japanese soldiers hiding in caves.

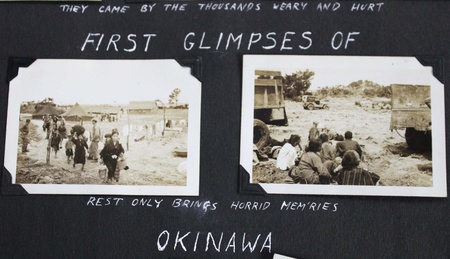

First Glimpses of Okinawa

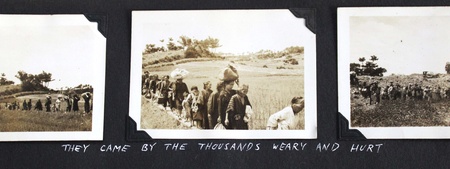

“They came by the thousands weary and hurt. Rest only brings horrid memories.” These were the haunting captions 19-year-old Morimasa Kaneshiro’s wrote on a page with his photos titled “First Glimpses of Okinawa.”

The caption on the bottom of the page from his photo scrapbook read:

Evacuation of natives from the front - May 17, 1945. That’s over a month before the battle ended. The actual number is not known but the line of people stretched into the distance. The elderly people and young women and children who walked single file into the camp were the fortunate ones.

According to the caption they were spared from the oncoming ground battle and the death and destruction it would leave in its wake. The evacuation essentially saved many of their lives because of Kaneshiro and his fellow soldiers.

The core mission of his unit was to provide the initial humanitarian needs of food, medical supplies and care, clothing, housing, and police protection for the civilian population. Their story is significant for it tells the side of providing aid and saving lives not taking them.

Like the vast majority of interpreters who served during WWII Kaneshiro remained silent about his good deeds amidst the trauma and devastation. Kaneshiro’s photo scrapbook with captions captures just a small portion of his war time experience. There is more to his story that only oral history can reveal.

Finding Morimasa Kaneshiro

Kaneshiro took part in saving many lives but there was one life that he personally saved that shined a light on his story.

I stumbled on that story while working on a video documentary on my family’s Battle of Okinawa story. Yoshino Nakasone, my father’s younger sister was born in Hawaiʽi but living in Okinawa with their grandparents during the battle. She survived the relentless bombing by hiding in a cave with her grandparents and a few others from their village.

While interviewing her daughter Alice for the video documentary, she mentioned that a Nisei soldier named Kaneshiro from the Big Island had called her out of the cave. Alice said Kaneshiro told her mom his name and that they were going to take care of her and the others.

I believe he shared his name to let Aunty Yoshino know that he was a fellow Okinawan to build trust. It’s extremely rare to make the connection between a Nisei soldier and a person he called out of a cave. And both being from Hawaiʽi is unheard of. I was stunned!

It is well documented that Japanese Imperial soldiers had spread propaganda that women would be raped, tortured, and killed if captured by American troops. Alice said, “the plan was that my mom’s grandparents would come out of the cave, and she would stay behind.”

When Americans exhausted all attempts to call out people, they would either apply flamethrowers to the cave or ignite explosives to seal its entrance. Yoshino’s grandmother told the Americans that her granddaughter was still in the cave. Kaneshiro calling her out literally saved her life.

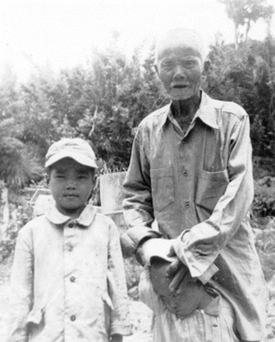

What makes Kaneshiro’s story even more remarkable is that he also called out his paternal grandfather and young cousin also named Morimasa Kaneshiro from another cave.

Because of Kaneshiro my Aunty Yoshino was able to return to her family in Wahiawā, Hawaiʽi. She would marry a wonderful man Robert Toguchi from Pepeʽekeo on the Big Island and together they raised five children.

