“I was a very shy child,” he confesses, preferring to be at the back of the group during sanshin presentations. That’s how John remembers his beginnings as an artist in Peru. The son of Yochan Azama, a well-known Nikkei singer in Peru, he has innate musical talent.

John Azama is Yonsei, born in Peru, and for the past seven years he has lived in Texas, where he has a family and works in information technology at an airline. But passion for music continues to resonate with him, these days through the eisa drums. Since 2018, John has been the director of Ryukyu Damashii, an up-and-coming eisa group from Dallas-Fort Worth.

Artistic Beginnings in Peru

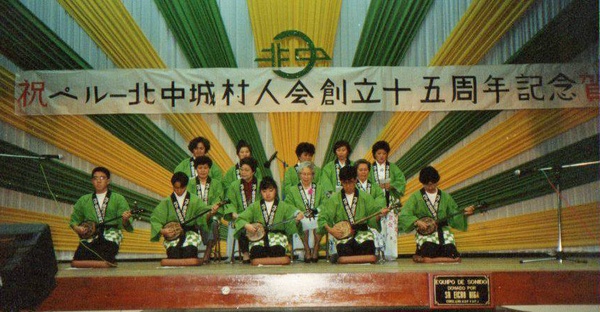

Even today, John stays closely connected to his Kita Nakagusuku sonjinkai, which started in 1995 when he accompanied his father to practice. He began by playing sanshin and later danced as well.

John was a member of the Haisai Uchina sanshin for several years starting in 1996 as well as Matsuri Daiko, the only official eisa group in Peru. Both groups performed mostly at the festival organized by Asociación Estadio La Unión (La Union Stadium Association), where John played the sanshin first and then returned to the stage to dance eisa. “At the time, I didn’t have the courage to sing. I was really shy,” he says.

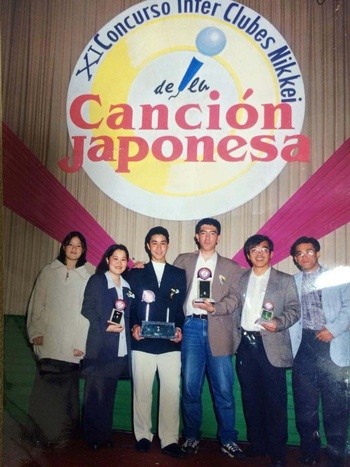

His debut as a singer came in 1997, when he participated in the Interclubes de la Canción Japonesa (Japanese Interclub Singing) competition. He qualified for the New Voices category initally and continued to participate after becoming well-known.

Since then, John has sung ballads, rock, and even J-pop with the group Hayabiki, where he was the lead singer.

His talent didn’t go unnoticed and he was asked to join Akisamiyo, a musical group created especially for the celebration of the 110th anniversary of Okinawan immigration to Peru.

New Beginning in Dallas

In 2017, John moved to Dallas for work, and one of the things he missed most about Peru were the activities in the Nikkei community. He was so nostalgic that he traveled to Peru just to participate in community events, taking advantage of the travel benefits he received as an airline employee.

Once he landed in Dallas, John set out to find a group of Okinawans. At first he found a women’s odori group, but after a year, he met the member of an eisa group. That happened after a flight where a Japanese flight attendant who also lived in Dallas told him about a tanomoshi group that included a woman who was a member of eisa group Ryukyu Damashii.

“Soul of Ryukyu”

Ryukyu Damashii, which means “Soul of Ryukyu” in Japanese, was founded in 2015 by Yukimi Iha and Ritsuko Shibayama. Their goal was to create a space for gathering and disseminating Okinawan culture through eisa.

The group, with fewer than 10 members initially and mostly made up of women over the age of 60, learned eisa through instructional videos. They met to practice at the house belonging to the odori sensei of the Dallas Okinawan Association.

John first encountered Ryukyu Damashii in 2018 and quickly became part of the group. He already knew two of the three dances they practiced. He suggested some changes in the choreography and accompanied the group to a performance. Since then, he has been the designated instructor for Ryukyu Damashii.

Today, Ryukyu Damashii’s members consist mostly of women from Okinawa. Some have American husbands, and there are two members who are not of Japanese heritage. Over time, some members have left the group because they’ve moved to other cities or returned to Okinawa. But now there are Niseis and two young women have joined the group.

