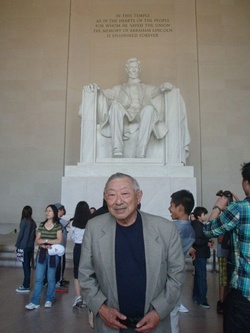

For my father, Nisei playwright, poet, and actor Hiroshi Kashiwagi, the journey up the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in the heart of Washington, D.C. was steep and arduous. Now 88-years-old, he moves much slower than he used to, but he was determined to reach the top, slowly, step by step.

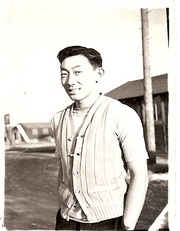

Because for my dad, a steep climb up some steps is nothing in comparison to the long journey he has taken throughout his life to reach this moment. From a small, country store in Loomis, California to behind barbed wires at the Tule Lake Segregation Center during WWII, his road to Washington has not been easy.

Branded and stigmatized as “disloyal” and a “troublemaker” by members of his own community for his refusal to answer two deeply flawed U.S. Government-imposed “loyalty” questions, he has lived a shadowy life of a “No-No Boy,” once considered the “lowest of the low” among those Americans of Japanese ancestry who protested their unjust WWII incarceration in America’s concentration camps.

The heroes, so says the Japanese American historical narrative, were and are those who served valiantly in the 100th Battalion, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). And there’s no doubt that they are heroes indeed, with numerous achievements, casualties, and the Congressional Gold Medal to prove it.

However, for those who stood up for their civil rights and protested their unconstitutional treatment—people like the No-No Boys of Tule Lake, the Heart Mountain Draft Resisters, and the 1800th Military Battalion—the JA historical narrative has been much less kind. In fact, the story of Japanese American dissent has long been ignored, dismissed, or denigrated by some members and organizations within our community, so much so that the vast majority of the dissenters were driven into a lifetime of shame and silence.

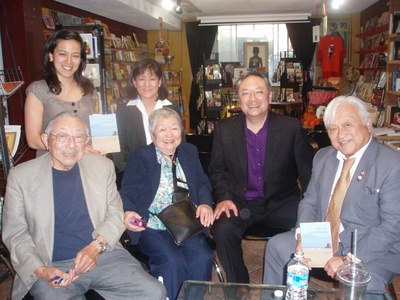

The West Wing Entrance includes Anne Francis (front), Nina Fallenbaum (back), me, and my parents, Sadako and Hiroshi Kashiwagi.

It is within this historical context that my dad, through a miraculous combination of an African American President in office and a Hapa Yonsei named Nina Kahori Fallenbaum, received an official invitation to “An Evening of Poetry & Prose,” from President Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama which was held on Wednesday, May 11 in the East Wing of the White House.

Fallenbaum knows my dad from hearing him read his poetry about Tule Lake at the Tule Lake Pilgrimages. She has served for several years on the Pilgrimage planning committee, and when she moved to Washington, D.C. two years ago she took her activism to tell the Tule Lake story with her. She soon became friends with several Asian Pacific American staffers in various political offices. One of her friends is Bryan Jung, who works in the White House Office of Community Engagement. She passed my dad’s book of poetry on to Bryan, and the next thing they knew, my parents received a call from the White House.

My mom and dad, the Tule Lake “No-No Boy,” were going to Washington to attend the event, and they would get to shake the hand of the President of the United States and the First Lady at a celebration of American poetry.

Book Reading at an African American Bookstore

The evening prior to the White House poetry event Nina Fallenbaum organized an intimate book and poetry reading at Sankofa Bookstore near Howard University in Washington, D.C. The store, started by African American filmmakers, features an array of African American literature, films, children’s books, and a café. Nina spoke to the owner about my dad’s story, and after five minutes she was convinced that she wanted him to read at her store.

Attended by several of Nina’s API friends who work in Washington along with a handful of Japanese Americans, Japanese Nationals, African Americans, an African National, and Caucasians, the event was like a throw-back to the 1970s where poets and writers would often read their work in intimate bookstore/coffee house settings.

My dad began by saying he and other Japanese Americans grew up in America with racism always present. He then provided an historical context and overview of what happened to 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. He said he enjoyed the new adventure that was camp at first, but in February 1943 all that changed with the advent of the infamous “loyalty questions.” Then he started reading his poems that spoke to the pain of Tule Lake. In between poems and stories, he took questions from the audience, many of which were about his experience as a “No-No Boy.”

“I always thought I was an American,” he said. “But when they questioned our loyalty, I was confused. I began to doubt that I was an American citizen, even though I had absolutely no allegiance to Japan.”

Asked about the after effects being a “No-No” had on his life, he spoke of not having a social life among other Nisei for fear that his “No-No” past would come back to haunt him in the form of subtle or not so subtle rejection and ostracism. In his poetry and in the pages of his memoir, the pain of this experience is expressed. But he has never wavered from his stand that what the U.S. Government did to Americans of Japanese ancestry was wrong, and that it had no right to question his loyalty to the U.S. that was always there from the beginning.

“Do you have anger or resent toward the U.S. Government for what happened to you,” he was asked. He paused and thought about this for awhile. “I don’t have any anger or resentment toward the government. Having that would go against everything I’ve stood for in my life.”

He added that the apology and redress from the U.S. Government took the burden of shame off of our community, and helped enormously in the healing process.

Then he was asked how he felt about being invited to the White House by the President and First Lady.

“Being here, I can say that I’m proud to be an American,” he said. “There was a time when I couldn’t listen to our National Anthem. But now when I hear it, I feel that it’s my song, too.”

At the end of the reading, the owner of the bookstore, an African American woman named Shirikiana, said she had a couple things she wanted to say to my dad.

“First of all, has anyone ever thanked you for the courage it took to be a “No-No Boy?” she asked. When my dad hesitated and said, “Not directly.” She then said, “Well, we can take care of that right now.” Everyone yelled out “THANK YOU!” and started to applaud. She then continued. “You are my elder. But you are not only my elder, you are one of our nation’s elders. And if you don’t mind, I would like to do something right now.”

She reached behind my dad’s back and removed an imaginary burden off of his shoulders, and placed it “where it belongs in a courageous heart,” she said.

That day, my dad made it to the top of the Lincoln Memorial. And as we stood under the words of the Emancipation Proclamation and looked out on the National Mall, I could not help but think of Dr. Martin Luther King and his “I Have a Dream Speech.” I remembered those famous words, and how they applied to my father at this moment:

“Free At Last, Free At Last!” He is Free At Last.

© 2011 Soji Kashiwagi