I had to find Morimasa Kaneshiro. Not trying was not an option. I reached out to Karleen Chinen, former editor of the Hawaiʽi Herald and she contacted her friend Drusilla Tanaka who sourced Seiki Oshiro’s research on Nisei MIS soldiers. In an email Tanaka identified four Kaneshiro MIS soldiers who served in Okinawa and only one from the Big Island, Morimasa. After a few calls, my Cousin Norman Nakasone former president of the Hawaiʽi United Okinawan Association led me to Charles Kaneshiro, Morimasa’s eldest son. (Although Morimasa Kaneshiro did not attend MILS he is listed on the MIS roster.)

Charles said when his late father fell ill with Parkinson’s he started to share his Battle of Okinawa stories with his family. One of the stories his dad shared was that he found his “calling” because of his life changing experience in Okinawa.

“My dad had an ambition to become an engineer, but he decided to pursue a life as a social worker instead. Through the ‘G.I. Bill’ he and a friend attended Drury College in Springfield, Missouri where he got a degree in social work. And through a referral he attended Seabury Western Theological Seminary,” said Charles.

Rev. Kaneshiro began his ministry by serving in various churches in Kohala, Honolulu, Kauai before becoming chaplain of the lower school of ʽIolani School where he was affectionately known as “Father K.”

Rev. Kaneshiro was a true Uchinanchu who loved to play ukulele and sanshin and singing with his karaoke group. And although his wife Myrtle is not Okinawan, she is Uchinanchu at heart. She was a member of the Okinawan women’s organization Hui o Laulima for nearly 40 years and served as its president from 1990 to 1992. Together they raised three sons and a daughter.

Sadly, Rev. Kaneshiro passed on in 2009 due to his illness.

A Story that Binds Two Families

Knowing that the Kaneshiro and Toguchi families shared an extraordinary connection I felt the two families should meet face-to-face. Both families agreed. The expression of warmth and gratitude by all that day was palpable. But on a deeper level, family members on both sides understood the profound circumstance that brought them together.

“It was overwhelming. I’ve never read any stories that identified an MIS soldier and a person he called out of cave. And to have both from Hawaiʽi is so significant.”

— Mrs. Mrytle Kaneshiro

“It’s humanizing. To meet the family members of someone my dad called out of a cave was life changing.”

— Charles Kaneshiro (Sansei)

“The warm and inviting Kaneshiro family was a reflection of the kind of man Mr. Morimasa Kaneshiro was. All the information we learned made me realize that because Mr. Kaneshiro was such a kind and compassionate person and being Okinawan American, my mom and her grandparents felt safe.”

— Elaine Toguchi Chun (Sansei)

“We would have never imagined that we would meet the family of the man who saved my mother’s life. What happened was nothing short of a miracle.”

— Alice Toguchi Matsuo (Sansei)

“I can’t help but wonder if they would have come out of the cave if it had been someone else. I imagine it was his demeanor and compassion that led my grandma and her relatives to trust him.”

— Carianne Matsuo (Yonsei)

“From everything I learned through this journey, I feel closer to Grandma Toguchi than I ever have. To uncover the missing pieces of the Nakasone Family story helped me develop a stronger sense of our family history and understand how much the early generations endured and persevered. I am proud to be an Uchinanchu!”

— Kristen Toguchi Ishii (Yonsei)

Closing Reflection

Countless stories like Kaneshiro’s are lost for eternity for one reason or another. MIS Soldiers having sworn to secrecy, enryo the Japanese manner of restraint, or not wanting to relive the horror of war are reasons they remained silent. Although later in life there are few who would share their stories and others only when asked. My late dad Seiei Nakasone served in the Military Intelligence Service, and he kept his stories to himself. Until this day I regret not asking him questions while I had the chance.

It’s been over 78 years since WWII ended. Finding Morimasa Kaneshiro’s Battle of Okinawa story and his connection to my family’s story is like finding the proverbial needle in a haystack. I would venture to say that divine intervention may have had a hand in it.

The hope is that future generations of the Kaneshiro and Toguchi families will learn the story of that faithful day when Morimasa saved Yoshino.

*This article was originally published in Uchinanchu: The Voice of the Hawaii United Okinawa Association on December 21, 2023.

© 2023 Daniel Nakasone