The Challenges of a Dance Instructor

“Directing a group of obachan (a casual way to refer to middle-aged/senior women) has been an interesting challenge,” he says. “Not only do I teach choreography and find new songs, but I also have to adapt the steps or create new ones especially for the dancers.” Since most of the dancers are over 50 years old, he explains, “Not everyone can do jumps, quick turns, knee bends, or fast spins.”

Another challenge was earning the group’s trust. “If there is a step that doesn’t work, please let me know!” he told them, after finding out that a member was planning to leave the group without saying anything because she wasn’t able to master a dance step.

John explains, “The purpose of Ryukyu Damashii is not to be a professional eisa school, but a group that brings together people who love dancing and Okinawan culture.”

John also mentions that the group is currently renting a space at the community center in the city of Euless, so they have to pay every time they practice. But despite the obstacles, they do it “for love of the art.”

Can Seniors Transmit the Same Energy with Limited Mobility?

“Everything depends on the dances,” says John, adding that there are dances that require energy and a lot of heishi, which are the energetic shouts, like iasasa or sui sui sui.

To transmit that energy in every performance, John starts the heishi and conveys that excitement to the group, standing on the stage so that everyone in the group can see him as he guides them through the steps. Good energy and joy can be transmitted through dance, he explains, and that’s true even for the most serious song, called “Miruku Munari.”

Despite the limitations, John always tells the group: “The important thing is to have fun!”

In the beginning, the group’s dances were fairly simple and didn’t have much impact, he says. He decided to create some variations including interacting more with the audience, live singing, heishi, and the typical Okinawan yubibue finger whistle.

The group’s performance has benefited from John’s arrival, as evidenced by the positive responses of audiences.

The Nikkei Community in Dallas and Lima

Whether in Dallas or Lima, Okinawan hospitality and kimochi is always the same, as John tells it. “The obachan, for example, are the ones who always encourage you to eat what they have prepared, just like the obachan in Peru.”

The difference with Peru is that the Nikkei community in Dallas is small, organizes only a few activities, and does not have its own local group like the Okinawan Association in Peru, he explains.

“Although there are Nikkei institutions and leadership in Dallas,” he adds, “there is no place where Nikkeis can gather. Instead, there are spaces that people rent or we borrow someone’s house. We’re more like a group of friends who like to get together, rather than a strong community.”

Another difference John has noticed is the more active participation of seniors in the eisa and odori groups and the kenjinkai activities, unlike the groups in Lima, which are mostly made up of young people.

John attributes the greater interest among younger Peruvian and Latin American Nikkeis in community activities to their strong connection to family and roots. This connection is perceived as less intense in the United States, he explains, where young Nikkeis tend to become independent from their families at an earlier age and grow up with less exposure to Japanese culture, expecially Okinawan culture.

He also believes this interest may be stimulated by scholarships to study in Japan or Okinawa. “The students who go to Okinawa generally come from Brazil, Argentina, and Peru and when they return to their countries, they have been saturated by the culture and energy needed to participate in activities.” While there are scholarships for students in the United States, John says there isn’t much interest in applying for the scholarships to travel to Okinawa.

“But if the lack of young people’s participation is due to the lack of physical spaces, this would be like asking ourselves, which came first, the chicken or the egg?”

Eisa and Singing

John is the only member of the group with experience in stage management and event coordination, so he introduces the group and entertains the audience during intermissions, while the dancers are changing costumes. At those moments, John talks about Okinawan culture or sings live.

Here’s an anecdote about that: The first time he sang at a performance, he hadn’t foreseen that the eisa movements would leave him breathless when it came time to sing. “I was almost out of air!” he says.

John has integrated singing into the eisa performances and at one time considered including sanshin, but that hasn’t happened yet. During some past performances, John talked about sanshin and played a few songs, but not any longer. “Setting up the microphones, playing and then putting on the taiko to dance required a lot of logistics, and our time was limited. It became more stressful than fun,” he says.

But John isn’t about to stop. He would like to include live music in the performances, even though he hasn’t yet found anyone willing to sing on stage.

Connecting to people in Dallas who are interested in Japanese music like the kind he used to sing when he lived in Peru, “would be fantastic,” he says.

But bringing together a group of singers in Dallas at the association level, similar to the work of the Asociación de Cantantes Nikkei (Association of Nikkei Singers) in Peru, requires free time and involves a lot of responsibility.

John has a few projects in mind, but the lack of time is the main obstacle.

Eisa and Country Music

This interesting proposal has been pending since last year: combining eisa with country music, which is a popular genre in Texas. John would like to do it and has the energy, but lacks the time, he says. After work, he dedicates the rest of his day to his son Raiden.

But in addition to being the group’s instructor, John is also in charge of Ryukyu Damashii’s social media presence. He maintains the group’s accounts on Instagram and Facebook, where he promotes the performances and asks people to share photos and tag them.

Connecting with Okinawan Culture Through Music

Music is the link that connects John to his Okinawan roots and even though in the beginning he didn’t find opportunities to sing in Dallas, he discovered that he could express himself through eisa.

“Eisa is a way to connect myself to kenjinkai, the Okinawan collective in Dallas.” Through the eisa performances, John found opportunities to meet people from different places and integrate singing, one of his lifelong passions.

Collaborations between Uchinaanchu1 Singers

John’s connection to music is so strong that it led him to participate in “Sanshin nu Takara” (The Sanshin Treasure) in 2021, a collaborative cover with the Argentinian Dany Hokama, in celebration of World Uchinaanchu Day.

The song is inspired by two songs, “Katateni Sanshin wo” by the group Diamantes and “Shimanchu nu Takara” by Begin. The song features famous Nikkei artists of Okinawan origin, such as Kaley Kinjo (Canada), Brandon Ing (Hawaii), Gus Hokama (Argentina), and naturally, John Azama (Peru). Not only did John sing, but he also contributed the yubibue whistles and the heishi shouts that are so characteristic of Okinawan music.

The next year, in 2022, John was invited to participate in “Syuri no Uta” (Song of Shuri), the purpose of which was to raise funds for the reconstruction of Shuri Castle, the Okinawan symbol that was devastated by a fire in 2019. The song project was organized by the Okinawa Prefecture and recorded in four languages (English, Chinese, Portuguese, and Spanish), with John singing the English version.

Infecting his Son with the “Eisa” Soul

John’s major music influence was his father Yochan Azama and it appears that his son Raiden, who will be two years old in March of this year, is following in his footsteps. John jokes that he is more than interested in music; Raiden appears to be obsessed.

“Every morning Raiden asks me to put on music, and in any situation, he always says words that allude to eisa. For example, he loves to say “iasasa aia” and when he’s annoyed he repeats “taku bachi,” which comes from “taiko” (drum) and “bachi” (drumstick).

John thinks his son might be using taku bachi in the same way that we use the popular expression “Chamare!” in Peru. For example, when we say: “This didn’t work well…chamare!” Raiden’s obsession with eisa started when he received a taiko as a gift from a friend in the eisa group.

While he doesn’t expect to find the level of enthusiasm for eisa that is seen among Nikkei youth in South America, John would at least like to increase local interest and add a little more spectacle to the eisa performances in Dallas.

John believes that eisa could be a way to attract young people and increase their interest in Okinawan culture. He says “the sound of the drumbeat always has an impact and resonates in everyone’s hearts."

Note:

1. Uchinaanchu: Okinawans and their descendants, in the Uchinaaguchi language of Okinawa.

*Ryukyu Damashii: Facebook | Instagram (@ryukyudamashiidfw)

* * * * *

Saturday, March 9, 2024 • 3 p.m. PST (ZOOM)

Join us for a conversation and Q&A with members of contemporary eisa groups—Lisa Tamashiro Maumalanga (Chinagu Eisa Hawaii), Rentaro Suzuki (Ryukyukoku Matsuri Daiko Los Angeles Branch), John Azama (Ryukyu Damashii), Cecilia Nué (Seiryu Eisa Kai), and Toshiyuki Yamauchi (Yuriki no Kizuna Eisá Daiko)—as they discuss how eisa connects them to their cultural heritage and identity. An interactive beginners tutorial and opportunity to talk with members from various eisa groups will follow the program.

The main program will be presented via Zoom, with simultaneous translation in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Registration is required.

© 2024 Milagros Tsukayama Shinzato